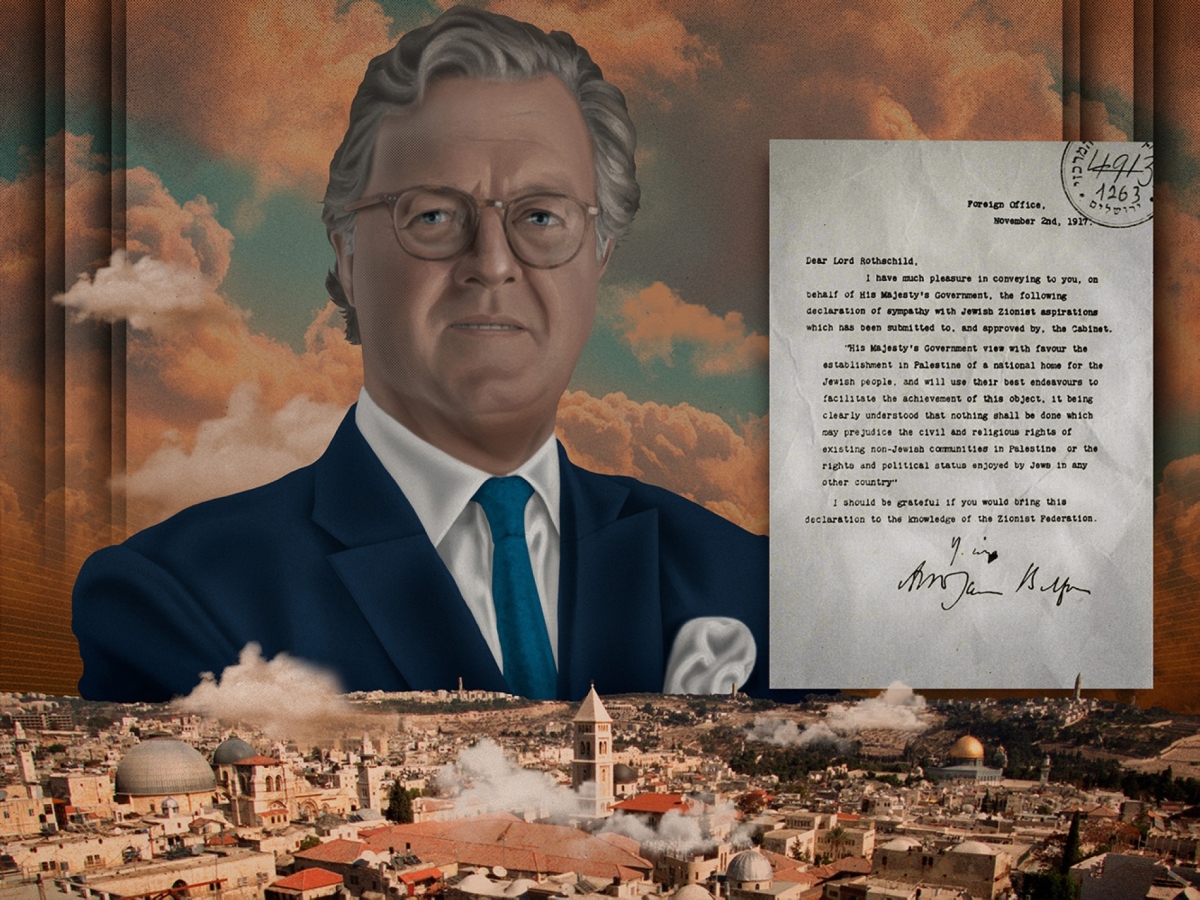

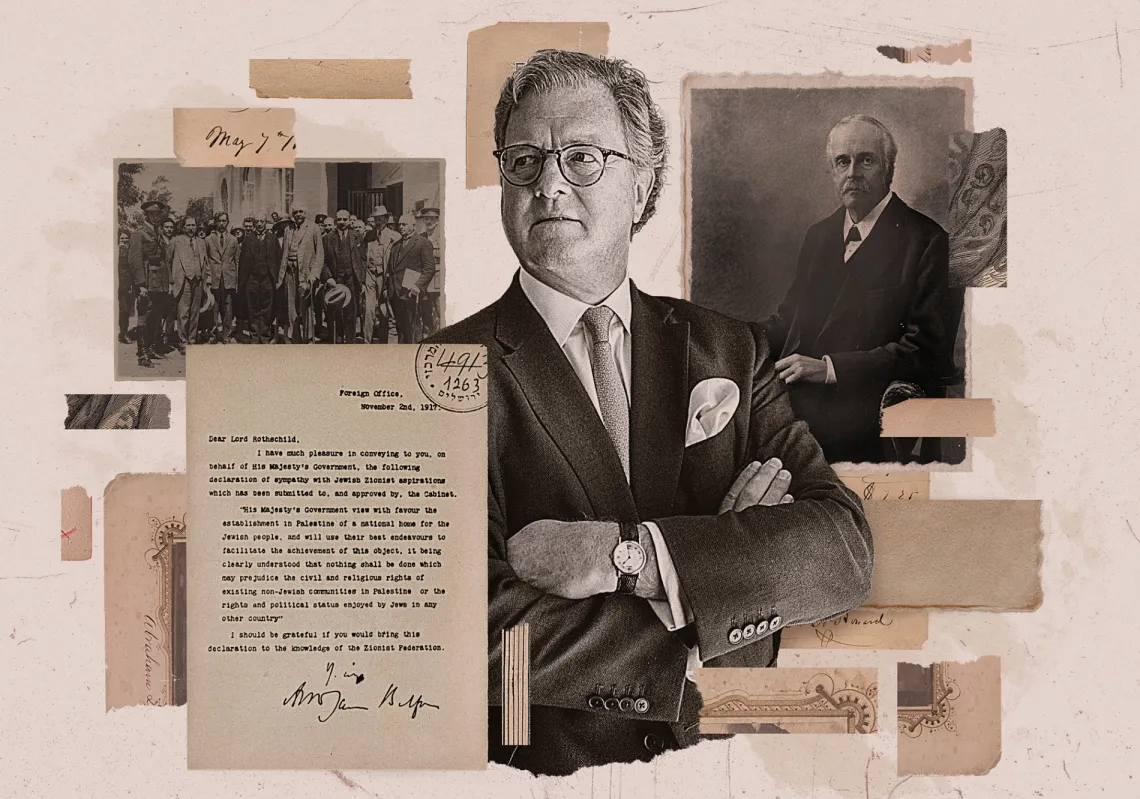

In 1917, the British Foreign Secretary Lord Balfour declared that the government "views with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people". He said Britain would help facilitate it, on the condition "that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country".

Balfour was expressing not just sympathy but a firm commitment to the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine. The language is unambiguous—it is a declaration of intent, reinforced by the pledge to exert the UK's "best endeavours". Yet Judaism is not a nationality; it's a religion. And no religion constitutes a nation, not even Christianity, which is practised by billions globally. Religion transcends borders and ethnicities; it does not define a country.

The 'Balfour Declaration' repeatedly refers to Palestine as a geographical entity, yet conspicuously omits any mention of the Palestinian people, rendering them invisible or incidental residents, not a people with historical presence and political agency. In doing so, it perpetuates the myth of "a land without a people," limiting Palestinians' rights to civil and religious protections while withholding recognition of their national status.

Rendered invisible

At the time of the Declaration, Jews constituted 3% of Palestine's population. They were not a national group, but religious communities—similar to Jewish populations in Syria, Iraq, Egypt, Morocco, Libya and other Arab countries. These communities lived in harmony with their surroundings and were often integrated as citizens, many holding public office. They were not representatives of a separate nation.

In an interview with Al Majalla, Balfour's grandnephew, Lord Roderick, offered a reading that reveals how history can be misremembered. He appeared keen to absolve his granduncle of the calamity that befell the Palestinian people—and, by extension, the wider Arab and Muslim worlds. His interpretation of his grand uncle's declaration overlooked or sidestepped the existence of an indigenous population inhabiting the land delineated by the Sykes-Picot Agreement.

