During the 17th and 18th century, European philosophers and political scientists used the ancient Latin term casus belli to define a case for waging war.

Modern international law recognises three lawful justifications for war: if it is waged in self-defence, if it is waged in defence of an allied country bonded to by treaty, and finally, if it is approved by the United Nations.

In the early 1980s, and in the context of the Middle East, US Secretary of State Alexander Haig adopted less sophisticated terminology. He said that under no circumstances would Israel be allowed to invade Lebanon “without a pretext.”

The word “pretext” was far easier to understand — and promote — than casus belli. Not all countries, however, make sure they find a pretext for declaring war on another country.

In many cases, wars are packaged as straightforward expansionism and territorial greed, like Adolf Hitler’s 1939 invasion of Poland or Saddam Hussein’s 1990 annexation of Kuwait.

Erdogan’s Operation Claw Sword

On 20 November 2022, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan joined the list of world leaders who took the trouble to find a pretext when he launched Operation Claw Sword against the Kurds of northern Syria.

His casus belli came in the form of a terrorist attack carried out in Istanbul’s world-famous Istiklal Avenue on 13 November, which killed six people and wounded 21.

Turkish security officials immediately blamed it on Kurdish separatists operating from Syria. Warplanes were sent to bomb the separatists with the aim of forcing them either into submission or surrender.

It was actioning that Erdogan had been longing for but had been prevented from taking by his Iranian and Russian allies before the Istiklal bombing. He found in the attack the pretext he needed to act.

Turkiye targeted US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) bases, along with ammunition depots, tunnels, and roads. All this was justified by article 51 of the UN Charter: Turkey’s right to self-defence.

Here’s a look at similar “pretexts” used by other leaders, long before Erdogan.

The 1914 murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

On 28 June 1914, 19-year-old Gavrilo Princip killed the Archduke of the Austro-Hungarian Empire Franz Ferdinand, firing a pistol at the convertible car carrying the heir to the throne during a visit to Sarajevo.

The Serbian authorities denied Austrian claims that they had armed and trained the young assassin. Austria used this response as a casus belli to declare war on Serbia, igniting what became World War I.

It is probably the most famous of all “pretexts” in modern world history. Princip was subsequently spared the death penalty because of his age, sentenced instead to 20 years in prison at the Terezin fortress (now in the Czech Republic).

He died from tuberculosis in April 1918, before World War I came to end.

The Syrian telegram of 1920

On 14 July 1920, Syria’s new king, Faisal I, sent a congratulatory telegram to the French government marking Bastille Day. He received two letters in reply. The first was cordial, thanking him for his “kind message.”

The second was an ultimatum signed by France’s High Commissioner to the Levant, General Henri Gouraud. It demanded that Faisal disband his army, arrest anti-French Syrians, and accept the French Mandate stipulated by the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916. Gouraud gave Faisal a deadline to comply, set at midnight on 17 July 1920.

Faisal accepted all of the demands due to concern over the weakness of his army. But Gouraud said that he had been expecting “compliance” by the deadline and not just acceptance.

Another deadline was fixed, ending at midnight on 20 July. The Syrian government complied, pledging to formally disband its army. It put that pledge in writing in a telegram sent to Gouraud at 5:02 PM on 20 July. But Gouraud claimed that the telegram reached him past the deadline and ordered his troops to march on Damascus.

The Syrian and French armies clashed at the Battle of Maysaloun on 24 July. Syrian troops were massacred, Faisal was dethroned, and the French Mandate was imposed on Syria. The delayed telegram was France’s casus belli to invade and occupy Damascus.

Gamal Abdul Nasser and the Straits of Tiran

After the Suez War of 1956, Egypt agreed to the stationing of a UN peacekeeping force in the Sinai, known as UNEF (United Nations Emergency Force).

In 1967 President Gamal Abdul Nasser decided to withdraw UNEF forces and close the Straits of Tiran to all shipments bound for Israel, blocking the port of Eilat at the northern end of the Gulf of Aqaba.

He hoped this would stop the Israelis from attacking Syria — a country to which Nasser was emotionally attached, having been its president between 1958 and 1961. But more importantly, Nasser felt he had to honour a mutual defence pact with Syria.

Israel responded that it would consider the closing the Straits of Tiran as declaration of war, a response that Nasser ignored.

But the closure was used as Israel’s casus belli for the 1967 war.

Several nations argued at the UN General Assembly immediately after the conflict that even if international law gave Israel such rites of passage, it was not entitled to attack Egypt to assert them because the closure was not an "armed attack" as defined by Article 51 of the UN Charter.

International law professor John Quigley argued that Israel would only be entitled to use such force as would be necessary to secure of passage. Israel’s Defence Minister Menachem Begin would later say: "The Egyptian army concentrations in the Sinai approaches do not prove that Nasser was really about to attack us. We must be honest with ourselves. We decided to attack him."

