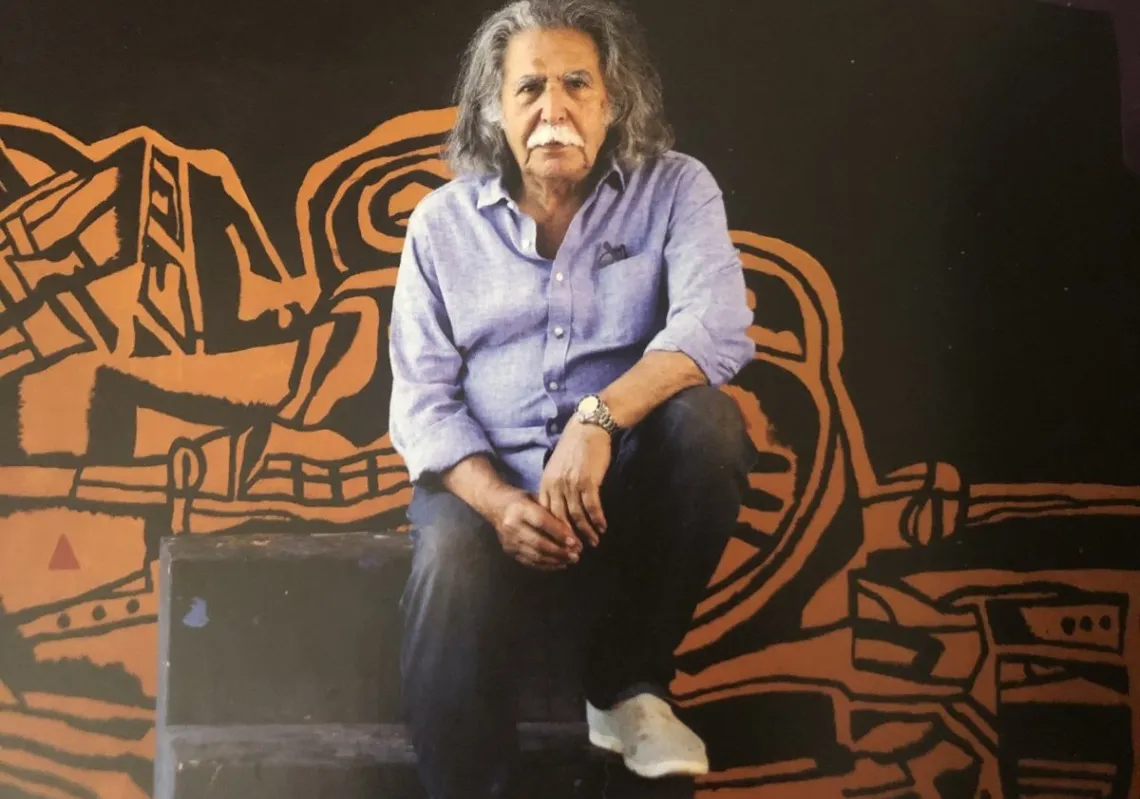

[caption id="attachment_55229266" align="aligncenter" width="620" caption=" Secretary General of the Arab League Nabil Al-Arabi (Khaled Desouki/AFP/Getty Images)"]

[/caption]

[/caption]

Nabil Al-Arabi was poised to crown a long career as an international lawyer and civil servant in Egypt’s foreign ministry after he accepted the position of Foreign Minister in the first post-Mubarak cabinet in 2011. Three months later, he became the Secretary-General of the League of Arab States. Now, thanks to the crisis in Syria, the forces that elevated him to this position could ensure that his career concludes with a failure.

Born in 1935 in Cairo, Al- Arabi began his training as a lawyer in the early 1950s, graduating from Cairo University in 1955 and entering the Ministry of Foreign Affairs the following year. He continued his education in America, graduating with a master’s degree in International Law from New York University in 1969, and completed a doctorate at the same institution in 1971. He would later go on to serve as the Egyptian Ambassador to India in between working as a legal advisor in the Ministry.

Al-Arabi was part of the negotiations of the Camp David Accords between Egypt and Israel, after which he was chosen to represent Egypt at the UN. He also became a judge in the International Court of Arbitration, stepping down in 2006, and at the International Court of Justice at The Hague.

Al-Arabi’s involvement with the Arab Spring began in earnest with his membership of the ‘Council of the Wise’, a group of 30 or so senior academics, technocrats, businessmen and lawyers who attempted to mediate between the occupiers of Tahrir Square and Mubarak’s government. Reportedly, he was the choice of many of the revolutionaries for foreign minister, replacing the widely-disliked Ahmed Aboul Gheit, when the cabinet was purged of figures judged to be too close to Mubarak in March of 2011.

Al-Arabi had previously called for reform of Egypt’s government in February, citing a need for increased transparency, more independence for the judiciary and the separation of powers between different branches of the government.

His criticisms of Israeli positions have given him a certain level of popularity, though he has been firm in his assertions that the peace treaty he helped negotiate in the 1970s should remain in force. Instead, he has criticized Israel for not living up to its obligations in its dealings with the Palestinians, and has rejected objections to Hamas’ involvement in government in Gaza.

A string of popular measures followed Al-Arabi’s appointment as foreign minister. First, he announced that the new Egyptian government would reverse Mubarak's Gaza policy and open the border crossing at Rafah, and declared his intention to visit the territory. Next, an agreement was brokered in Cairo in April between the two leading Palestinian factions, Fatah and Hamas, who had split bloodily after the ‘Battle of Gaza’ in 2007, following Hamas’ victory in the 2006 election. He also suggested re-opening diplomatic relations with Iran after a two-decade absence.

However, only three months into Al-Arabi’s tenure as foreign minister, the head of the Arab League, Amr Mousa, resigned his post in order to stand as a candidate in Egypt’s presidential election. Arabi’s selection surprised some observers, after last minute diplomatic wrangling left him the only candidate for the job, following the withdrawal of Qatar’s nominee.

He now faces a challenge that has the potential to overshadow all his previous accomplishments: trying to chart a new path for the League in the midst of the Syria crisis. Pushed by member states keen to shed the image of the organization as an ineffectual club for autocrats, he too reportedly desires to establish it as a relevant force in a new era while dealing with the Arab Spring's latest, and potentially greatest, crisis.

Even for a man who helped negotiate peace between Israel and Egypt, this could be an impossible mission. While both Israel and Egypt, pushed by the U.S., sought an agreement amicable to both sides, Al-Arabi now finds himself in a ‘no-win’ scenario: trapped between a paranoid Syrian regime that sees any calls to reform as a foreign conspiracy to undermine it, and an opposition who see attempts to mediate a peaceful resolution as a sell-out that leaves Assad in charge. Demands from some Arab League members, such as Qatar, for forceful measures to stop the violence have not made his task any easier. In such a situation, a diplomatic solution seems impossible, a galling blow to a man accustomed to negotiation, and who has spent his life in the worlds of diplomacy and arbitration.

As the Syrian tragedy unfolds, Al-Arabi finds himself buffeted by forces he cannot control, but only time will tell if he is able to maintain his grip. Despite his decades as a diplomat, it is his actions now and the near future that will determine his legacy and how he will be judged by history.