Every culture has a myriad of folktales that have been passed down from one generation to the next, mostly through oration. Nevertheless, as writing became a more widely used tool a number of said tales have been written down and collected in book form. In 19th century Germany, the Grimm Brothers compilated a number of European fairy tales such as Cinderella and Red Riding Hood into a single book which became a great hit. Meanwhile, the Arabs and Persians have the 1001 Nights tales, which are made up of stories like Aladdin and Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves. While these cultures identify with these numerous folktales, the Kurdish nation seems to identify with is Mem u Zin, which was written by Kurdish poet Ehmede Xani in the 17th century. The epic revolves around two star-crossed lovers Mem and Zin, who are prevented from embracing each other due to external factors coming in their way. What is significant about Mem u Zin is the fact that Xani chose to write the epic in his mother tongue Kurdish, rather than the other three widely used languages namely Arabic, Anatolian and Persian. Xani’s passion for the Kurdish language is also evident in his work on Nûbihara Biçûkan (The Spring of Children), a children’s Arabic to Kurdish dictionary. His decision to write in Kurdish was a risky one, due to the Ottoman Empire’s systemic efforts to oppress religious, ethnic and linguistic minorities.

In spite of the epic’s significance, the work has seldom been published up until the modern era, as no Middle Eastern government wanted the story to be published. For instance, one of the first modern publications came in 1898 in the Cairo based Kurdish magazine called “Kurdistan”, a publication that was subsequently shut down by Ottoman authorities.

The reason why many Kurds feel a deep connection to the epic is twofold, first it was one of the first significant pieces of literature to be written almost entirely in Kurdish (a few of the sentences are in Arabic and Persian) and secondly the subject matter is seen as an allegory for the Kurdish nation’s continuing quest for statehood. While several versions and translations of the tale have been published since the 1920s, for the purposes of this book review I will use the English translated version of Feryad Fazil Omar, the founder of the Institute of Kurdish Studies Berlin. In addition to his writing and work in the Institute, Omar also teaches at the Free University of Berlin.

