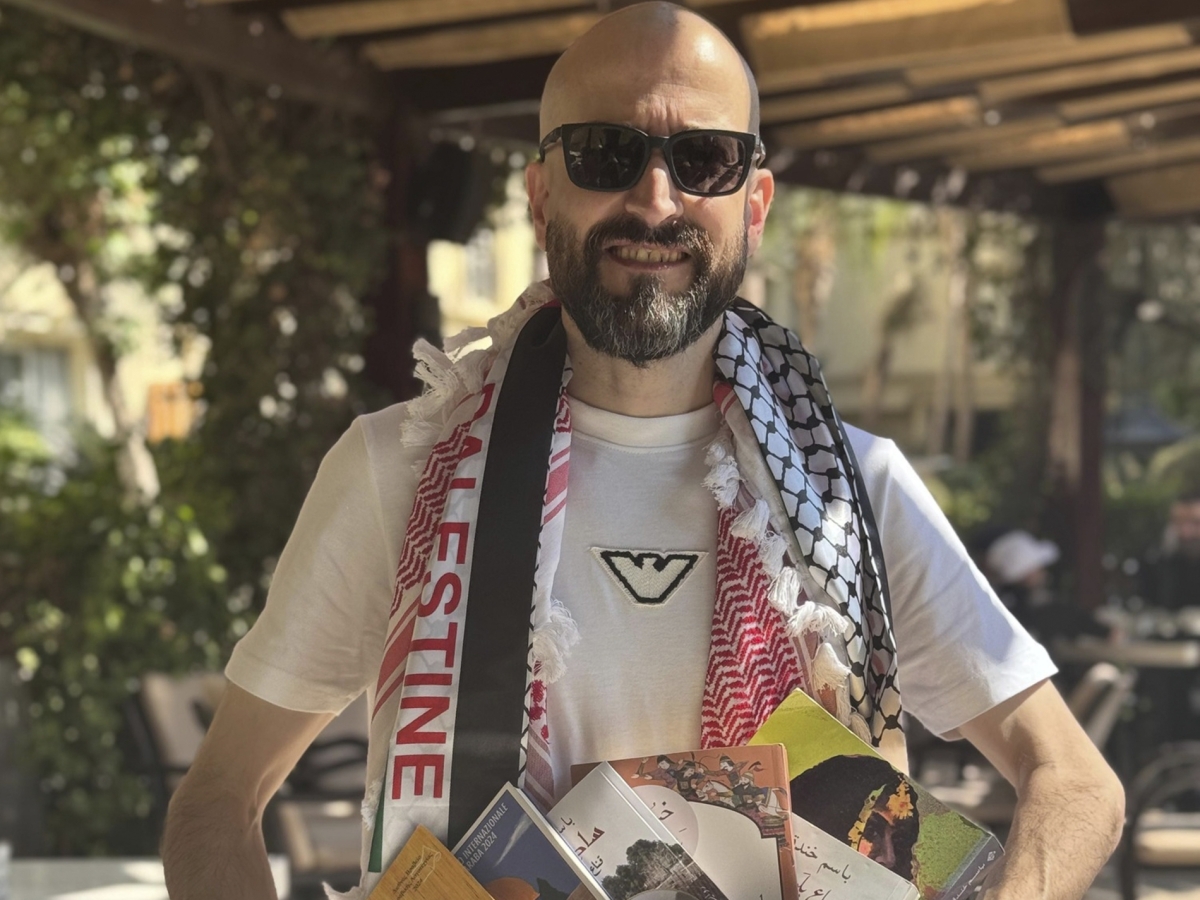

Since 2004, Palestinian novelist Basem Khandakji has languished in Israeli occupation prisons, serving three life sentences—a stark embodiment of one of the most harrowing forms of colonial subjugation.

But despite the occupier seeking to erase his presence, blot out his name from both memory and existence, Khandakji and his fellow prisoners transformed captivity into a crucible of creativity, their voices resounding with greater clarity and resonance than many who remain free.

