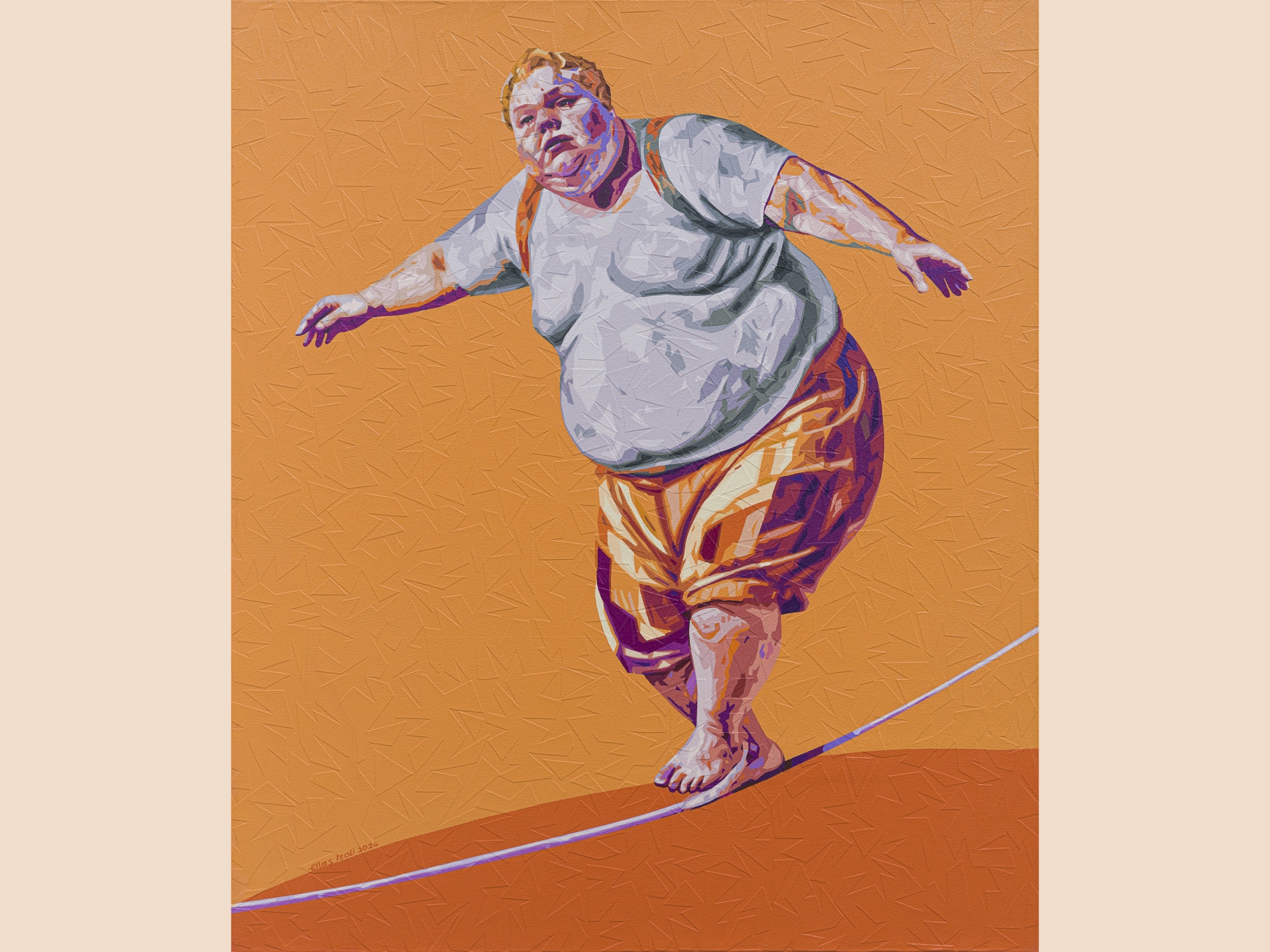

In earlier works, the artist conveyed the anguish of war and the Syrian conflict, particularly through depictions of children caught in loneliness and suffering. Here, circus performers are forced to invent their own equilibrium, "to seek it in every detail of their being, even when uncertain whether they possess the freedom to choose".

