The fall of the Assad regime has marked a turning point for civic space in Syria, but the shape of that opening remains uncertain. Accounts from inside the country diverge sharply, offering contrasting pictures of how far public space has truly expanded.

Some describe an unprecedented shift. The pervasive fear that once governed public life has receded, allowing civic activity to re-emerge on a scale unseen in half a century. Associations are registering with relative ease. Public gatherings have returned. Officials are criticised openly in ways that would once have been unthinkable.

Others see far less change. They point to the persistence of restrictive laws, discretionary oversight and familiar red lines inherited from the Assad era. Political parties remain suspended, outdated legislation is still in force, and local authorities continue to wield broad powers to permit or block civic activity.

These accounts are not competing interpretations of a single reality. They reflect parallel realities unfolding simultaneously, experienced by different Syrians in different places and across different forms of civic life. In today’s Syria, civic space has expanded in practice while remaining constrained in structure. Openness and restriction coexist, shaped by geography, political sensitivity and the discretion of individual officials.

Understanding this moment, therefore, requires moving beyond binary judgments. The question is not whether civic space is open or closed, but how an expanded yet fragile environment is being selectively allowed, managed and constrained—and what that reveals about the limits of Syria’s political transition.

A hybrid civic space

Under Bashar al-Assad, civic space existed largely as a legal fiction. Freedoms of association, expression and assembly were formally recognised but systematically hollowed out. Security agencies and bureaucratic gatekeepers determined who could organise, speak or gather, and on what terms. Independent activism was obstructed, intimidated or eliminated.