Within the dim confines of his cell, Khandakji wielded his pen as a weapon against oppression. With deliberate craft and unwavering vision, he produced works that unsettled his jailers and stirred the conscience of Palestinian and Arab readers alike. No book passed through his hands without being devoured with fervent curiosity and reflective rigour. He read not passively but generatively, transmuting reading into a creative act, producing prose of striking depth and impact.

Born in Nablus in 1983, Khandakji’s passion for the written word began in his youth. He studied journalism and media at An-Najah National University and began writing short stories before he was arrested at age 21. But imprisonment didn't derail his intellectual or literary ambitions; he completed his university education through Al-Quds University, majoring in political science with a minor in Israeli studies.

Over the years, he built his commanding literary voice from behind prison walls. He authored two poetry collections—Rituals of the First Time (2010) and Breaths of a Nocturnal Poem (2013)—and three critically acclaimed novels: The Narcissus of Solitude (2017), The Eclipse of Badr al-Din (2019), and Breaths of a Betrayed Woman (2020).

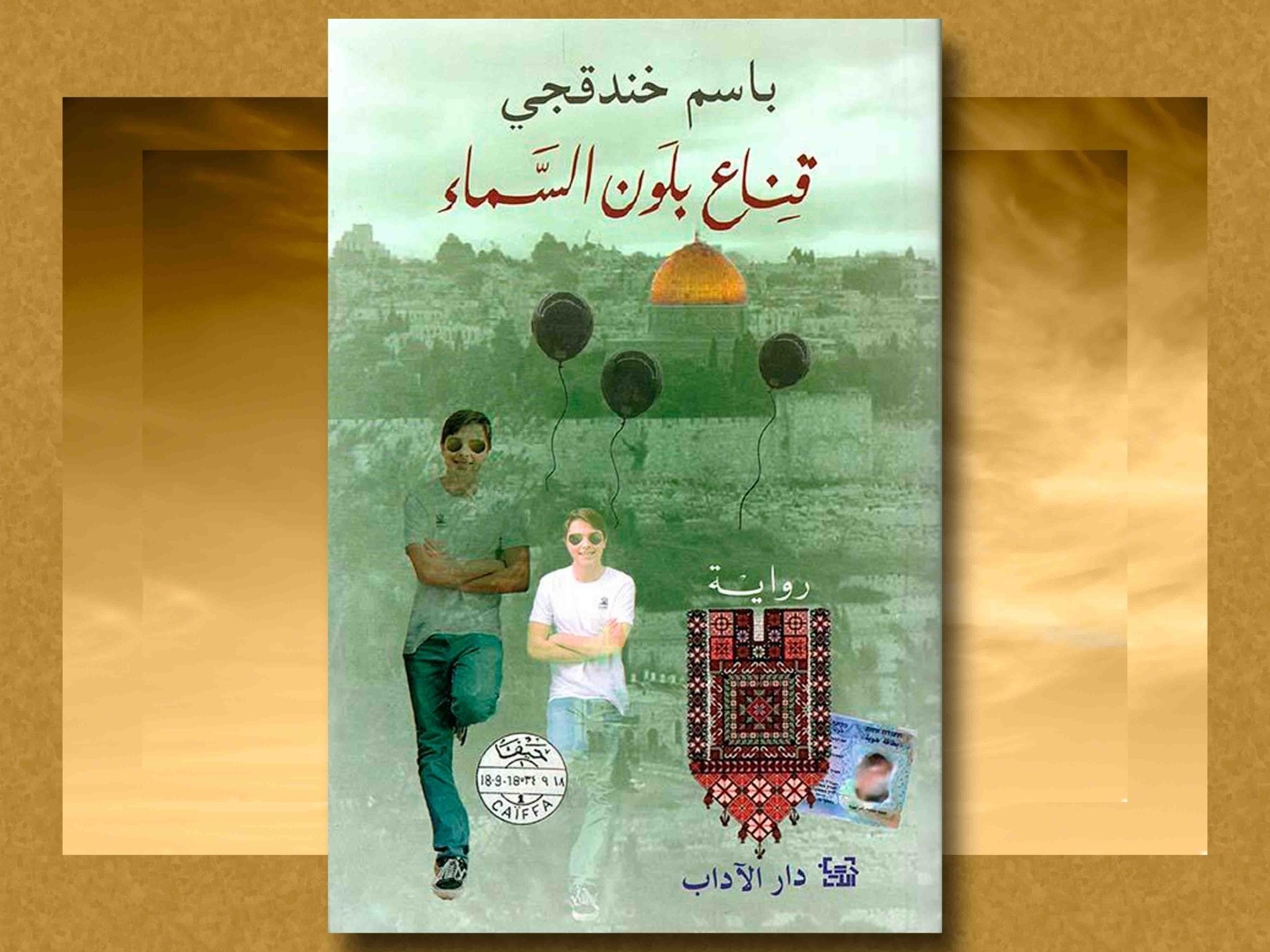

Khandakji was awarded the 2023 International Prize for Arabic Fiction (the Arabic Booker) for his novel A Mask the Colour of the Sky, announced in Abu Dhabi during the award’s 17th edition, affirming that creativity can pierce through prison bars, and that true freedom resides in the sovereignty of thought and the sanctity of the written word.

Below is our conversation in full.

When did you first gravitate towards writing novels in your literary journey?

When I realised, with growing conviction, that poetry could no longer bear the weight of the ideas and visions I sought to express. I needed a broader canvas—a more expansive form through which to articulate the Palestinian condition. I wanted to give voice to a different, dissenting register within Palestinian literature—a voice capable of illuminating the overlooked dimensions of our reality and of the wider Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

What did winning the Arabic Booker Prize mean to you?

For me, it wasn't just a literary victory—it was a form of resistance. I received the award at the height of a brutal colonial onslaught and genocidal campaign waged by the Zionist enemy against our people in Gaza. Thus, this triumph cast a spotlight not only on Palestinian suffering but on our power to confront our oppressor through literature.

