Across the Arab world, and particularly in Egypt, food security is increasingly moving up the political agenda, as inflation, geopolitical conflicts, trade tensions, and tariffs have led to recent turbulence in food prices.

According to the World Food Programme, 10% of the world’s population (about 770 million people) now face serious risks due to under-nourishment, with climate change reducing crop yields and shrinking the areas under cultivation.

While some countries are bolstering their strategic food reserves, others are grappling with acute shortages caused by a lack of supply and a lack of affordability. With the war in Ukraine and conflicts in the Middle East rumbling on, governments are striving for self-sufficiency amidst growing pressures.

Inflationary pressures stem in part from tariffs placed by returning US President Donald Trump, but war and geopolitical tensions have also negatively impacted the stability of food prices in the Arab world. This is especially true during Ramadan, when demand for some foodstuffs surges.

Despite several major players in the Arab food sector, prices are adversely affected by crises, instability, and meteorological conditions, such as drought. Egypt is currently experiencing water scarcity amidst its dispute with Ethiopia and is having to import many agricultural crops to meet the demands of a swelling population.

Meeting domestic demand

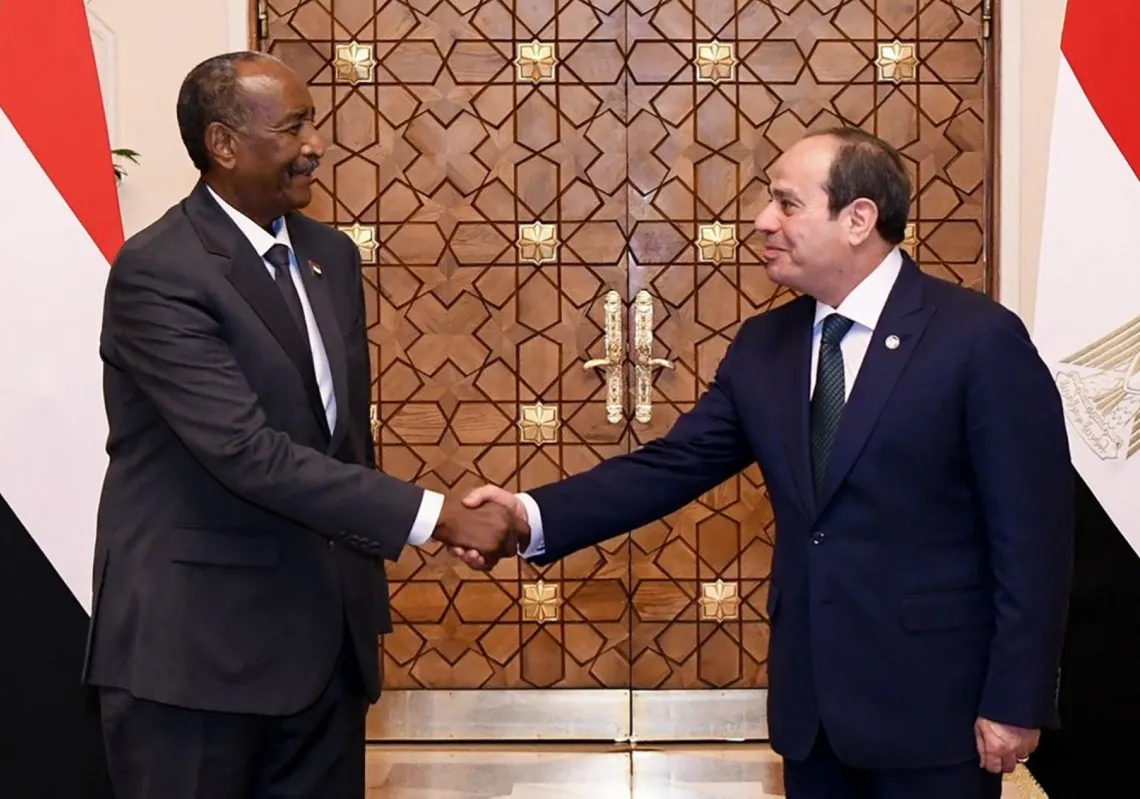

Like many other countries in the Middle East, Egypt currently hosts many refugees, which has exacerbated the issue of supply and demand. In previous years, Egypt relied on crops from northern Sudan, including wheat, but civil war there and rising tensions with Ethiopia have put an end to this approach.

Egypt consumes 12-16 million tonnes of wheat annually but produces only around 9 million tonnes. Imports bridge the gap. It wants to produce more, though, and Cairo recently reached an agreement with the United Arab Emirates to reclaim land in Egypt’s Toshka Lakes region for wheat cultivation.

Cairo wants to boost domestic production of strategic crops to reduce the import bill and enhance exports to support its dollar reserves. It currently cultivates around 10 million acres but wants to increase this to 11 million by 2026-27. Incentivising farmers, one aim is to increase wheat self-sufficiency to 53% from 49% at present.

Syria once supplied the Arab world with many agricultural products and crops, but civil war and a population drain put a stop to that. In the Gulf, Saudi Arabia has emerged as a key player in the agricultural sector, developing its livestock and poultry industries for self-sufficiency, and exporting any surplus.

Agricultural collaboration

Some economists and agricultural experts believe that Arab solidarity is needed to achieve self-sufficiency. Many rely on the import of wheat, not least from Ukraine and Russia, while many Gulf states get their wheat from the United States.

Some Arab economic experts call for the creation of a joint Arab market, given states' geographic proximity, common language, and combined economic and human resources, which can be better leveraged through wider regional cooperation.

Sudan has enormous agricultural resources, supplying (in good times) large quantities of meat and grain to the Arab world. Others, like Morocco and Jordan, excel in areas like sesame cultivation and olive oil production. Better Arab food cooperation could lead to enhanced food security, lower prices, and lower inflation.

With divergent stances, food insecurity persists. Rich states can feed their populations, while poorer states rely on borrowing, adding to fiscal deficits. In Sudan, the situation is so bad that accessing food has become critical for much of the remaining population.

In Tunisia, adverse effects from drought and climate change have had an effect on food supplies and prompted a drive to achieve self-sufficiency. Like Egypt, Tunisia has also turned to food imports and been hit by the repercussions of war in Ukraine.