I have always had a problem with the way popular culture has treated the reputation of the most famous of all the pharaohs. It simply lacks decorum, in my view, to refer to the boy king as Tut. Why the familiarity?

The Americans seem to have come up with the idea, no doubt to avoid the nightmare of spelling his name in full, but also because, well, they’re a republic – bowing and scraping to monarchs ought to be something they grew out of long ago. And yet, I can’t help feeling there’s something more than mere disdain for monarchy going on here. Could it be that the finery and makeup are considered effeminate, and that therefore Tut cannot be taken seriously? If this had been Alexander the Great, I doubt they would have referred to him as King Alex, although he did have that tranny phase in Persia. When Tut took the fashion industry by storm in the Twenties, it fell to the flappers to wear the mascara and beaded headpieces. You rarely saw men of the era sporting eyeliner unless they were Rudolph Valentino.

Aside from the lack of proper respect, I have never been sure how to pronounce Tut. On the face of it, one tends to opt for the ‘tut, tut’ of mild admonishment, of a kind the boy king would have been used to hearing every time he knocked over another vase of lotus flowers with his flail. One can rush to judgement here, but you try walking sideways and avoiding breakages. However, if we treat Tut as a literal abbreviation, it actually gives us King Toot, which is even more infantilising than Tut. You can’t help picturing Toot, as a tot, annoying the otherwise serene Nefertiti (not his real mum, by the way, just one of his dad’s wives) by fooling around with the ceremonial trumpets. Life in the palace must have been wearing for everyone concerned.

The pharaoh, it has to be said, would not have been particularly fazed by discussions over his name. Even in his short lifetime, there was some confusion about it, and his father had been just as bad, starting out as Amenhotep IV, meaning ‘Amun is satisfied’. He had to change this when, five years into his reign, he well and truly dissatisfied Amun by declaring that the Aten (the disk of the sun) was the only god worthy of reverence. Some polite people called this monolatristic. Others, more forthright, called it henotheistic, and there were those who didn’t mince their words and accused him of outright monotheism. In truth, he probably wasn’t that interested in the theological niceties; he just wanted to annoy the priests in Thebes, who had become too rich and powerful. Whatever his motives, Amenhotep duly changed his name to Akhenaten, which was no less of a mouthful, but had the advantage of meaning ‘effective for Aten’. In this way, he could force the priests to address him by what amounted to a short sentence and really rub their noses in it.

After changing his moniker in this tyrannical fashion, Akhenaten, the ‘pharaoh-formerly-known-as’, decided to name a son he’d just sired by ‘the younger lady’ (not Nefertiti), Tutankhaten. This meant ‘living image of Aten’. Now, given that Akhenaten saw himself as the image of Aten, if not Aten in the flesh, the name basically confirmed that the child had his father’s eyes, and it was another one in the eye for those pampered priests. Then the pharaoh shifted operations from Thebes and founded his own capital named, you guessed it, Akhetaten, ‘the horizon of Aten’, though people now prefer to call it Amarna. What had perhaps begun as a trivial spat, just a bit of a turf war with the priests, turned into a comprehensive triumph for Akhenaten that led to an overhaul of the entire state religion and imperilled the peaceful functioning of the Egyptian state. There’s a lesson in there for leave voters. Later, when his son failed to provide an heir to extend the eighteenth dynasty, the revenge of the nineteenth dynasty would be swift. Akhenaten was denounced as an enemy and ‘that criminal’. His statues were destroyed. For obvious reasons, he wasn’t even referred to by name unless absolutely necessary, and the scribes had their work cut out omitting to mention his reign in the court records. But I’m getting ahead of myself here. What, I hear you ask, about the son by the ‘younger lady’, this Tutankhaten we’ve never heard of?

Once the heretical pharaoh had met whoever his maker turned out to be, there was a brief reign by someone called Smenkhkare. This, some Egyptologists speculate, may actually have been Nefertiti. The ancients were not keen on allowing women to become pharaoh, and if you think what they did, eventually, to Akhenaten was bad, you should see how they treated the memory of Hatshepsut, who had even gone to the lengths of wearing a beard and, some say, dressing as a man, simply to pass as regal.

