[/caption]

[/caption]

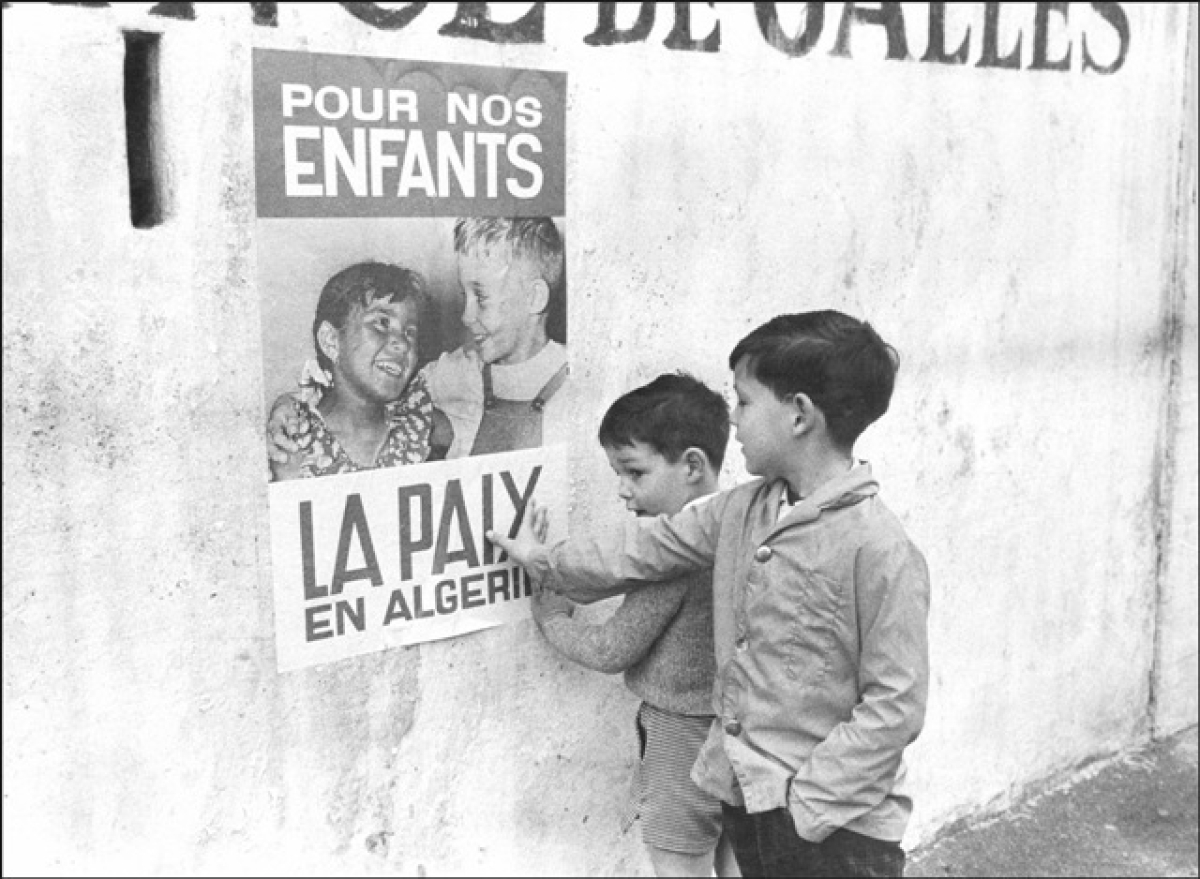

2012 officially marks the 50th anniversary of Algerian independence from France. In recent months, a number of media outlets and historians have attracted significant attention to this milestone. At a political level however, French president Nicolas Sarkozy and his Algerian counterpart Abdelaziz Bouteflika have chosen to remain cautiously silent about the issue. This comes as no surprise considering that both countries are in the midst of important electoral periods, and evoking the painful and unresolved differences of the past would likely prove disadvantageous. Furthermore, following the recent revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, president Bouteflika knows he must play his cards right in order to safeguard his regime from potential instability.

The historical relationship between the two countries is a complicated one. France invaded Algeria in 1830 and controlled it until March 1962, when the the French delegation for Algerian affairs and the provisional FLN (National Liberation Front) government signed the Evian Accords, officially establishing a cease fire ending a brutal seven and half year war, and paving the way for a successful independence referendum three and half months later. This was an implicit recognition by the French government (led by De Gaulle) of the FLN and the newly-created Algerian state.

