Egypt has asked Interpol to help track down a 3,000 sculpture of the famed boy Pharaoh Tutankhamun after it was sold in Christie’s in London for almost £5 million to an anonymous buyer in one of the most controversial auctions in years, despite Egypt warning it was probably stolen in the 1970s.

Tutankhamen is the most famous of all Egypt’s pharaohs, even though he only ruled for nine years and died before his 20th birthday. Zahi Hawass, Egypt’s former Minister of Antiquities said the piece appeared to be looted from the Karnak complex just north of Luxor.

In an extremely rare intervention, Egypt’s National Committee for Antiquities Repatriation (NCAR) asked Christies, the UK Foreign Office, the UK cultural body and UNESCO to intervene and halt the sale. Right up until the day of the auction, the Egyptian ambassador to Britain, Tarek Adel, called for the sale to be delayed so that its provenance could be further investigated. When Christie’s went ahead with the auction, the bitter row escalated between the two countries. The NCRA held an urgent meeting on Monday night and said in a statement that it hired a British law firm to file a lawsuit against the auction house, saying Christie’s did not provide documents proving ownership of the 11 inches high and carved from brown quartzite Tutankhamen who is portrayed wearing the domed crown of his namesake, the god Amun.

The repatriation committee expressed its deep indignation at "the unprofessional way in which the Egyptian artifacts were sold without the provision of the ownership documents, and proof that that the artifacts left Egypt in a legitimate manner, till this date.” NCAR also expressed "deep bewilderment that the British authorities failed to provide the support expected from it in this regard.”

Speaking to the BBC, Egyptian antiquities minister Khaled al-Enany vowed to repatriate the artifact. “They left us with no other option but to go to court to restore our smuggled antiquities,” he said. “We will leave no stone unturned until we repatriate the Tutankhamun bust and the other 32 pieces sold by Christie's. This is human heritage that should be on public display in its country of origin.”

The BBC reported that a number of Egyptian businessmen and civil society groups have pledged to fund the lawsuit. The UK has also been asked to prevent the export of Egyptian artifacts before Egyptian authorities have checked ownership documents, Egyptian sources say.

However, Christie’s has strongly denied any wrongdoing, insisting that all necessary checks were made over the bust's provenance and that its sale was legal and valid. “While ancient objects by their nature cannot be traced over millennia, Christie’s has clearly carried out extensive due diligence verifying the provenance and legal title of this object,” the auction house said in a statement. It stated that Germany's Prince Wilhelm von Thurn und Taxis reputedly had it in his collection by the 1960s, and that it was acquired by an Austrian dealer in 1973-4. That, however, was called into question when Viktor von Thurn und Taxis, the son of the minor German royal, told website Live Science that he did not recall his father ever owning the bust. He was “not a very art-interested person”, Wilhelm’s niece, Daria, added.

THE WIDER ROW

Over the past five years, Egypt has recovered 1,500 illegally trafficked objects from abroad. The country’s campaign to recover lost art gained momentum after numerous works went missing during the looting that accompanied former president Hosni Mubarak's fall from power in 2011. The Arab uprisings and the political unrest it sparked opened a gap for smugglers to operate mostly unnoticed in the country. Since 2011, the US-based Antiquities Coalition estimates $3 billion worth of Egyptian antiquities have been smuggled out of the country. However, those caught breaking the 1983 Protection of Antiquities Law face severe consequences including mandatory prison time and huge fines.

Cairo has managed to regain hundreds of looted and stolen artifacts by working with both auction houses and international cultural groups. For example, in January of this year, an Egyptian stole tablet of King Amenhotep that had been smuggled out of Luxor, Egypt, was rescued from a London auction house after the Egyptian antiquities ministry scored auction websites across the world. The sale was halted and the artifact was returned to the Egyptian embassy in London in September.

Auction houses and museums are increasingly facing scrutiny over the provenance of the antiquities on display and for sale. In April this year, the Ethiopian government rejected an offer from the Victoria and Albert Museum to loan back artifacts allegedly plundered by British forces in 1868. Ethiopian government minister Hirut Woldemariam told news agencies at the time that “we have asked (for) the restitution of our heritage, our Maqdala heritage, looted from Maqdala 150 years ago.” While Ephrem Amare, Ethiopian National Museum director, said: “It is clearly known where these treasures came from and whom they belong to. Our main demand has never been to borrow them. Ethiopia’s demand has always been the restoration of those illegally looted treasures. Not to borrow them.”