Which all goes to prove that, despite the irreverent newspaper headlines and the popular songs – even President Hoover’s German shepherd dog was called King Tut – the pharaoh’s name was a deadly serious matter. According to the Book of the Dead, the manual for the afterlife that has come down to us from the ancient Egyptians, it could mean the untimely interruption of a deceased pharaoh’s paradisal existence if their name wasn’t uttered any more, let alone erased from the records:

‘To have a name (Ren) was to have an identity. If your name was lost, you were no longer a distinct person and would cease to exist. As a result, tomb owners inscribed their names all over their tombs and texts begged visitors to say their name and so help them to flourish in the afterlife. The name of the pharaoh was magically protected by the cartouche. One Egyptian myth tells that Isis gained power over Ra himself by learning his secret name. It was possible to attack a person in the afterlife by destroying their name’ (Ancient Egypt Online).

The misfortune that befell Tutankhamun in his life, leading to his premature death, has been a matter for feverish speculation. Was it a fall from his chariot? A cranial injury to his mummy seemed to suggest this, until they concluded that it was the botched handiwork of his embalmers. He is thought to have been a weakling, possibly forced to carry a stick. Was he brought low by an infection in his foot? Or by an assassin?

What we can say for sure is that the succeeding dynasts did everything they could to obliterate his memory, owing to his filial guilt by association, and that in so doing they must have known they were attacking his immortal soul. Like Elvis, so long as he was spoken about, the king was in danger of being spotted, and not just in Memphis. He hadn’t yet entirely left the building. He was still on the loose.

So, quite ruthlessly, they removed Tutankhamun from the records. Like ancient Stalinists, they airbrushed him from history without a thought for his afterlife. Believe me, you don’t ever want to cross an Egyptian priest. Job done, they (and more importantly, the grave robbers) were free to forget him. They even repurposed the statues, by changing the names on the plinths.

When a new tomb was being constructed nearby, for Ramesses VI, the rubble ended up covering the entrance to Tutankhamun’s tomb. Already, the whole sorry business had been forgotten.

Aha, I thought, so that was how the bling managed to survive the usual attention of the thieves. A kind of collective amnesia. Obscurity was the key to Tutankhamun’s fame. He would have remained nameless without it.

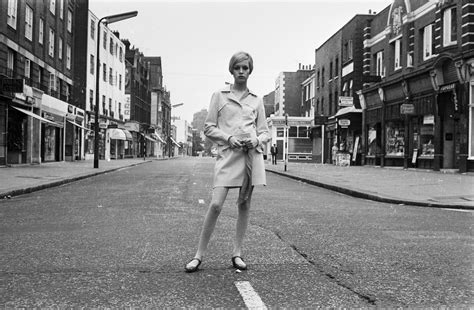

THE KING’S ROAD

On an autumn evening in London, some three thousand three hundred and thirty years (give or take a year) after the boy king was consigned to oblivion, some very posh-looking courtiers lined up for an audience. It had been a very cold, wet autumn so far, but on this particular night, as the queue formed outside the Saatchi Gallery, a little bit of Egyptian warmth seemed to be escaping from the interior, out through the tall columns of the portico, to greet the chattering throng. There was a low buzz of anticipation. A woman in a gold sequined dress glittered in the subdued light. Otherwise, everyone was rather sombre, the men in lounge suits and the women in long black dresses. The glow of gold sequins against this background of black was calculated to make Tutankhamun feel right at home. It was the King’s Road after all. The acme of fashion. It’s what he would have wanted. Besides, there was something funereal about the black suits, serving to frame the promise of eternity scintillating in the gold dress.

Like everyone else, I’d been drawn there by the irresistible fame of the man they tried to snuff out, whose refulgent allure had already seen them queueing round the block in Paris only a week before, and whose effortlessly glitzy Ba (or soul) has fetched up here, in dreary London, in the shape of the gorgeous artefacts from his private collection. Some of them have never left Egypt before, and – after touring the world one last time – none of them will ever leave it again.

So, a sharp intake of breath, darling. The camera loves you. Prepare to become drunk on beauty, and take notes, because no one, but no one, does aesthetic intoxication quite like the ancient Egyptians.

Once I got inside, it was hard to believe that the beauty and splendour of the boy king’s stuff was supposed to remain hidden in a dark tomb, for ever. They must have had complete faith in the Book of the Dead and the entire project of immortalising their kings; anything less, and it would all have felt like an appalling waste of effort.

