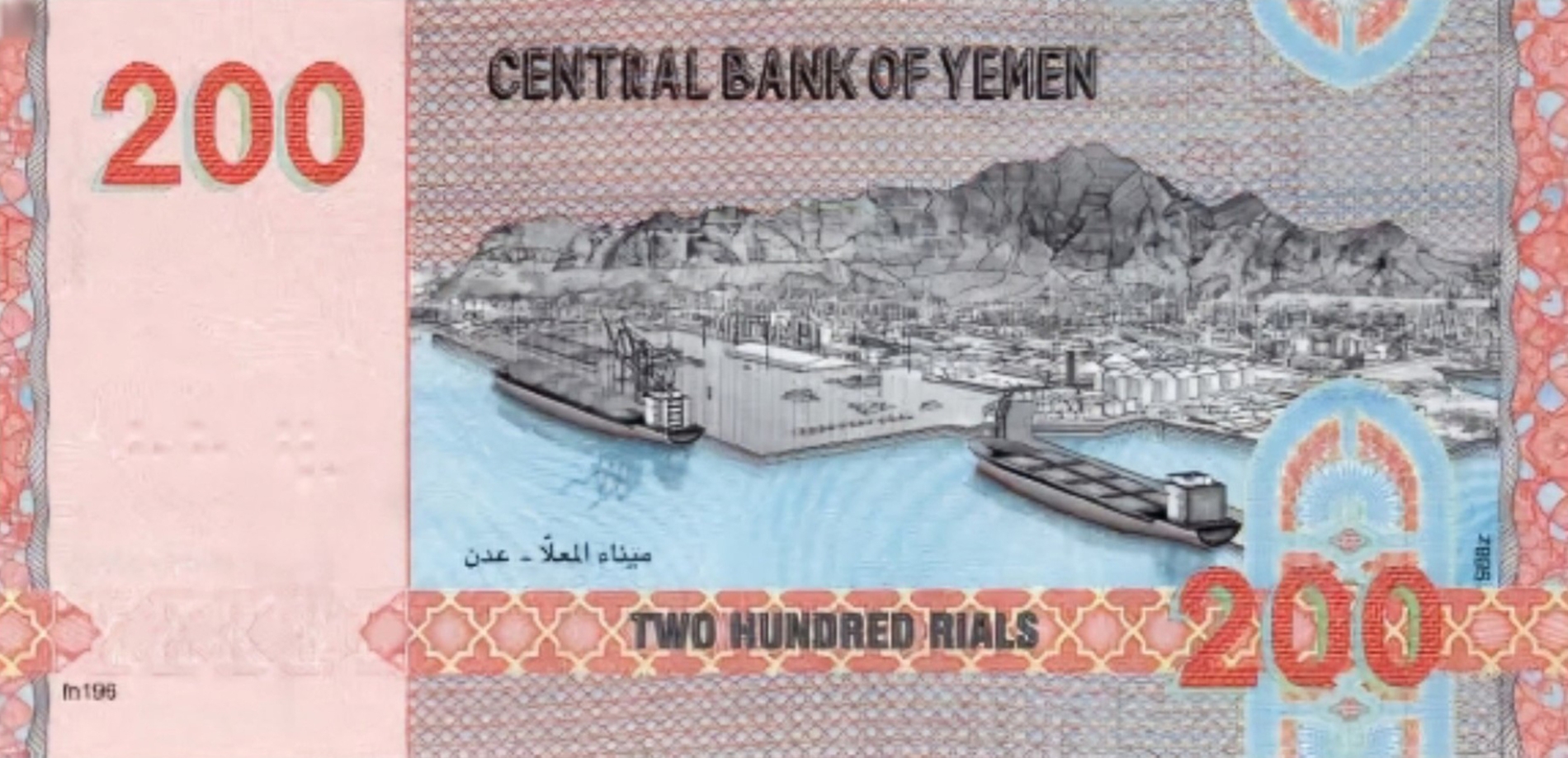

Barely a day goes by without Yemen’s Houthi group being in the news. Earlier this month, it attacked and sank two sea-going vessels. Then a naval interception revealed military and communications equipment bound for Houthi-controlled ports. Then, on 16 July, the militia unveiled a newly printed 200-rial banknote—meant to replace the older 250-rial denomination—which they began circulating in areas under their control, including the capital, Sanaa. Days earlier, the group issued a new 50-rial coin.

On the surface, the new notes seem sensible and necessary to replace vast quantities of deteriorated or worn-out bills, but the Houthis ensured that this purely technical act carried a far heavier political payload. The group is designated as a “foreign terrorist organisation” by the United States and several European countries, meaning that it is subject to a series of economic sanctions imposed by the US Treasury Department.

Two days before the Houthis released their newly printed-and-minted denominations, the Yemeni Central Bank—headquartered in the southern city of Aden, which is not under Houthi control—denounced the move as a “destructive and reckless act issued by an illegal entity,” adding that it was “a continuation of the economic warfare waged by the group to plunder the people’s resources and savings in order to fund its shadow networks with massive sums, absent any legal or monetary oversight”.

Economic fragmentation

The UN Special Envoy for Yemen, Hans Grundberg, described the Houthi initiative as a “unilateral measure,” arguing that it would not solve Yemen’s liquidity problems and could further destabilise the country’s already fragile economy and deepen the division of its monetary and institutional structures. It further contravenes the understandings reached on 23 July 2024 between the warring parties concerning economic de-escalation, he said, calling for a “coordinated approach that encourages dialogue, supports wider stability efforts, and seeks pragmatic solutions that benefit all Yemenis”.