In recent years, influencers have used their prominent presence on digital platforms to generate buzz, shape public opinion, and influence not only consumption habits but also cultural preferences. In the Arab world, their ‘influence’ is broader, because they increasingly shape values and social norms.

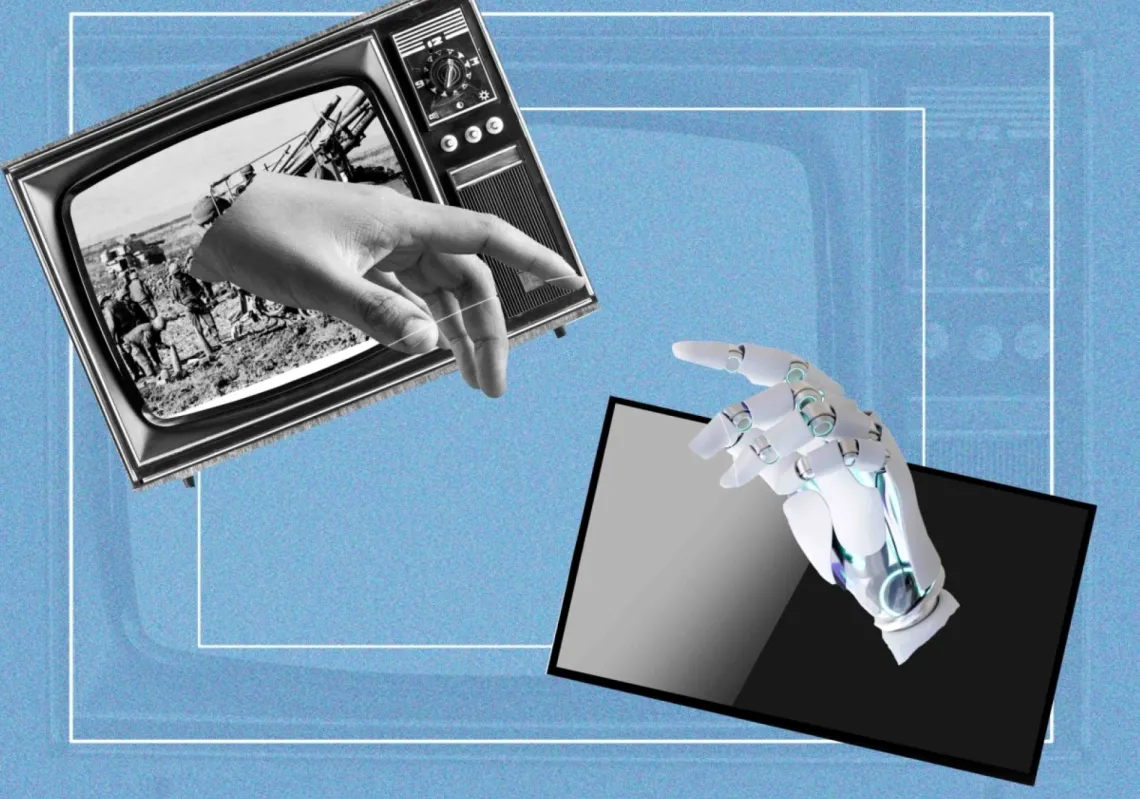

Originally rooted in marketing, the term ‘influencer’ referred to those capable of swaying consumer behaviour. The rise of influencers is now seen as a result of what could be called ‘attention capitalism’, whereby the individual becomes both the online platform and the commodity. Their influence stems more from virtual interactions (follower counts, viewership, etc.) than from intellectual or artistic credibility. This is the commodification of the self and the theatricalisation of everyday life. Gestures and emotions are recordable, consumable, and susceptible to influence.

Image management

Where cultural icons were once revered for their intellectual, artistic, or moral achievements, influence today is increasingly defined by image curation and continuous visibility, even when the content lacks depth and substance. In today’s world, is influence even genuine, or merely the outcome of algorithmically-driven attention? Some who consider this think there has been a hollowing-out of symbolic authority.

Influence is now measured in metrics (such as online ‘followers’ or ‘likes’) rather than in the rigour, originality, or weight of thought. More traditional figures of impact—such as intellectuals, politicians, or trade unionists—were embedded within a broader social structure that lent coherence and permanence.

The intellectual, for instance, derives influence from symbolic capital such as knowledge, thought, creativity, dedication, or ethical clarity, qualities that confer legitimacy independently of audience approval. The politician’s influence, likewise, is rooted in the authority of representation, while the trade unionist’s authority comes from representing a class, profession, or movement. All three are tethered to institutions that bestow structure and legitimacy, whereas the influencer derives legitimacy solely from follower count, a solitary pursuit for a marketable self-image.

Discourse evolution

The relationship between traditional figures of impact and their audiences was inherently critical. Intellectuals addressed the public with the intention of elevating discourse towards broader, more reflective horizons. Politicians presented agendas that invited scrutiny and accountability, while trade unionists negotiated in pursuit of collective aims and concrete improvements.

The influencer’s relationship, however, is reciprocal rather than critical. Entertaining or provocative content is exchanged for attention in a dynamic absent of social contract, representation, or accountability. In The Transparency Society, the philosopher Byung-Chul Han says, “Digital communication eliminates all forms of negativity. It is based on consensus, conformity, and positivity.”

In contrast to the prevailing glorification of “positivity” in contemporary discourse, Han critiques this communication model for eliminating negativity. The problem, he argues, is no longer repression but an excess of freedom, one that drives individuals to perform, display, and commodify themselves. This unrelenting positivity turns toxic, dissolving the contrasts essential to critical thought and producing individuals who are drained, hollowed out, and deprived of meaning.

The intellectual seeks meaning or a cause, whether that be justice, freedom, or enlightenment. Likewise, politicians aim to change policy or secure power, and unionists fight to defend rights or improve working conditions. Yet the influencer seeks only ‘attention capital’, a resource that can be converted into fame or financial gain. Influence becomes a goal unto itself, rather than a means to a higher purpose.

Fragmented space

Intellectuals, politicians, and trade unionists have traditionally operated within a public sphere founded on a relatively rational mode of discourse, through newspapers, forums, parties, and associations. Influencers, by contrast, navigate a fragmented virtual space shaped by algorithms, where fleeting impressions outweigh reasoned debate, emotional provocation can be more effective than logical persuasion, and influence is prioritised over substantive engagement or meaningful action.

The authority of the intellectual or the politician stems from a recognised social role and a commitment to a broader public project, but the influencer’s power is the product of an individualised process of self-branding. They trade in the transient, fragile nature of contemporary influence, unlike intellectuals or political figures, whose legacies can endure for decades.

Influencers source their subject matter or content in everyday occurrences, sometimes depicted as their daily routine, but in fact it is rarely born of discovery or verification. More often, it comes from their peers, rumours, comments, leaks, and reactions. Rather than disseminating verified information or addressing wider public concerns, much of this content is orientated inward, towards the influencer ecosystem itself.