The 1982 assassination attempt on Shlomo Argov

On 3 June 1982, the Palestinian militant group The Fateh Revolutionary Council carried out a failed assassination attempt on Israeli’s ambassador to London Shlomo Argov.

It was carried out on the orders of Sabri al-Banna, also known as Abu Nidal, a sworn enemy of Yasser Arafat, chairman of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO).

Argov survived but was left paralysed and blind until his death in 2003. But his case was used as a casus belli to justify the invasion of Lebanon, with the declared intent of crushing Arafat and the PLO.

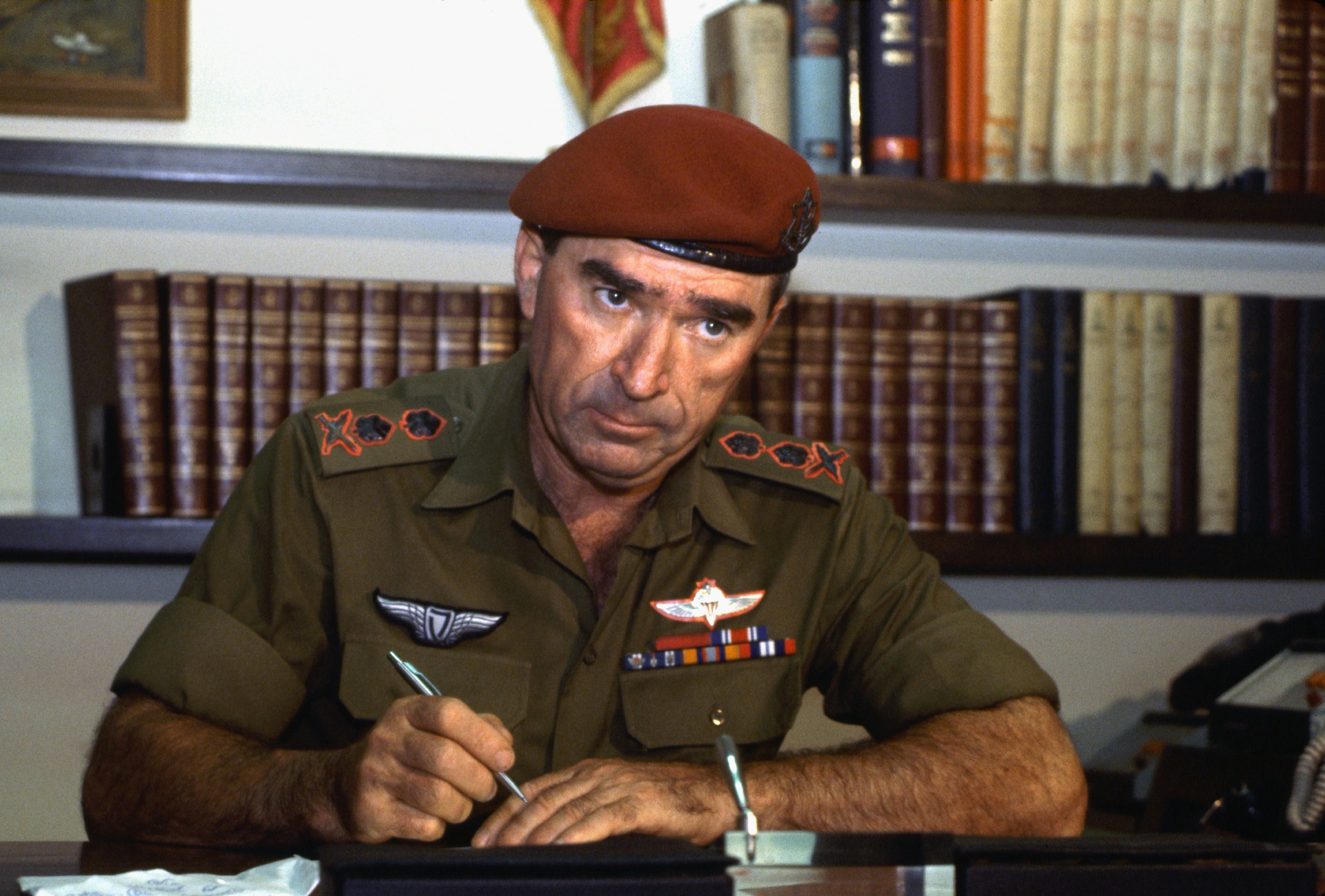

At an Israeli cabinet meeting, the Israel Defence Forces’ chief-of-staff, Rafael Eitan, was reminded that the PLO had nothing to do with Argov’s assassination, and that it was the work of Abu Nidal.

He famously replied: “Abu Nidal, Abu Shmidal, I don’t care. We will screw the PLO.” On 6 June, Operation Peace of Galilee was launched, leading to the invasion and occupation of Beirut.