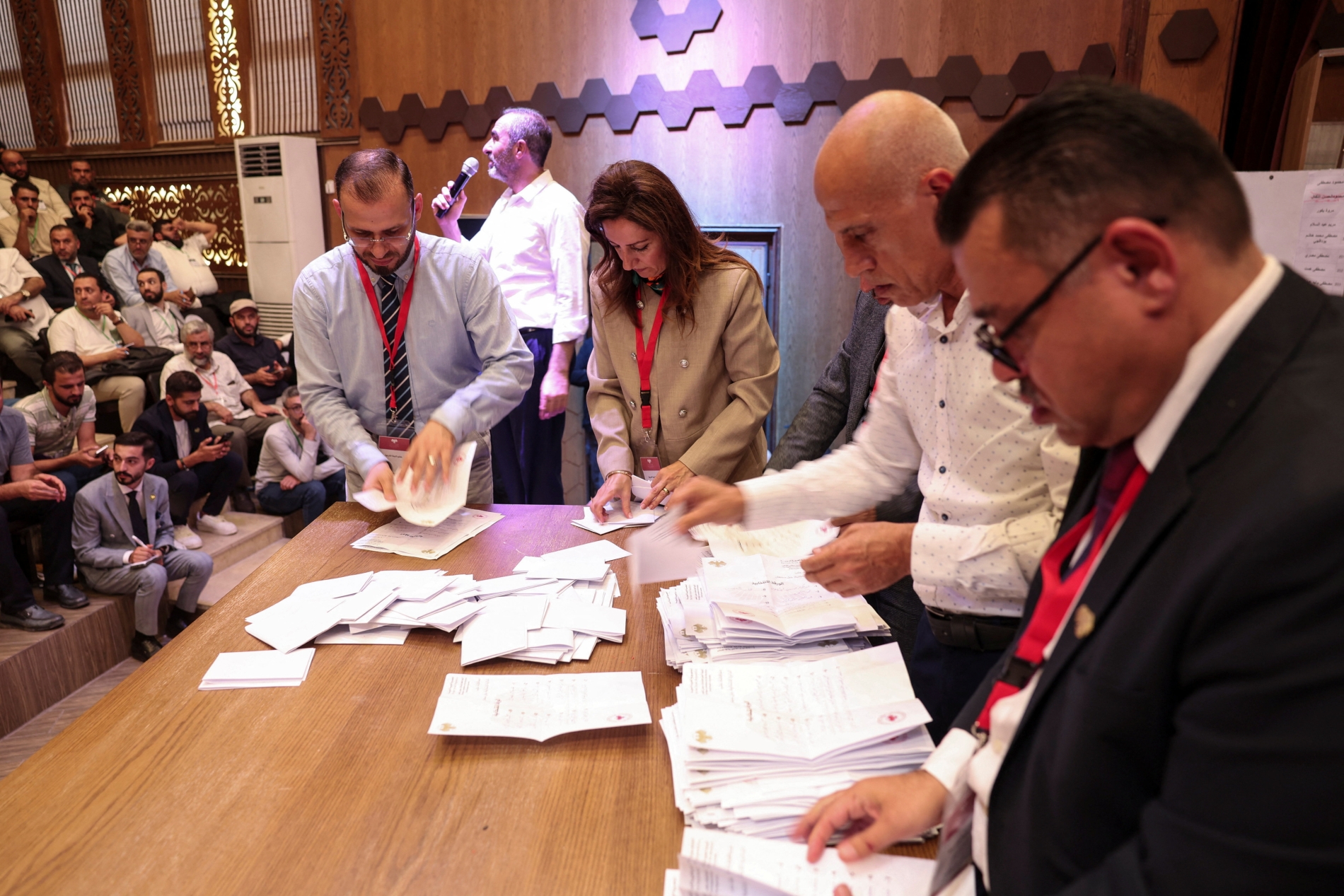

That system fractured with the regime’s collapse. In cities once firmly under state control, particularly Damascus, Syrians have begun reclaiming public space. Demonstrations have reappeared, community forums have emerged, and new associations are forming. Civil society groups report fewer obstacles to registration. Transitional authorities now speak of participation and transparency—concepts long absent from official discourse. For the first time in decades, public space is functioning as a site of civic debate rather than an instrument of control.

Yet the opening is uneven and fragile. The March 2025 constitutional declaration affirms basic civic freedoms but qualifies them with broad caveats tied to public order, morality and national security—the same elastic concepts long used to restrict civic life. Rights remain contingent on political tolerance rather than legal protection.

Much of the old legal and administrative architecture remains intact. Civil society operates within a patchwork of outdated laws, discretionary practices and fragmented authority. The same activity may proceed unhindered in one locality and be quietly blocked in another. Access to information lags behind other freedoms, while public participation ranges from meaningful engagement in some areas to symbolic consultation in others.

What has emerged is a hybrid civic space: visibly wider, but structurally unstable. New forms of engagement are possible, yet their limits remain negotiable—and reversible.

The human factor

Personalities have played an outsized role in shaping civic space during the transition. With rules unclear and mandates overlapping, outcomes often depend less on formal policy than on the disposition of individual officials. Some rigidly enforce inherited regulations, requiring approval even for meetings held inside the offices of civil society organisations and discouraging venues from hosting events without prior clearance. Others take a more permissive approach, allowing activities to proceed informally, particularly in cultural or semi-public settings.

The result has been uneven access. Some civic actors encounter constant red tape, with requests stalled, permissions delayed and events cancelled, while others move forward by navigating informal channels or relying on personal judgement about what not to ask for. Disparities between national and local authorities further compound this fragmentation, with local officials at times blocking activities approved at higher levels.

Political background, reputation and personal relationships have also shaped how organisers are treated. Well-connected or politically aligned groups often face fewer obstacles, while lesser-known or politically sensitive actors are subject to greater scrutiny. In this discretionary system, civic space is defined less by clear rules than by perception, trust and individual discretion.

Location matters

Location has been one of the strongest determinants of civic space during Syria’s transition. Safer areas have allowed more open engagement, while regions marked by insecurity, fear or sectarian tension have remained subdued. These differences reflect not national policy but local security conditions and administrative practice.

Before violence erupted in July, Sweida stood out as one of Syria’s most open civic environments, with residents able to organise freely in both public and private spaces. Elsewhere, insecurity proved paralysing. In Homs, kidnappings, revenge killings and sectarian tensions quickly displaced early optimism.

Local bureaucratic approaches also diverged sharply. In northwest Syria, particularly Idlib, strict oversight and approval requirements continued to constrain civic activity. Damascus followed a different path: a temporary legal vacuum, combined with the authorities’ desire to project stability, created space for civic experimentation and drew activists from across the country. By contrast, the coastal regions remained largely dormant.

Taken together, these patterns show that Syria’s civic space has been shaped far more by local dynamics than by national policy. Each region has followed its own trajectory. Geography has not merely influenced opportunity; it has set the boundaries of what is possible, what is tolerated and what is punished. Syria’s civic landscape remains as fractured and localised as its political order.

Risk tolerance

Risk tolerance has become a defining factor in how civic actors navigate the transition. With legal boundaries unclear and enforcement inconsistent, organisations have adopted sharply different strategies. More cautious groups rely on formal procedures, seeking permits and over-complying with requirements to avoid confrontation, even when approvals are delayed, revoked or denied. For them, restraint offers a measure of predictability in an uncertain environment.

Others have taken a more assertive approach, treating legal ambiguity as an opening rather than a constraint. Drawing on experience, networks, and perceived protection, these actors test the limits, bypass formal channels, or proceed without permission to expand the space available to them. Some combine both approaches, notifying authorities as they move forward unless explicitly stopped.

The result is a fragmented civic landscape shaped as much by personal risk appetite as by regulation. In the absence of clear protections, civic space has become something to be navigated, negotiated and, at times, deliberately pushed into existence.

What an initiative addresses often matters as much as where it takes place. Humanitarian activities—street clean-ups, food distribution, medical aid—generally proceed unhindered. Seen as urgent and non-contentious, they are often welcomed by authorities, filling gaps left by weak state institutions.