This 20,000 sq.km. territory extended from the northern slopes of Mount Amel in Lebanon to the international frontier of Egypt in Sinai, encompassing a constellation of historic cities. In the north stood Safed, a long-established Palestinian city, alongside the Galilee and its northernmost reaches. Along the Mediterranean coast lay Jaffa and Wadi al-Rabi'. Jerusalem, a spiritual and civilisational beacon, housed both the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Tiberias sat on the southwestern shore of its eponymous lake, while the West Bank was home to ancient cities such as Nablus, Jenin, Ramallah, Lod and Birzeit. Jericho—widely regarded as the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world—lay nearby, as did the Dead Sea, Gaza, Al-Qastal, Beisan, and the once-thriving port of Haifa, a major maritime hub for the wider Arab region prior to its occupation.

Palestine was deeply integrated into regional infrastructure. The railway connecting Syria to Haifa extended through Palestinian territory and reached Al-Arish, Alexandria, and Cairo, eventually stretching as far as Medina. This Ottoman-era network reflected the region's historical connectivity and strategic value.

Hejaz Railway, Beersheba, Palestine, 1900s (Hicaz Demiryolu, Birüssebi, Filistin) pic.twitter.com/d4uJ9ZmJmU

— Ottoman Imperial Archives (@OttomanArchive) June 18, 2017

Seeds of change

Lord Roderick Balfour failed to acknowledge that the 1917 Balfour Declaration was issued in the aftermath of the Sykes-Picot Agreement and the involvement of the Russian consul in the dismemberment of the Levant—a region bound by shared people, culture, geography, landscape and familial ties. It was not (as is so often claimed) a philanthropic gesture toward Judaism as a religion. Rather, it served the imperial ambitions of Britain at a time when much of Europe harboured entrenched animosity toward its Jewish communities.

In countries such as Britain and Russia, Jews were prohibited from owning land, denied access to housing and public employment, and often confined to roles in financial services and lending. In this milieu, the Rothschild family's banking empire rose to prominence, funding the Jewish National Fund and exerting pressure on European governments—particularly the British government—to issue a declaration in support of the Zionist cause.

Gaining momentum since the 1897 Basel Conference under Theodor Herzl, Zionism called for a homeland for dispersed Jewish communities. Various locations were proposed—Uganda, northern Iraq, and Argentina—but it was British colonial policy that ultimately adopted the idea, aligning it with the strategic vision outlined in the 1907 Campbell Document, formulated during the premiership of Henry Campbell-Bannerman. This document laid out a colonial strategy designed to preserve Western hegemony.