Few diplomatic moves carry so much significance as the appointment by Kuwait and Iraq of their new ambassadors to Baghdad and Kuwait City, respectively. With relations interrupted since the First Gulf War, the first major breakthrough came in July 2008, when the Kuwaiti government appointed Ali Al-Momen ambassador to Iraq. Then, in May this year, Mohammed Hussein Bahr Al-Uloom, the son of a prominent Shi’ite scholar whose family is revered for having fought long and hard to oppose both British occupation and the Ba’ath regime under Sadaam, was appointed as the new Iraqi ambassador to Kuwait.

These two diplomatic moves are tangible signs that both governments would like to fully capitalize on their common history and cultural ties. As Ambassador Bahr Al-Uloom explained to The Majalla, the new position was created, first of all, to show that the new Iraq recognizes its past aggression; second, to show that Iraq sees Kuwait as an independent, sovereign nation; and third, to help eradicate the deep distrust and hostility that resulted from Saddam Hussein’s invasion. In addition to the political motives of Al-Uloom’s appointment, both countries strongly believe that bilateral trade and investment will greatly benefit them and the wider Middle East region.

The relationship between the two countries has been a historical roller coaster. Kuwait gained its independence from Iraq in 1961, however, the Iraqi government claimed rights over the territory until 1963. From that point until the end of the Iran-Iraq War, bilateral political and military relations were strong. Since both countries shared a common opposition to the Iranian regime of Ayatollah Khomeini, Kuwait was one of Iraq’s most formidable financial and logistical supporters during the war. Nevertheless, at the conclusion of the conflict, relations began to erode due in large part to a dispute over oil drilling rights. This tension reached its high point in 1990 when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, which he nationalistically referred to as Iraq’s 19th province.