Prizes offer support; they open doors and extend the Arab writer’s reach towards the global stage. I have always aspired to be read widely, to be translated into many tongues. Winning the Booker has given me the opportunity to step into that global space and carry my people’s story across borders.

And let me say this: the moment I was nominated for the Booker, the enemy launched a vicious campaign of incitement against me. Its aim was to strip me of my humanity, to send a message to the world that a Palestinian is incapable of authorship. Yet, despite their efforts, this victory unsettled the colonial and racist cultural machinery of the occupier. It was a rupture they could neither predict nor contain.

Turning to the novel itself, and to Nour al-Shahadi, the deeply complex and problematic protagonist. How did you construct this character?

In all my novels, I am drawn not to the ready-made hero, nor to characters who offer facile answers, but to those riddled with contradiction, figures who unsettle, provoke, and can't be easily defined. Nour is no exception. At times, I found myself drawn to him, even empathising with his inner turmoil, but I also held him to account. Through him, I sought to show the hidden recesses of the Israeli narrative—those shadowed corners rarely exposed in Palestinian literature.

To do so, I employed a range of techniques, chief among them the insights of Frantz Fanon, particularly his seminal essay Black Skin, White Masks. Nour attempts—by wearing the mask of 'the other', i.e. its features, its language, its gaze—to penetrate the epistemic interior of that 'other'. He ventures into a realm from which Palestinians have long been barred: the cognitive and ideological architecture through which the coloniser perceives the colonised.

By wearing the mask of the Israeli, Nour is able to see the Palestinian through Israeli eyes—something never before tried in our literature, which usually leans on a static, monolithic image of the enemy, just as Israeli literature has done with the Palestinian. Nour’s journey is an attempt to strip away these masks, even as he dons one himself. It is a radical act of narrative infiltration—a bold experiment designed to reveal that, at its core, the struggle is one of identity.