The vote, which was brought forward after the death of President Beji Caid Essebsi on 25 July, and has widely been viewed as a test of one of the world’s youngest democracies, handed a blow to the political establishment, including for Prime Minister Youssef Chahed, who won just 7 percent, and former interim President Moncef Marzouki, who had a mere 3 percent.

A divided establishment created the opportunity for outsiders to claim both top spots in the run-off. For most of the eight years since the revolution, Tunisian politics has been organized around two large blocs: one centered on the Islamist Ennahda party, and the other centered on the late president Essebsi’s Nidaa Tounes party. Originally opposed to each other, these blocs reached a consensus agreement in 2014 election and have participated in a coalition government for much of the past five years. But the 2019 election marked the end of the Islamist-secular divide. No fewer than six candidates campaigned for what can be referred to as “secular establishment” – the progressive, modernist came originally affiliated with Nidaa Tounes, and one of the biggest surprises was perhaps the poor performance of Ennahda who despite moderating its image and selecting lawyer Abdelfattah Mourou as its candidate, only won 11% of the vote.

This sharp rebuke of the establishment was a long time coming.

WORSENING ECONOMIC WOES

In what was hailed as a sign of its successful democratic transition, Tunisia held its first-ever televised debate of presidential candidates earlier this month. The country has won praise for its democratic transition resulting from the 2011 Arab uprisings that began in Tunisia, before spreading across the Middle East and North Africa. But it has not all been smooth sailing. In the eight years since the 2011 revolution, successive governments have failed to deliver on the primary demand of the people: economic opportunity.

Promises of democracy have been undermined by the lack of economic progress which is worse than the pre-2011 conditions that led to the revolution. Nationwide, unemployment which was roughly 12-14 percent pre-revolution, has jumped to 18 percent in 2011 and remains at 15 percent today, with youth unemployment reaching around 45 percent. The cost of living has also been rising rapidly, increasing by more than 30 percent since 2016. The dinar has lost half its value since the revolution. GDP growth is sluggish, though it did rise to 2.6 percent last year. An IMF-backed reform program that aims to cut the budget deficit has brought higher taxes and unpopular efforts to freeze public-sector wages. Along with widespread poverty, high inflation, and a wave of terrorist attacks that damaged the economically vital tourism industry, these difficult conditions have contributed to frustration with not just the ruling parties but the entire political system.

In recent years, the political landscape has shifted significantly as electoral coalitions have been made and unmade, and as established political parties have fractured into smaller parties or collapsed amid leadership disagreements. The first round of the election was marked by high rates of apathy among young voters, pushing ISIE head to put out an emergency call to them Sunday an hour before polls closed. The most recent published Arab Barometer surveys (2016) reveals diminishing trust in the political process and institutions. For example, 65% of Tunisians have low or no trust at all in the government, 57% have little or no trust in the legal system. And 72% have little or no trust in parliament.

Leading up to the elections, analysts and politicians said a lack of economic progress could pose a threat to Tunisia’s democratic project. The International Crisis Group, a think-tank in Belgium, warned of a “general crisis of confidence in the political elite” in Tunisia. The group urged the European Union to support measures that would prevent further polarisation, including macro-financial assistance, reforms to public administration and the creation of a politically diverse Constitutional Court.

ANTI-ESTABLISHMENT VOTES

It is unsurprising; therefore, that both of the top two candidates – although very different – are seen as anti-system votes as neither come from political parties currently represented in the legislature and have capitalized on the general political and economic hopelessness many Tunisians feel.

Nabil Karoui’s appeal is easy to understand as it has been pitched against a sense of growing disillusionment. Despite his wealth, the media mogul - who founded Nessma TV alongside Silvio Berlusconi which he has used to promote his political ambitions - has positioned himself as the champion of the poor and “forgotten” Tunisians. He cultivated this image by hosting a charity show since 2017 in which he aired images of himself delivering aid from a family charity to the poor.

Karoui has promised a “revolution at the ballot box” in favor of the “other Tunisia” – the millions neglected by the establishment and has promised a strong state that can restore economic growth and deliver goods and services to the people. Among his popular promises, the Qalb Tounes head has pledged to invest in education, clean water, and other basic services for the poor.

The criminal charges against him, which he denies and calls them politically motivated, only added to his reputation as an outsider loathed by the establishment. In tandem to his arrest, Tunisia’s electoral and media authorities banned the popular Nessma TV, as well as two other stations, from reporting on the presidential campaign, accusing them of broadcasting without licenses. For many Tunisians, Karoui’s arrest 10 days before the campaign, was reminiscent of the country’s autocratic past and points to the rapidly eroding institutions and therefore worked in his favor. It mobilized voters in a key section of Tunisian society that feels side-lined by the economy and detached from the main political trends. His critics, however, describe him as an ambitious, unscrupulous, populist. The wealthy secular political elite, which he once backed, now view him as a threat.

