After a long and painful labour, Yemeni unity emerged into the world just over a quarter of a century ago, on 22 May 1990, after a tumultuous period marked by wars, revolutions, crises, moral desiccation, and deep hostility and rancour between the two regimes that ruled the country’s divided halves.

When unity finally arrived, Yemenis had got used to fear, imprisonment, and displacement, within a global context shaped by the Cold War and the stark polarisation of Soviet-aligned socialist camps and capitalist economies aligned with the West. Yet despite the agreements and preparations that preceded it, the unification of North and South Yemen unfolded with striking suddenness.

Fate seemed to hasten the realisation of this historic dream, achieved through a bold decision and a genuine national will, with the international order in flux following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The dual forces of surprise and speed left a mixed legacy, producing both gains and vulnerabilities that shaped the course of unity: from concord, to tension, and ultimately to war triggered by secessionist efforts in 1994. The consequences of that conflict continue to cast a long, tragic shadow.

Hunger drives change

From the 1940s, Yemen’s intellectual and political elites had concluded that unity was the sole means of reassembling a fragmented society, mobilising its energies, and pooling its resources. They also realised that it was the most viable framework for managing internal differences within a pluralistic political and social order.

The chance came in the late 1980s. The Soviet Union—the main ally of the socialist South, based in Aden—was already disintegrating and approaching collapse. Leftist governments all over the world that had been dependent on Soviet support suddenly found themselves exposed and uncertain, confronting the prospect of a US-dominated unipolar world. Former Southern socialist leader Ali Salem al-Beidh recently spoke with striking candour about conditions in the South at the time, the political system he once led, and what drove him toward unification.

“In South Yemen, we depended entirely on the Soviet Union,” he said. “It fed us and gave us drink. When it collapsed, we suddenly found ourselves the largest concentration of poor people in the world. We knocked on every door, but all were closed, because we were Marxists. So, we turned to our brothers in Sana’a and asked to unite with them so that we might live and secure a morsel of bread. It is true that Yemeni unity was a major popular demand, but poverty, hunger, and debts exceeding $12bn were the principal drivers of the merger.”

