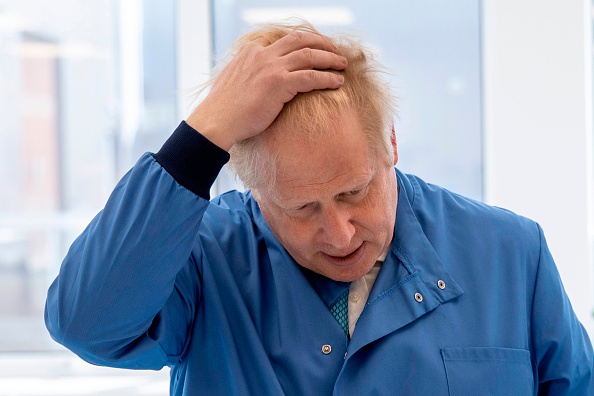

While the newly released data is disputed by scientists whose modelling of the likely shape of the UK epidemic is relied on by the government, Prime Minister Boris Johnson is facing mounting criticism over the government’s failure to put in place an adequate testing regime to manage the crisis. Johnson’s dramatic hospitalisation on Sunday night, followed by a move into an intensive care unit on Monday, has added to the air of crisis hanging over Britain’s attempt to control the virus while screening fewer people than other nations at a similar stage of the epidemic.

Responding the pressure, the UK said on Wednesday it aimed to roll-out millions of coronavirus tests in months. The move came after England’s Chief Medical Officer conceded on Tuesday that there were lessons to learn from Germany and Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab testing said there was “more work to do” on testing.

While Britain is struggling to carry out 15,000 tests a day — up from only 1,500 at the start of the crisis — Germany has been recording tests of some 50,000 a day. Testing was also used aggressively in countries like South Korea and Singapore to establish whether someone may be infectious to others and to screen essential workers who may have only mild coronavirus symptoms, or who are asymptomatic. Even America, which under Donald Trump has been slow to accept the impact of the disease, is now testing more people per capita than the UK. The need to test everyone with symptoms, track their contacts and isolate and test those people, in turn, was even a critical part of the strategy to eliminate the previous viruses such as Ebola, Sars, Mers.

There are several reasons the government has failed to increase the number of tests. The testing kits have to be purchased in a global marketplace where demand has now exceeded supply. But many also believe that the government’s initial controversial “herd immunity” strategy, which put mass testing as a secondary concern, cost them precious time.

In March, it was claimed that the British government was hoping to reduce the impact of the virus by allowing it to “pass through the entire population so that we acquire herd immunity”. The UK’s Chief Scientific Officer Sir Patrick Vallance said on March 12: “It’s not possible to stop everyone getting it and also it’s not desirable because you want some immunity in the population to protect ourselves in future.”

The official view was that mass infection was inevitable with projections of 40 million people contracting the disease. The UK, therefore, gave little attention to testing, isolation and quarantine – basic public health interventions – unlike other countries including South Korea and Germany.

But on March 16, the government abruptly changed tack when warned by scientists at Imperial College that its “mitigate” strategy could lead to 250,000 deaths and see the NHS overwhelmed. Anthony Costello, a UK paediatrician and former director of the WHO, also fiercely criticised the decision to stop tests. “For me and the WHO people I have spoken to, this is absolutely the wrong policy,” he said. “The basic public health approach is playing second fiddle to mathematical modelling.”

For now, the testing is crucial for controlling the spread of the virus. The World Health Organization director-general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has a simple message to countries on how to deal with the coronavirus outbreak in March: 'Test, test, test.' He urged countries to test more suspected cases, warning that they 'cannot fight a fire blindfolded'.

But the UK is currently competing with every other nation to obtain the kits it needs and its initial herd immunity strategy has pushed it the back of the queue. Other obstacles to adequate testing include Britain’s centralised state-funded health system, which is poor at rapidly boosting testing capacity. All coronavirus tests were initially processed at a single Public Health England laboratory, though several other public labs are now also handling the tests. British officials also blame shortages of swabs to take samples and of chemicals known as reagents, which are needed to perform the tests, for the delay in ramping up testing.

Moreover, the UK’s 100,000-a-day target has been thrown into doubt in recent days by the fact the government previously ordered millions of antibody tests from China and other countries millions to determine whether people have contracted the virus in the past and therefore may have immunity – which were proven to be ineffective and had to be thrown away. These tests are thought to be key in letting those who have already been through the virus return to work and begin to ease the country's lockdown.

Still, the government is confident that it will meet its target. Government testing adviser John Newton said the 100,000 daily test target was feasible, and that 20,000 National Health Service workers had now been tested. "Testing capacity now is not what we would like, but it is by no means inconsiderable in terms of what we need," Newton told a committee of members of parliament on Wednesday. "We do anticipate that the need will increase dramatically, and therefore we want to get as much testing in place as possible."

The government also said a business consortium had launched plans to develop millions of the DIY finger prick testing kits to distribute to homes across the country. The UK has asked UK businesses to join in a “national effort” to make the testing kits, similar to what was done for ventilators. But Newton said he did not expect such tests to be widely available by the end of April.