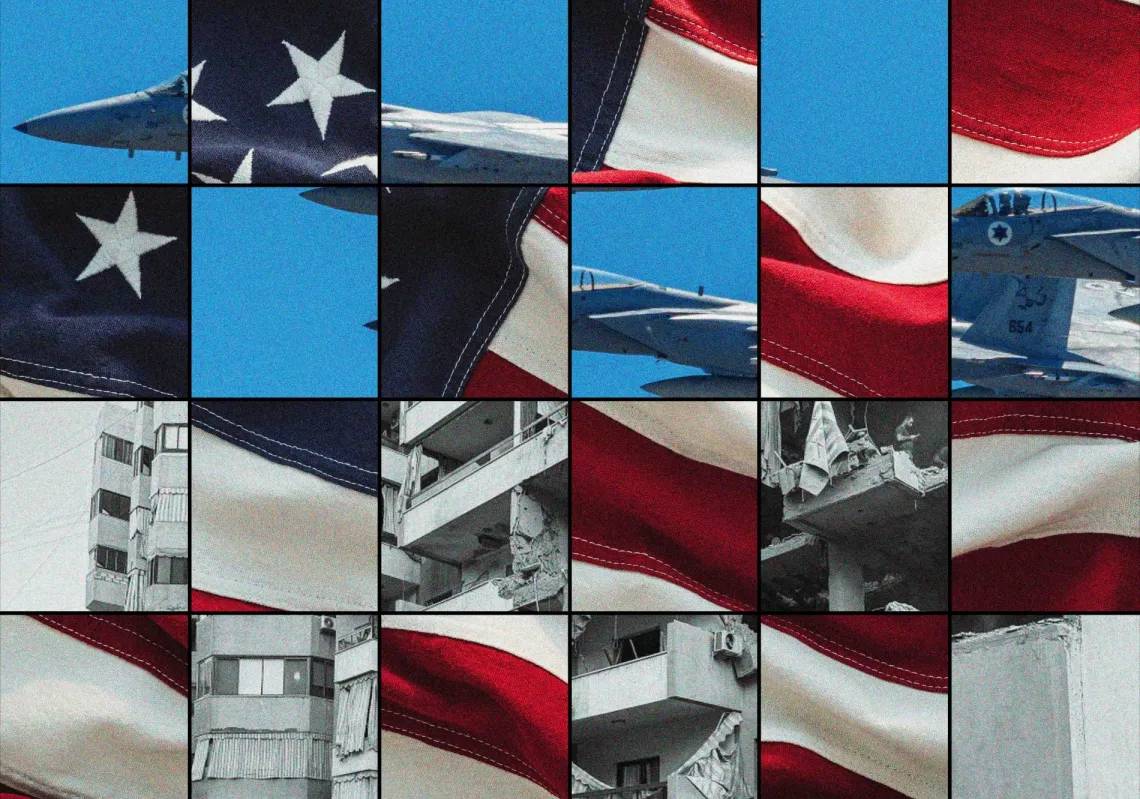

Kuwait had once been part of the Ottoman province of Basra, and therefore many Iraqis believe that they were victimized by unfair lines deliberately drawn by the British imperial powers to restrict Iraq’s access to the sea. The 1990 invasion of Kuwait, however, was only partly due to staunch nationalism; this was eventually superseded by the Iraqi government’s desire to revamp its economy with vast Kuwaiti oil reserves following the crippling financial effects of the Iran-Iraq war. The fracture in bilateral relations was further exacerbated in 2003 when Kuwait opened its territory to the United States as a means of invasion.

Since Saddam was ousted from power, the relationship between Iraq and Kuwait has improved dramatically. Kuwait has played an important role in the financial reconstruction of Iraq, and has also supported the Iraqi government in its efforts towards the establishment of a democratic political system.

Ambassador Bahr Al-Uloom hopes that this new bilateral era will lead to stronger diplomatic ties based on mutual respect and appreciation. Looking forward, however, several controversial issues remain unresolved. For example, Kuwait firmly believes it is entitled to recover an estimated $24 billion debt in reparation costs from Saddam’s Gulf War occupation. In response to this, Iraq currently transfers 5 percent of its quarterly oil and gas revenues towards this bill. Baghdad hopes that the UN Security Council will reduce these payments so it can use part of that money for internal reconstruction and development. Last year, a proposal was put forth by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon suggesting that Kuwait consider investments in Iraq as a way of resolving this dispute. Under the proposed plan, Kuwait would invest billions of dollars of unpaid compensation into Iraq in the form of joint ventures. This possible solution remains on the table, yet both sides need to study it further before reaching any sort of potential conclusion.

Another important point of disagreement is to define the exact land and sea borders between the two countries. This conflict dates back to British imperial rule. Earlier this year, Nouri Al-Maliki, Iraq’s prime minister, asked for the revision of the maritime border between the two countries. Some Kuwaitis judged this as a provocation and associated it with bitter memories of the Ba'ath regime’s aggressive policies; Saddam had used this argument to justify his 1990 invasion.

When the American government withdraws all troops from Iraq next year, this will present a tense period of uncertainty for its neighbor. Some Kuwaitis fear the possibility of sectarian conflict, which could potentially lead Al-Qaeda militants to cross over the border into their territory. Furthermore, although most Kuwaitis do not believe that another Iraqi invasion is on the horizon, due to past experience, Iraq is still commonly perceived as the number one security threat to the country. As one Kuwaiti told The Majalla: “Saddam was not the first one to believe that Kuwait should be part of Iraq, and I strongly doubt that he will be the last.”

In order to heal the deep, open wounds of the past, Iraqi Ambassador Bahr Al-Uloom and his Kuwaiti counterpart, Ali Al-Momen, must continue to foster the deep brotherhood that these two nations share. Geographical proximity and a partially common history make it a logical approach. Together, they can lead by example to promote peace and stability, curtail terrorist threats, and improve the prospects for the entire Middle East region.

In his recent interview with The Majalla, Ambassador Bahr Al-Uloom seemed eager to accept this new challenge. In the words of the ambassador, “It is my duty to promote mutual interests, especially in trade and economic investment, as a strong basis to develop deep ties between both countries. Iraq is a rich field for investment by the Kuwaiti capital that is invited to activate its work in different fields for the benefit of both states.” Not only in the economic sense, but at a more general political level, the ambassador reiterated that “the new Iraq is committed to the general principles of human rights, respecting national interests, strengthening its Arab relations, maintaining its Islamic identity, and being a positive and useful player in the international community. We want to send a clear message to the whole world that the new Iraq is a country of legal and constitutional institutions. Democracy in Iraq is real and true.” From these comments, it seems clear that a new era of bilateral relations has officially begun.