There is a story that Donatello took obsessive care over the backside of a statue of David, I think it was, that was destined to adorn the exterior wall of a building. “Why bother,” he was asked, “since no one will be able to see the back of the statue?” A lesser man might have been rattled by this question, particularly if, like Donatello, they were accustomed to fending off accusations that the backside was the only part of the anatomy they cared about. Unruffled, the sculptor smiled indulgently at his interrogator. “God can see it,” he replied.

Everything before me now was for the eyes of the gods only. None of the treasures here were intended to be touched by the light of day again, and the curators had almost stayed true to this intention. The gallery’s rooms were shrouded in darkness. Only through gloom, as our eyes adjusted, were we able to see the objects, thanks to a bare minimum of illumination. For the makers of these objects, there must have been a kind of sanctity in darkness itself. The man who uncovered it all broke into that sanctity. His immediate transgression, even before he removed the contents of the pharaoh’s tomb, was to let the first ray of sunlight in on the mystery.

The effect of the semi-darkness was to make me feel slightly transgressive too. Judging by the hushed voices, I was not alone. Incredible to think that we were only able to see this because the first ‘robber’ to reach it had been a British archaeologist working on a hunch. Not even a very good archaeologist, if one believes the opinion of Flinders Petrie, an excellent archaeologist, who employed him on an excavation of Akhenaten’s old city. Petrie liked the boy: Carter was roughly the same age as Tutankhamun had been when he died. It was the first time the callow young Englishman had heard about the pharaoh. Petrie considered him “a good-natured lad, whose interest is entirely in painting and natural history,” adding: “It is of no use to me to work him up as an excavator.”

Oh, the irony of it. If the priests were right about names having to be repeated to ensure immortality, then poor old Flinders will just have to make do with the fond recollections of fellow Egyptologists. Howard Carter was destined for greater things. When his sponsor, Lord Carnarvon, asked if he could see anything beyond the sealed door, Carter replied “Yes, wonderful things!”

They are still just as wonderful today and, like Carter, one can barely see them at first, let alone photograph them: many of the finest pieces are in gilded wood that seems to glow with its own light, yet in photographs the rich lustre of the gold is replaced by an over-lit glare of yellow, and all the detail is lost. Unable to capture the sight with a camera, one is forced to savour the moment, or else store it in the memory.

Tutankhamun’s features and svelte body, striding or standing sentinel, are everywhere, glowing gold. At one point we see him hunting hippos, in another guise he guards the entrance to his own tomb, tall and black as the fertile silt of the Nile. The smaller figurines have the ambiguous gender we associate with the pharaohs. One representation in particular looks exactly like a young woman, with the hips and breasts of an hour glass figure. In other instances, we sense the machismo of an ancient monarch, enacted (like monarchs throughout the centuries) in the hunt. This is the warrior who turns on the local fauna and destroys them for his pleasure. But it was not just hippos that needed to fear him. Nubians are trampled underfoot. Captives are depicted on objects that have nothing to do with warfare or hunting. It is as if the boy king will triumph over death – this is not just a tomb, after all, but a magical time machine – through sheer arrogant contempt for his enemies.

And yet this machismo has to coexist with the pampered effeteness of a boy reared in unimaginable luxury. Toy skiffs idle on invisible rivers, small enough for a boy to sail on the pond in his local park. When needed, they will transform into full-sized boats for the pharaoh’s spirit to make its way to paradise. Elsewhere, he is depicted as a winged sphinx. In the introductory film, the closing image is of Tutankhamun taking flight. But not yet. Snug, like a swaddled babe, deep inside his multi-layered Russian doll of sarcophagi, which are carved in his likeness, the boy king who died around 1,326BC is still dreaming of becoming a butterfly, and in strange, eerie sympathy, the sphinx-butterfly is dreaming of becoming him.

There are many gorgeous treasures, such as the inlaid cabinet on slender legs or the alabaster vessels faintly translucent in the gloom, but one object lured me back, again and again, and it’s a fan. Not the entire fan, but the wooden pole and golden lotus of the part where the ostrich feathers would have been mounted.

The carving is too exquisite for a smartphone camera to pick up. You really have to linger over the carvings and look at them. Here we see remarkable animation, as if the ancient Egyptians had never specialised in stylised, rather stiff figures walking among hieroglyphs. Tutankhamun is dashing along in a chariot, firing arrows as he does so, and in front of his vehicle a hound tears along at full pelt, legs stretched before and behind, almost visibly salivating. To the right, the quarry of the king, are two confused looking ostriches who will die for the sake of the fan industry. One of them has a bolt right though its back and turns in agony towards its tormentor, the other seems to be mortally wounded and is already on the ground. They are not very accurately pictured, but you can just make out their stumpy, useless wings and the tail feathers the pharaoh is after. His chariot is pulled, rather alarmingly, by two rearing horses. The air is thick with hieroglyphs, but if we look closely at the hieroglyph that seems to be striding along behind the chariot, we see that it is humanoid and carrying its own fan, crested with ostrich plumes.

