Recently, American diplomats and military men invoked the constant tensions in the Middle East, namely the Israeli-Palestinian quagmire, as a source of radicalization feeding, at least morally, the Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan, and consequently creating more problems for US and NATO troops on the ground. The logic behind this linkage is the following: It is impossible to look at the Afghan theater without highlighting the importance of stabilization across the Middle East. Apparently, from promoting defense reform and sound civil-military relations to preventing nuclear proliferation, NATO members have more interest in this region than in any other. Is this really the case?

There are two main narratives about NATO’s vision of the Middle East. One sees the region from Rumsfeld’s point of view, as a wider territory from Morocco to Pakistan, commonly known as the “greater Middle East,” viewed by the West as an area of concern on issues such as WMD proliferation, extremism, interstate conflict, failed states and civil war. The other is more focused on the hot spots, reducing all the problems to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and enabling NATO to redefine a wider strategic vision to the region, linking issues like poverty, development, human rights, security and nuclear proliferation.

The growing interest on the greater Middle East

The first direct link to the region was 9/11. Al-Qaeda’s safe haven in Afghanistan not only motivated the North Atlantic Council to invoke its article 5 for the first time in its history, but it also gave a crucial input to the first “out of area” operation in the history of the Atlantic Alliance.

NATO deployed a peacekeeping force of thousands of troops to northern Afghanistan and committed to expanding that mission to the south, adding more troops progressively. The Alliance’s involvement in this operation has been a work in progress since then, and Afghanistan remains the Alliance's key priority today. All 28 NATO allies are joined in the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) by as many as 16 non-NATO countries from all over the world, including Jordan.

In June 2004, the allies agreed to help train Iraqi military forces. They set up the NATO Training Mission and Joint Staff College at Ar-Rustamiyah near Baghdad, whose mission is to train and mentor mid-and senior-level Iraqi officers, and to implant values appropriate to democratically- controlled armed forces. In the aftermath of the greatest transatlantic crisis (2002-‘03), the Alliance agreed to commit its will, money and human resources to assist in the task of rebuilding a devastated country in the heart of the Middle East.

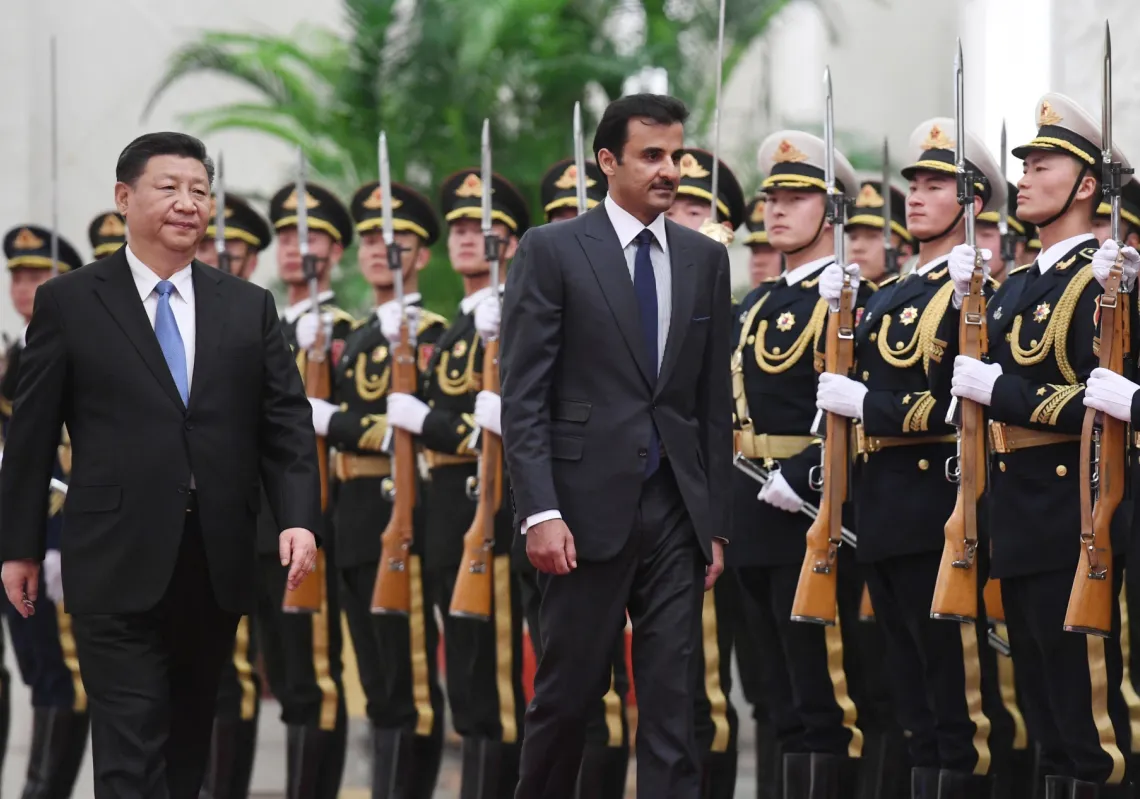

Also in 2004, NATO launched the Istanbul Cooperation Initiative to develop its political and military relations with members of the Gulf Cooperation Council—Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. More than 600 multilateral activities have been launched since then, ranging from counter-terrorism, through military education and training, to energy security and maritime cooperation.