[inset_left]The 2005 banlieue riots were the culmination of decades of frustration and resistance to inequality and institutional discrimination.[/inset_left]

Independence following 132 years of colonial rule was highly traumatic for both sides. In the case of France, unlike other colonies that were merely overseas territories or protectorates, from 1848 until independence, the entire Mediterranean region of Algeria was legally and administratively part of metropolitan France. Thus, rather than a movement for independence, it was viewed by many French elites as a war of succession. France´s defeat in Algeria contributed to its postwar crisis of identity as it called into question the legacy and credibility of its colonial civilizing mission (mission civilisatrice), which had always been justified through the humanistic values of the Enlightenment.

Following Algerian independence in 1962, most of the over one million pieds-noirs (French citizens who lived in French Algeria before independence and opposed Algerian nationalist groups), which accounted for approximately 10% of the Algerian population, were evacuated to France. Psychologically, their condition was complex: many had difficulty integrating into a mainland French culture from which they were disconnected, many longed for the lifestyle they had lived in Algeria, and as a collectivity, they were often criticized by the left for exploiting Algerian Muslims and causing the war. In addition, during the period of rapid industrialization from 1945-1973 (Les Trente Glorieuses), over 700,000 Algerian immigrants settled in France. Many of these were Harkis (Muslim Algerians who fought on the side of the French against Algerian nationalists) who, despite their loyalty to France, were unwanted and placed in isolated camps upon arrival; those who attempted to return to Algeria were rejected as traitors and often faced violence or even death.

Once in mainland France, many first-generation Algerian immigrants faced discrimination in employment and housing, violence (e.g. 17 October 1961 and the 1962 Charonne Metro Massacre), and deportation scares (e.g. the attempt by former French president Giscard d´Estaing to deport Algerians in mass in the late 1970s). In the early 1980s, the second generation emerged. Born and educated in France, they demanded more than their parents and attempted to confront discrimination through resistance. Since that time, due to the influence of the FN (the National Front) on mainstream politics, immigrant descendants have increasingly become politicized pawns of electoral politics. Over the past decade, former interior minister and current French president Nicolas Sarkozy has frequently scapegoated them in his efforts to sway votes away from the far-right.

The 2005 banlieue riots were the culmination of decades of frustration and resistance to inequality and institutional discrimination. In their aftermath, testing has been carried out by different individuals and organizations that clearly highlights the persistence of colonial memory, and in particular France´s historical trauma with Algeria. Job applicants of North African origin are three to five times less likely to be called for an interview than applicants of French origin when they have equal qualifications, and unemployment for university graduates of North African origin is five times higher than for those of French descent. Discrimination is also widespread in the criminal justice system, where a disproportionate number of identity checks (contrôles aux farciès) target minority youth.

Until postcolonial immigration occured, France´s republican model of integration had always been considered highly succesful in transforming immigrant descendants into “Frenchmen”, particularly by means of its schools and military service. Today, that is no longer the case. Not only have its institutions largely failed to ensure fraternity (fraternité) and equality (egalité), descendants of North African Muslims are at the heart of party politics and are widely seen in French society as inassimilable.

In the case of Algeria, since independence, it has, in many ways, made significant strides towards self-sufficiency. The nationalization of foreign oil holdings in 1971, the halting of all emigration to France in 1973 and its current strategic geopolitical role in North Africa are all good examples. However, like all ex-colonies, the legacy of its past remains deeply embedded in its present. The army (known as Le Pouvoir) maintains a stronghold on virtually all key aspects of society, education is poor, unemployment is high, corruption is widespread, and foreign domination in certain industries is inescapable. According to the 2011 UNDP Human Development Index, a comparative measure of life expectancy, education, literacy, education, and standard of living, Algeria is ranked 96 out of 187 countries.

Today, based on their long hybrid history, unsurprisingly, France and Algeria have strong commercial ties. Algeria is France´s leading trade partner in Africa and France is Algeria´s leading supplier. Furthermore, at a political level, both countries have a genuine desire to move beyond their past differences: Nicolas Sarkozy recently stated that: following colonialism, France entered into “a new period of economic prosperity and tried to forget that period and with it, all of the harm and sacrifices”. ”Atrocities were commited on both sides. These abuses have been and must be condemned, but France cannot repent for having conducted this war." When asked about Algeria´s 50 year anniversary of independence, Abdelaziz Bouteflika said: both countries must “look towards the future” and acknowledge this event “with a spirit of moderation, trying to avoid reference to the extremisms on either side”.

Yet, despite their willingness to simply turn the page, as former Algerian President Houari Boumedienne once said: history “cannot be torn up”. Algeria continues to demand a formal apology for French colonial rule and its treatment of Algerian Muslims. Until this takes place and France also addresses the widespread discrimination towards North African descendants in its own society, France´s colonial past will continue to haunt its present and its future.

This 50th anniversary is a unique opportunity for historians and the media to shed essential light on the political silence and hypocrisy that has and continues to plague the lives of generations. When all is said and done however, justice lies in the hands of its beholders.