The scene is a perfect example of the strangely effete machismo that I was describing: even in the heat and haste of the chase, the pharaoh must be cooled by a fan borne by one of his minions, a fan that no doubt depicts another chase, and in that chase another fan, so that we have a fan with a kind of infinite self-reference, as eternal as the chase itself.

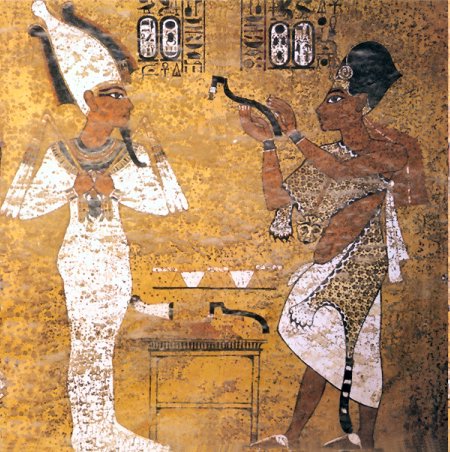

According to some lurid theories for the king’s death at so early an age, it was a man with a fan who did for him. Tutankhamun’s successor, by the name of Ay, was the ‘Fan-bearer on the Right Side of the King’. This was a very important position, signifying that the bearer of the title had the ear of the ruler. Ay was old by ancient standards, in his sixties by the time Tutankhamun died. He had already been influential over one, perhaps two of the king’s predecessors, a survivor, and the novelists have succumbed to an irresistible temptation to portray him as the villain of the piece. The younger man’s tomb contains a mural depicting Ay, in a leopard’s skin, performing the mysterious Opening of the Mouth ceremony on a statue of Tutankhamun. Or was he just making sure the young king was dead?