In 2005, following an earthquake in Pakistan estimated to have killed more than 80,000 people and which left up to three million without food or shelter, Islamabad authorities requested international assistance. The Alliance deployed the NATO Response Force—a group of military forces that can be called at short notice and deployed anywhere around the world—in what represents a new type of operation for the alliance.

NATO also expanded its Mediterranean Dialogue, founded in 1994, to facilitate political dialogue with Middle Eastern countries, including Algeria, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia.

Finally, since 2008, NATO has been leading an international counter piracy operation in the Horn of Africa to protect merchant traffic in the Gulf of Aden under Operation “Allied Protector,” and as part of Operation “Ocean Shield” (until December 2012), to offer countries in the region the help to develop their own capacity to combat piracy.

One could ask if this approach will give the Alliance an extra responsibility to act on every security issue in the region. The answer is no. NATO will not become a security alliance for the Middle East as it was for Western Europe—with US and European bases scattered throughout the region. Nonetheless, despite all the differences among NATO members and the obstacles to a NATO role in the Middle East region, the fact remains that the United States and Europe will continue to have significant common security interests there. And NATO remains the best mechanism for coordinating their policies and operations.

The Albright Report

NATO will adopt a new strategic concept—the third after the Cold War—during the Lisbon summit to be held in November. The document, which was circulated for discussion to all member states, was developed by a group of experts led by the former US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright. According to the report, there are in the Middle East three main trends that affect the security of the Alliance: extremist violence, Arab-Israeli tensions, and the unwillingness of Iran to comply with the international community. This last point is suggested to be, in the foreseeable future, a threat to be included in the article 5 umbrella, which means that NATO may be forced to use force against Iran if the regime pursues a nuclear program for a military purpose. As Robert Gates recently put it, “Iran could launch hundreds of missiles at Europe”—maybe the reason to support a military attack on Iran among Europeans (Pew Research poll, 17 June 2010).

At the same time, the Albright report stresses improvements in NATO’s current partnerships in the region, and gives particular attention to a Palestinian-Israeli peace agreement under Alliance supervision, requested by the parties and authorized by the UN Security Council. In other words, the report suggests an intense and central role for NATO in the peace process in order to assist its implementation. The problem is that it doesn’t say how. Notwithstanding Alliance voluntarism on this issue, the questions remain the same: If NATO undertook a role in enforcing a peace between Israelis and Palestinians, would the parties on the ground consider NATO an honest broker, particularly after the Afghan campaign? Should this kind of role be the core business of the Alliance in the next decade? The report tries to be clear about that. First of all, it shows the will to be in the peace process; secondly, it defends an approach to NATO that defines its territorial framework—the Euro-Atlantic area—but emphasizes its strategic interests: the international arena where member states’ security is at stake. It remains to be seen if NATO member states will also be so clear about these issues during the Lisbon summit.

A weakness of the report lies in the topic of energy security. If there is a subject that deeply concerns NATO members it is the energy dependence of member states on the Middle East. Sixty-five percent of Europe’s oil and natural gas imports pass through the Mediterranean. In the view of NATO members, it is not only a question of dependence from an unstable region, but also a matter of security transportation in the sea, and the need to improve coordination between the navies. Also in this context, it is important to assume the centrality of Turkey—a NATO member—as a key energy transit state and major energy hub for European supplies.

Furthermore, safeguarding shipping in the Strait of Hormuz and in the Gulf of Aden is vital to the Euro-Atlantic zone: Up to 95 percent of the trade by EU states, and 20 percent of world trade passes through the Gulf of Aden, and approximately 15 tankers a day pass through the Straits of Hormuz, carrying about 17 million barrels of crude oil. This represents almost 40 percent of the world seaborne oil shipments—but most significantly from a Gulf States’ perspective, it represents 90 percent of the oil exported from the region.

While all these figures and issues will likely be on the table during the Lisbon summit, one thing seems certain: The problems of the greater Middle East are directly connected to Euro-Atlantic security interests.

Bernardo Pires de Lima – Researcher, Portuguese Institute of International Relations. He is currently writing a book about the reasons why NATO has survived the end of the Cold War.