Philosophising through cinema can be done in one of two ways. Philosophical thought can either be reinterpreted through film, or else filmmakers can engage in their own original philosophical inquiry through the medium. It may sound odd to think of cinema as philosophising, but consider some of the finest science-fiction films if in doubt. Blade Runner was not merely a cinematic adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? It was a profound encounter between philosophical imagination and the cinematic lens.

Directed by Ridley Scott and released in 1982 shortly after Dick’s death, the film vividly animates the author’s central concerns: the unreliability of reality, the disintegration of identity, and the erosion of meaning. Yet most striking is the slow inversion of roles.

Replicants begin to exhibit human traits, while humans behave with mechanical detachment. At the core of this paradox is Deckard, the emotionally numb bounty hunter, and Roy Batty, the artificial being who acquires a soul. Ultimately, the machine teaches the human what it means to be human.

Truth and falsehood

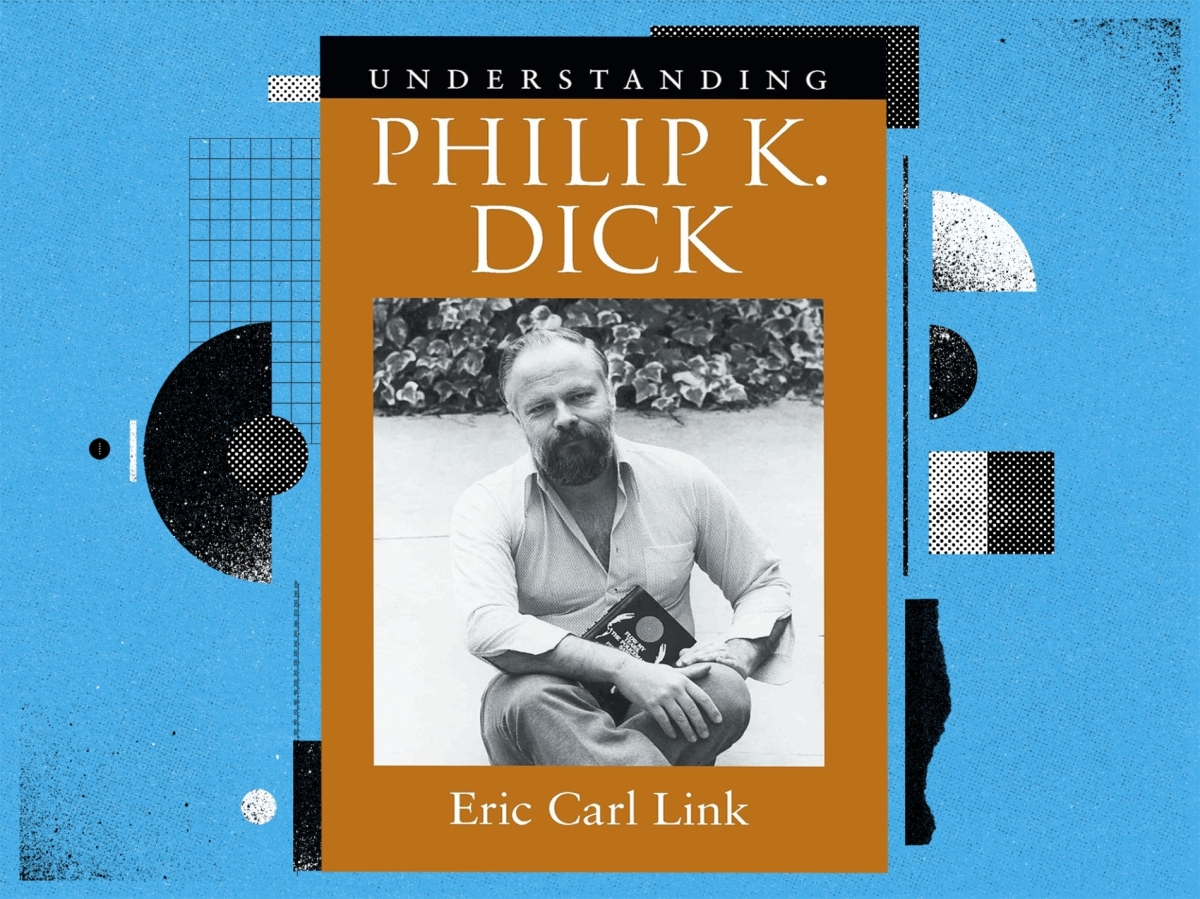

Philip K. Dick was far from a conventional sci-fi writer. He revealed false realities and posed unsettling questions. How do we know that what we perceive is real? Could our memories be fabricated? Are we truly who we believe we are? In his fiction, sensory experiences collapse, and truth reveals itself as a succession of layered illusions.

In Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, he was less interested in painting a futuristic world than in unmasking the fragility of our existing reality. The novel’s title alludes to its central philosophical question. The sheep are not just animals; they are symbols of innocence and compassion.

For Dick, humanity’s true hallmark was not intellect but empathy, so the test of what makes someone human lies not in intelligence but in sorrow—the capacity to feel for another. In Blade Runner, this idea takes form in Rachael and Roy, replicants who serve as moral consciences within the world.

In stark contrast, the protagonist Deckard begins as a mechanised instrument of execution. With bitter irony, he moves like a machine, showing no hesitation, doubt, or remorse, despite possessing a collection of photographic memories. Assigned to "retire" the replicants, he does so without ethical reflection.