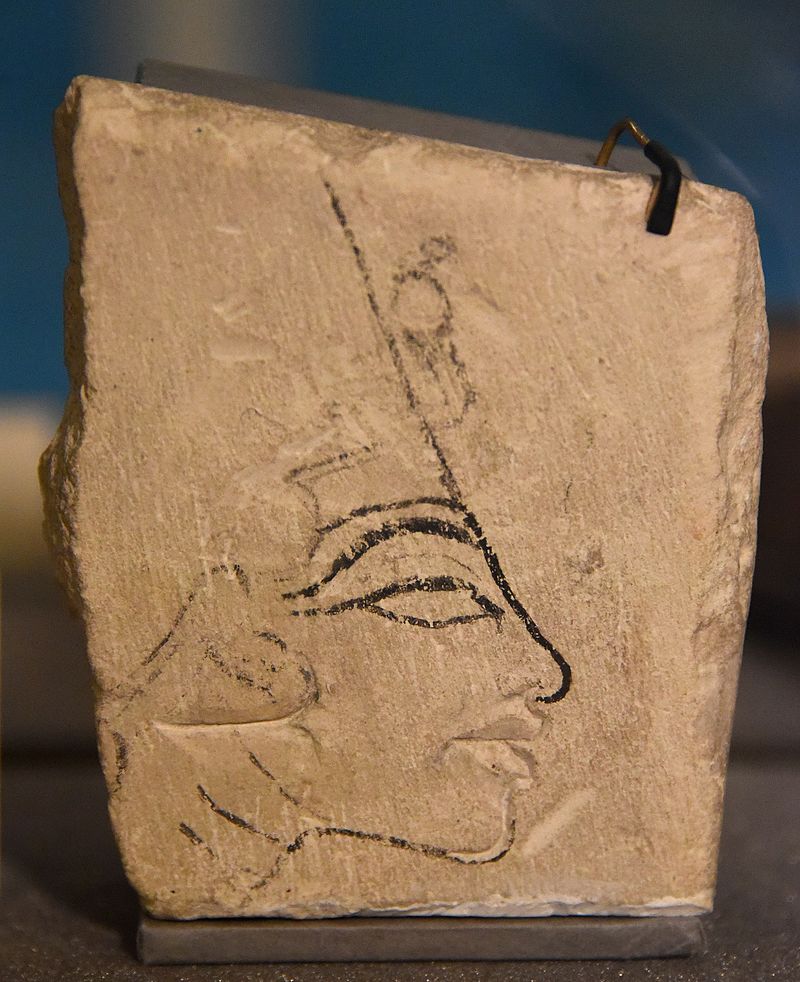

For such an old man, he looks suspiciously lissom in that leopard skin. Prettier, arguably, than Nefertiti looked in some of her representations. Ay remains, however, a shadowy presence. It is always Nefertiti, with all her charisma, one comes back to, but having marvelled at her bust in Berlin, I was a little disappointed to discover that ‘the beautiful woman has come’ (as her name translates) could actually look so frightful, you wouldn’t touch her with a Nilotic barge pole.

Ugh, give me Amanda Barrie in a bath filled with asses’ milk any day – yes, I know, that was Cleopatra, not Nefertiti. This rather stern and not so beautiful image may well belong to a later date than the famous bust. Back in the days of her marriage to Akhenaten, when the family moved to Akhetaten and adopted a different religion, she and her spouse were the only true receivers of the Aten’s life-giving rays, which they then dispensed to the people. They must have felt like they had the costa del sol all to themselves, beaches (well, sand) stretching as far as the eye could see, and for a woman of the elite class, lying around on a sun lounger was a way of displaying piety. Even the temples in Akhetaten were exposed to the sky. After laying off the priests and sculptors in their thousands, now that there was no demand for offerings or idolatrous statues, the royal couple could spend the entire day in peace, catching rays from the disc and, even better, feeling righteous about it.

But it couldn’t last. With the death of her husband, the sun worshipper in chief, Nefertiti suddenly had her work cut out. Having done nothing more strenuous than smite the occasional fly with a swatter, she now had to smite the country’s multitudinous enemies. Before long she would become a full-time male impersonator, and thus she would complete the narrative arc from celebrated glamour-puss to hackneyed circus act, a cross between the lion tamer and the bearded lady. By the time she’d smitten her way into an early grave, it was Tutankhamun’s time to take over smiting duties, and when he was worn out by the sheer strain of it all, in stepped the villainous Ay.

It’s a good story, but probably not one I could ever verify, since Ay’s short reign was followed by that of Horemheb, and his main contribution to world history was to expunge the part of it containing his immediate predecessors. In the absence of facts, one must resort to scarcely plausible fiction. They say the Aten had male and female characteristics and so, apparently, did its worshippers. Personally, I reckon the Nile contained high levels of oestrogen (you heard it here first), which was dumped as effluent by the priests to undermine the monarchy – how else to explain that oddly epicene look the royals had?

One poignant fact remains undeniable: that a boy king who had been reared in the ways of sun worship, ended up disregarded in a pitch-black cubbyhole, surrounded by objects of bewitching beauty that no one was ever supposed to see.

It makes you think, but only for a while. We mortals have our needs. Having supped long on so much forbidden beauty, I began to hunger for actual sustenance. Rumours were abroad that canapés, the food of the twentieth-century gods, were being served on an upper floor, so I squeezed into a tiny lift to be carried skywards. At least, that was my intention. Instead, along with nine or ten other over-dressed guests, including Philip Hammond who had recently quit the Treasury, I descended to the basement. There was a momentary thrill of panic, a sense that things were getting out of control. As we approached the bottom floor, it occurred to me how fitting it would be to get trapped together, held by an invisible force that prevented us from ever leaving the bowels of the building. It would be as if Carter had turned to see the entrance of the tomb slowly re-seal itself behind him, and as the crack of African sunlight dwindled, the last rays of the Aten would be accompanied by an ominous voice reciting the words of the Great Hymn:

You are in my heart,

There is no other who knows you,

Only your son, Neferkheprure, Sole-one-of-Re [Akhenaten],

Whom you have taught your ways and your might.

[Those on] earth come from your hand as you made them.

When you have dawned, they live.

When you set, they die.

Then, eternal darkness.

Disappointingly, the confusion over the direction of the lift got resolved as soon as the Chancellor of the Exchequer found the buttons and worked out how to operate them. The mummy’s curse failed to materialise and, in a few minutes, I would discover that canapés are indeed the food of the gods, and not as pointless as I’d always imagined.

Tutankhamun: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh is at the Saatchi Gallery in London till 3 May 2020.