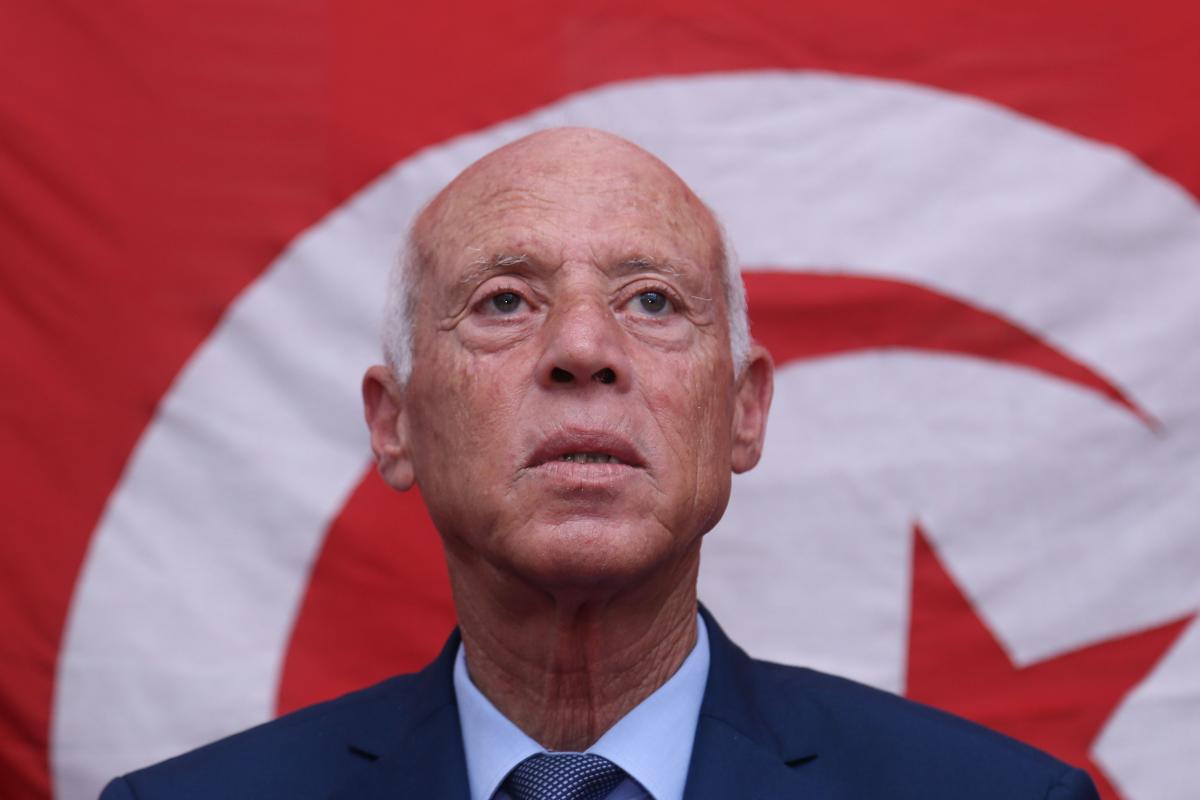

Karoui’s wealth and massive electoral organisation stand in sharp contrast to his rival, Kais Saied, who gathered 10,000 Tunisian Dinar ($3,400) from friends and family to pay a deposit required of candidates by Tunisia’s electoral body and launched a shoestring campaign in which he rejected state election funds and large rallies, favoring door-to-door campaigning. The frequent legal commentator on TV, who earned the nickname “Robocop” for his monotone, mechanical style of debating in classical Arabic, has presented himself as a humble public servant – taking public transport, pledging to continue living at his humble home instead of the luxurious presidential palace –evoking an image of an honest man, resistant to corruption by power.

Saied is devoid of any prior political experience, having never held political office or even voted before Sunday. He appeals to youth, especially disillusioned revolutionaries, by promising a new system: one in which power will be more decentralized, “so that the will of the people reaches the central power and puts an end to corruption.” The social conservative, who wants to restore the death penalty and rejects equal inheritance for men and women, is promising sweeping constitutional reforms, including empowering Tunisians to recall their parliamentarians. Claiming that the “era of parliamentary democracy is over,” he has also proposed eliminating parliamentary elections altogether in favor of a “bottom-up” approach where parliamentarians will be chosen from elected local councils, wielding significant regional autonomy.

THE ROAD AHEAD

The road ahead for the run-off election between Said and Karoui is uncertain. A critical predictor of how each will perform will be who the losing parties endorse, which will be crucial for the candidates to get to 50%. Saied, socially conservative and relatively pro-revolution, may appeal to Ennahda voters, while Karoui, anti-Islamist, and ex-Nidaa Tounes, may appeal to the secular establishment.

October's legislative vote comes next, offering another test of whether Tunisians will continue to sanction the political establishment. Under the current constitution, these parliamentary elections are ultimately more important than the presidential ones, as the prime minister – the stronger of the two executives – derives his or her power from the parliament. Campaigning has already begun, but Saied will be absent as, without a political party, he will have no direct representation in the parliament. Karoui’s newly-formed party, Qalb Tounes, by contrast, had been leading the pre-election polls for parliament.

With two elections in the coming weeks, Tunisia’s political landscape could be radically reshaped for years to come.