Two years of war in Gaza have left behind more than shattered buildings—they have torn through the very fabric of cultural life, dismantling artistic institutions and severing the threads of dialogue between writers and artists. A fractured reality sits in their place. What role now for culture and creativity at a time so steeped in loss?

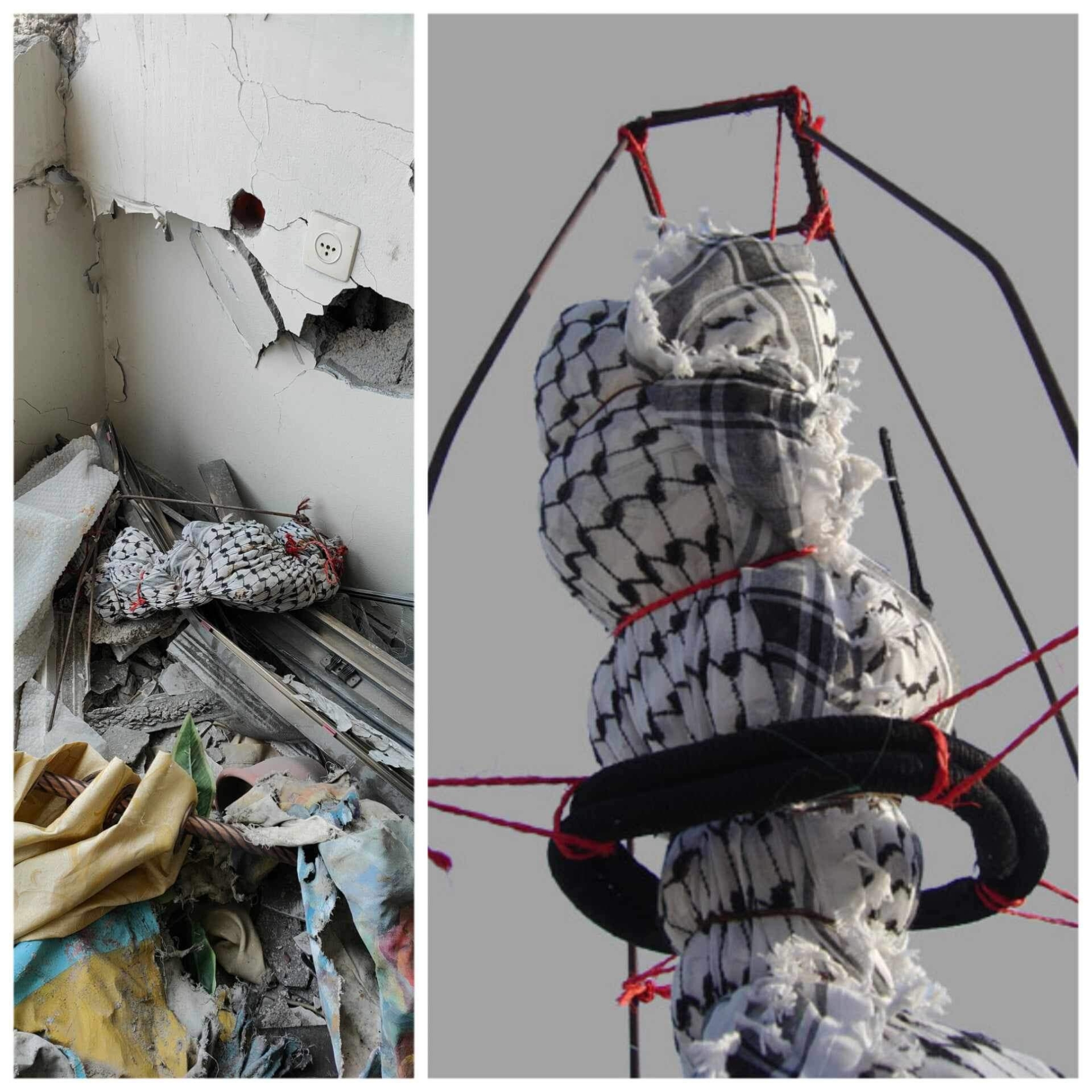

Mahmoud Al-Sha'er, of Gallery and Magazine 28, says his institution's destruction is deeper than the physical loss. The gallery was "reduced to rubble," he says, adding that this was an archive of modern Palestinian memory—a locus of consciousness, and a breathing space for the community. "Culture is a necessity," he insists. "We must continue to write, always. Healing begins with the act of writing."