A meeting of minds

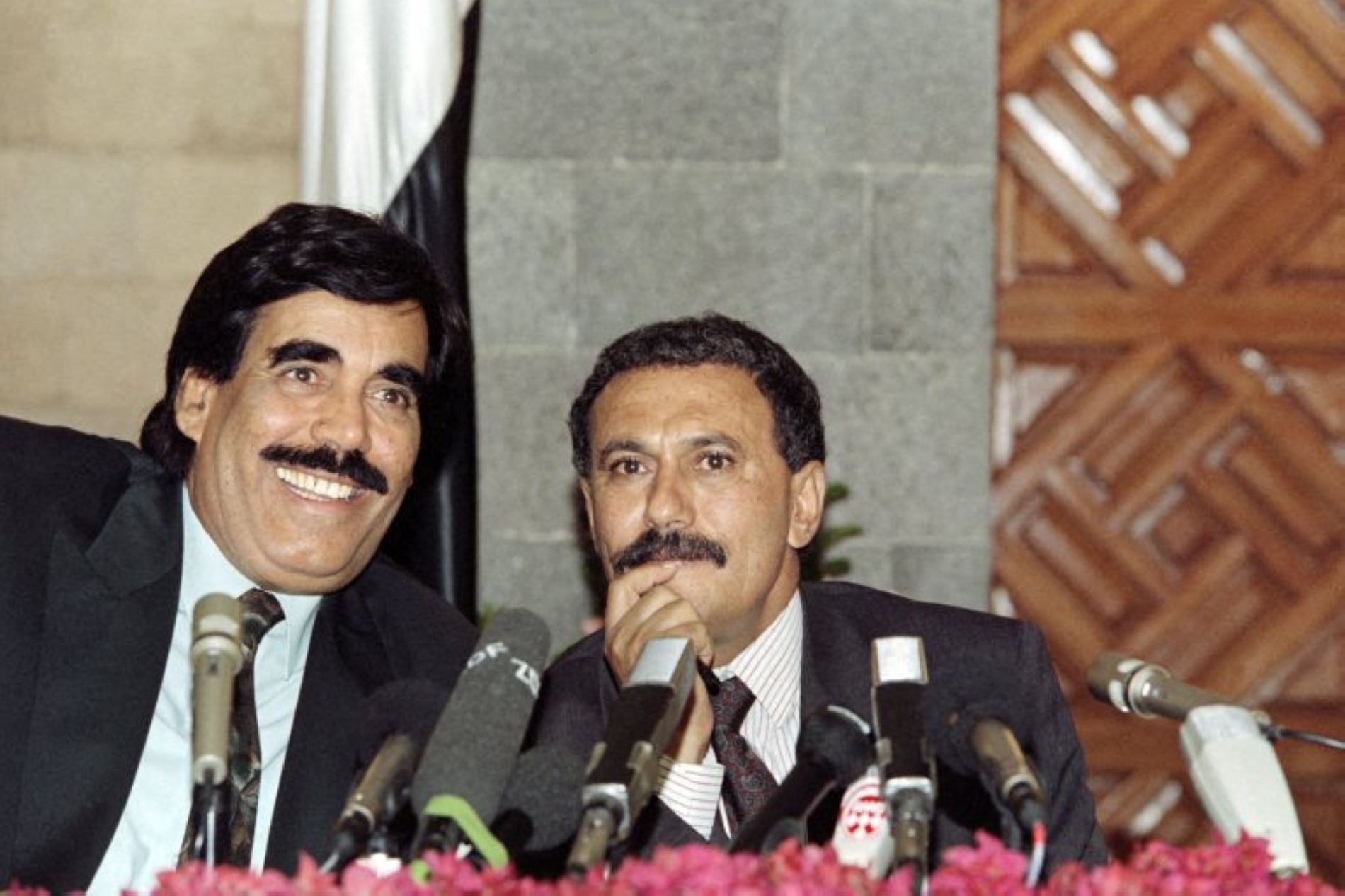

In Sana’a, President Ali Abdullah Saleh had reached a similar conclusion: that the country’s escape from accumulating crises both North and South lay in unity. Fate aligned the two men’s compasses, though few knew how it would converge. Saleh began to send signals, but they were ambiguous, even to close aides. Over time, however, they grew clearer.

Returning from an Arab Cooperation Council summit—which convened Iraq, Egypt, Jordan, and Yemen—he spoke with unusual frankness. “If our country unites, we can command greater weight within the council and benefit more from it.” Later, it emerged that Saleh was in contact with al-Beidh, seeking a clear understanding before placing the matter before their respective parties in Sana’a and Aden.

Finally, after several unity agreements signed over preceding decades by leaders of North and South Yemen, al‑Beidh and Saleh concluded the historic Aden Accord of 30 November 1989. It seemed almost miraculous. The atmosphere shifted dramatically, coinciding with the anniversary of the final British soldier’s departure from Aden in 1967.

Meeting in a tunnel

Saleh had arrived with a sizeable delegation of advisers, accompanied by more than 400 armed soldiers poised for any disruption should agreement prove elusive. At a crucial point, both leaders withdrew from deliberations with their senior aides. Al‑Beidh, taking the wheel himself, drove them towards the Gold Mohur tunnel. There, they instructed their guards to secure both entrances and prevent any passage, allowing them to negotiate privately.

No-one knows what they discussed, but the outcome soon became evident. The leaders returned to the Supreme Presidential Council building in Tawahi and summoned their ministers, instructing them to produce draft agreements for signature. To the astonishment of all, they signed an historic accord proclaiming Yemeni unity and outlining the terms of the transitional phase. It laid the groundwork for a single Yemeni state, with Saleh as president, al-Beidh as vice-president, and a draft constitution drafted years earlier, in 1981.