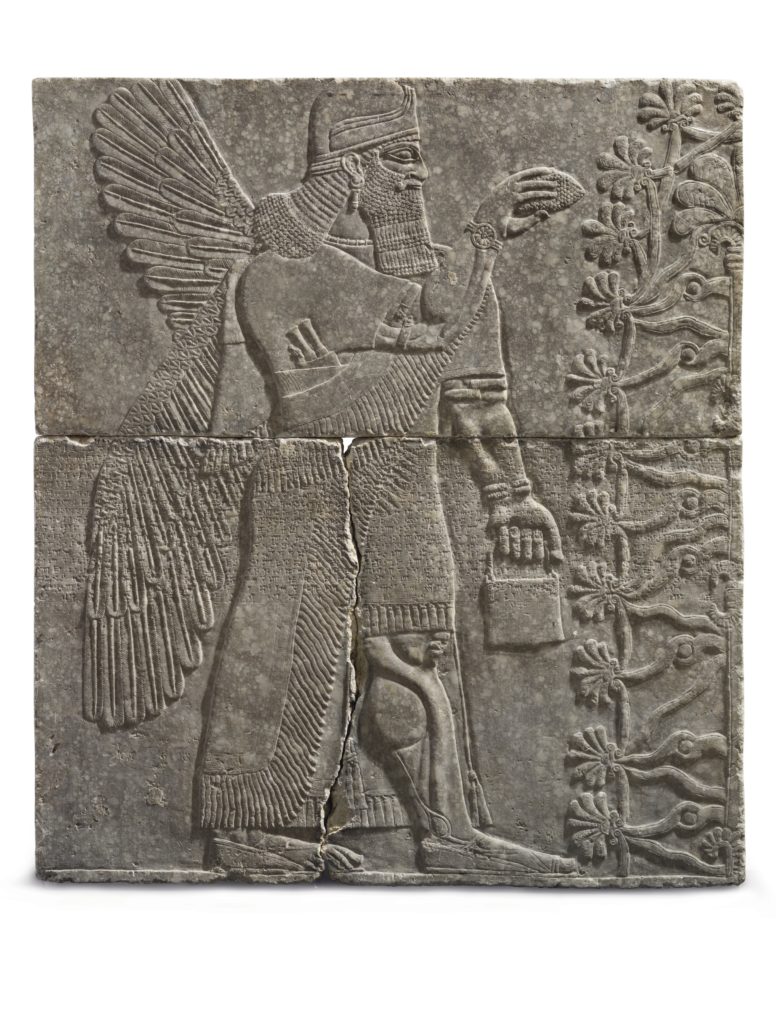

Last October, Iraq objected to the sale of a 3,000-year-old Assyrian stone relief when it was sold at Christie’s in New York for $31m. The Foreign Ministry had demanded the return of the rare sculpture just hours before the auction house sale, claiming it belonged to the country and is a looted piece of its heritage.

Christie’s was embroiled in another contentious sale last month when it sold Indian and Mughal-era jewels, daggers and royal portraits for $109 million, the highest total for any auction of Indian art and Mughal objects, and the second highest for a private jewelry collection. Aditi Natasha Kini wrote in the New York Times that it is not enough to have the legal ownership and that the “auctioning of stolen heritage to the highest bidder is widely unethical. These objects must be given back.”

The Financial Times wrote that sales of antiquities are “increasingly sparking disputes over provenance by authorities in countries of origin such as Egypt, Greece and Turkey. They argue that, despite restrictions imposed by international conventions and increased scrutiny by museums and auction houses, illegally acquired pieces still find their way to the art market.” That doesn’t surprise Peter Watson, who said in The Times that auction houses are too careless about looted antiquities and play a cynical game: “Sail as close to the wind as you dare, and when you are found out, do whatever you can to avoid admitting the unattractive truth”.