He says his visual style has not changed in terms of form, but during his time away from painting, he says he "was deeply affected by the escalating tragedies and violent conflicts around me". A serious health crisis also shifted his outlook profoundly. This is evidenced in his shift from digital textures and cubist lines, where geometry functions more as texture than form, to clinical outlines in the backgrounds of his new work.

These stark elements create a chilling effect, a stylistic change that feels like a natural progression from his earlier work, alongside Izoli's skilled and intuitive use of colour to support his themes. The metallic blue that dominates many figures in this series recalls earlier exhibitions, particularly Tawasul (Continuity), a tribute to the late Syrian artist Louay Kayyali.

Out with the soft

In From the Inside Out, Izoli continues to apply colour with striking intentionality. His current palette is dominated by the opposing hues of orange and blue, a contrast that produces a visual tension both captivating and unsettling, at times blended into a brown shade evocative of burnt clay that casts dense, opaque shadows. This is a deliberate choice to reject the soft or the vague in favour of a chromatic clash that echoes the anxiety, fatigue, and isolation felt by his subjects.

One painting that stands out is of a performer standing behind the circus curtain, confronting us with a gaze that hovers between indifference and hostility. Despite the unsettling nature of these expressions, Izoli evokes a profound empathy for his subjects.

Another striking piece features a rotund man with childlike, petulant features trying to—or perhaps refusing to—mount a horse far smaller than himself. The animal stands beside him like a toy in an oppressive blue void. Surrounding this troubled man-child is a host of similarly juvenile-faced figures performing acrobatic feats, none of whom appear remotely content.

In earlier works, Izoli depicted children weighed down by sorrow that drained all joy from their play, showing how toy horses and balls were no longer sources of amusement. Here, his characters retained a dysfunctional bond with objects and actions. Whether balancing on oversized spheres or engaging in movements with no hint of pleasure, they seem confined to roles not of their choosing.

Lightness and weight

In many of Izoli's paintings, the blue turns into a deep purple, which raises the question of how works so emotionally charged can appear so cold and devoid of life. On one level, the artist evokes the sorrowful figures of Spanish painter Pablo Picasso's 'blue period,' which in turn recalls the work of Louay Kayyali.

In Izoli's hands, blue becomes a force of pressure, not colour. Kayyali's almost weightless figures are replaced by forms that appear unnaturally swollen, corpulent bodies devoid of joy, yet they continue to perform acrobatics, posing questions about the nature of light and the meaning of weight.

Each figure tries to reconcile reality with imagination, longing with loss, anxiety with indifference. For Izoli, anxiety is a basic condition of life; it is not the fear of falling, but the fear of having to maintain balance, which arises from the knowledge that we alone are responsible for our choices. Anxiety, therefore, is the cost of freedom and the motive to act. There is no good reason to avoid facing what must be faced. There is no path but forward.

Izoli's characters seem to understand that. Their movements are repetitive and mechanical. Each action appears to exert a quiet, physical strain. Within this strange display, the performers continue their acts despite being overwhelmed by disappointment.

What seems like lightness is heavily laden with emotional weight. In one painting, a performer walks a tightrope while bearing a suitcase on his back. Izoli does not depict these corpulent, half-naked figures in the endearing manner of Fernando Botero, with his indulgent women. Instead, he uses them to expose the existential tension between lightness and weight.

In the words of Milan Kundera, author of The Unbearable Lightness of Being: "Whoever aims for something higher must expect vertigo one day. What is vertigo? Not the fear of falling. No, vertigo is something else: the voice of the emptiness below, that lures and seduces us—the desire to fall, against which we defend ourselves in dread."