Al-Sha'er now finds himself alone with the pen, stripped of the collective energy that once animated his work. "The war returned me to myself, granting me solitude for personal writing after years of collaborative creation." What remains of Gaza's cultural landscape, he says, is ash that must be reshaped. "We must reclaim the tools of collective expression. But first, we need safety. A society cannot revive its audience without a sense of security, and without an audience, there can be no cultural life."

For Al-Sha'er, creativity is no longer a solitary endeavour but a matter of infrastructure and of the conditions that allow it to exist. "We need to institutionalise individual efforts, to transmute tragedy into art," he says. "That requires substantial funding. The occupation has institutions; we have only memory."

Visual artist Lamees Al-Sharif remembers her torn canvases. Before the war, she was part of Atelier Gaza, a collective of female painters housed in the Young Men's Christian Association, which is now a shelter for the displaced. "People entered and tore the paintings apart, using the wood to light fires for cooking. It wasn't an attack on art; it was a way to survive." Art cannot feed the hungry, she acknowledges, but it nevertheless thinks that "cultural work is a vessel for societal survival, just like education".

She speaks with quiet anguish of the chasm between the need for bread and the yearning for beauty. "A person living in a tent, gripped by insecurity and unable to secure a meal, how can culture shield him from his suffering?" Still, she offers a crucial distinction. "Our tragedy is not a commodity. Those who render their pain in aesthetic form are not embellishing; they are reaching out to life with the memory of beauty."

Al-Sharif believes that there are truths too vast for art to contain, yet cultural practice remains a form of experimentation—a way to navigate the catastrophe. "While working with children during the war, I heard testimonies from those who had endured displacement, encountered soldiers, tasted fear and death, and stumbled upon decomposing bodies. How can culture help heal such trauma? That is the essence of Gaza's future cultural work."

Her new paintings are not decorative; they are declarations of survival. "What I created during the war was deeply personal—not beautiful, not communal. I needed to feel that I still existed." The prospect of returning to collective cultural work feels distant, almost unreachable, but she does not close the door. "Perhaps in the near future, with small steps, in a new space, with modest funding, and a quiet faith that life's wheel has begun to turn."

Art as dialogue

Visual artist and filmmaker Basel Al-Maqousi writes as though painting with words. "I borrow the eyes of those ascending to the heavens to sketch Gaza, leaving a space in memory for what once was," he says, a poetic invocation that is no mere metaphor but a testament to the loss and longing that shape his creative practice. Al-Maqousi participated in the film From Ground Zero, screened at the Cannes Film Festival, and is a founding member of the Eltiqa Gallery for Contemporary Art, which was destroyed during the war.

For him, art is no static archive but a living dialogue with the world. "The artist does not document events in the literal sense but addresses the world through them artistically. Many cannot bear to witness images of atrocity, but they can receive them through music, theatre, novels and poetry." In the absence of physical venues, Al-Maqousi sees the digital realm as a surrogate stage.

"Today, we can exhibit our work through social media until the time comes to rebuild our galleries and theatres. Creativity has never ceased, despite all the bans and suppression." He says art is "the soft hand of resistance", and the intellectual "the first to resist and the last to fall". When he speaks of Gaza's cultural future, his words are tinged with sorrow and resolve. "Rebuilding Gaza will not be limited to streets and schools; it must encompass every facet of life. Culture will have a vital share in that renewal."