MEM AND ZIN AS SYMBOLS OF STATE AND NATION

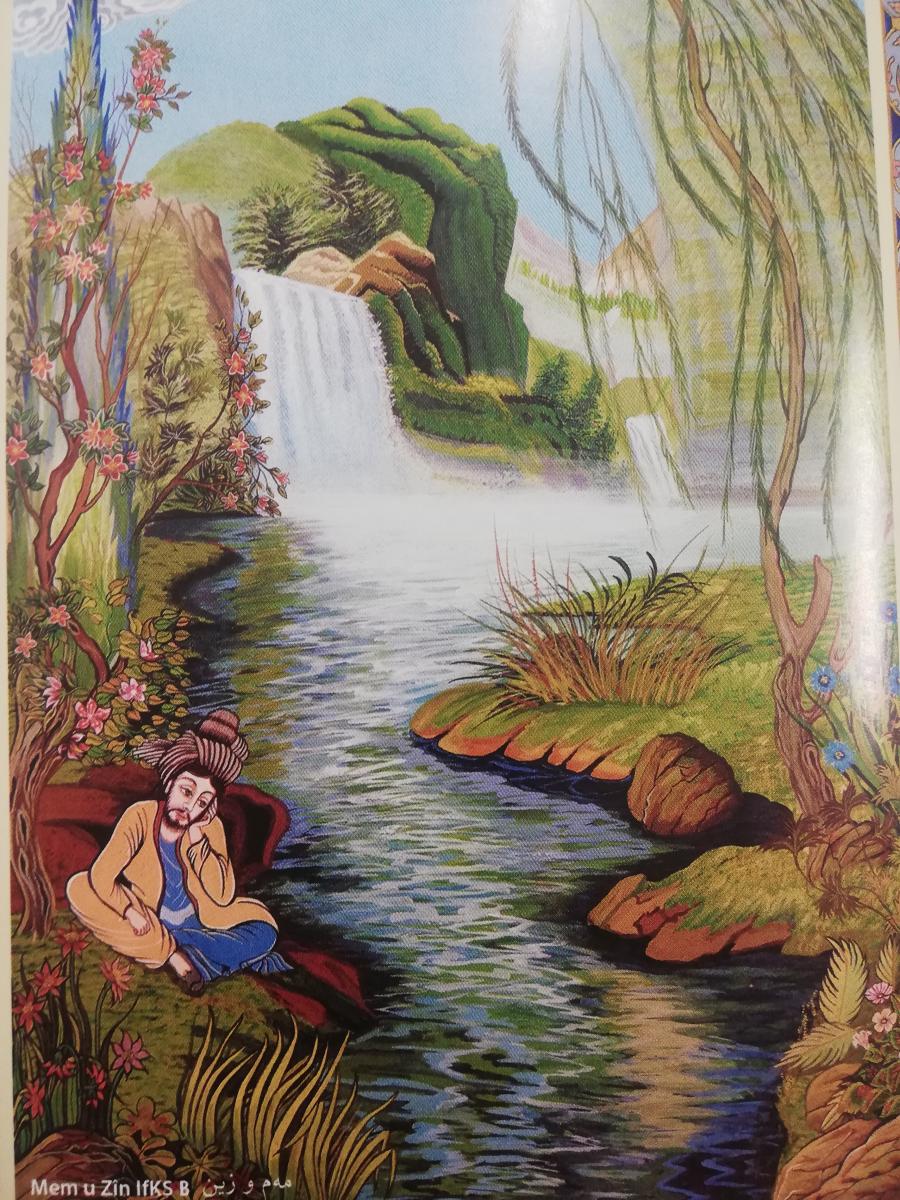

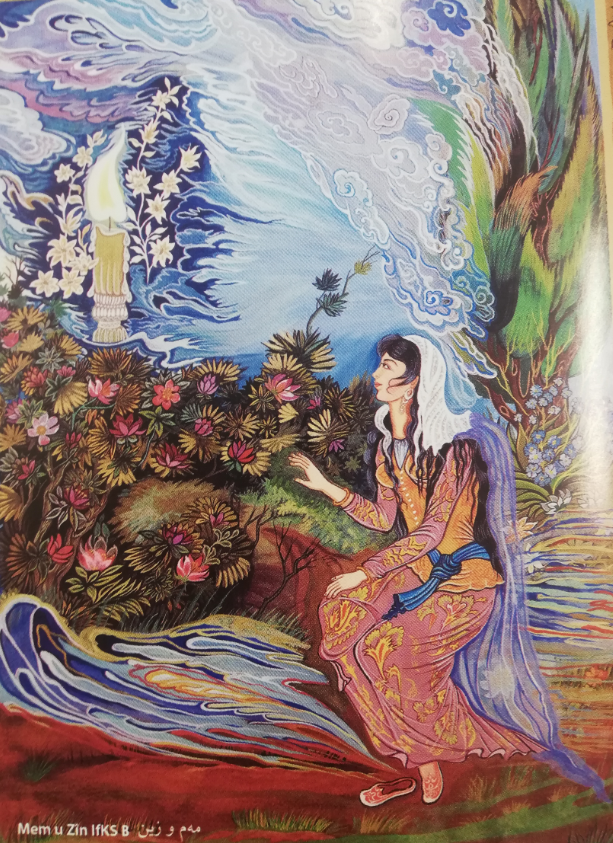

On the surface, it seems like the story of Mem and Zin is similar to that of Romeo and Juliet; two young lovers who cannot fulfill their wish of marriage due to circumstances beyond their control coming in their way. In the story, Mem is shown to be quite handsome and a talented poet and above all he is an honest man. Meanwhile, Zin, the Prince of Botan’s sister, is shown to have an impeccable, pure and angelic beauty. However, the fact that Mem was a clerk’s son meant that he wasn’t of noble or aristocratic birth; ergo the prince would probably not grant him his sister’s hand in marriage.

In spite of his lowly status, Mem was a trusted confidant of Prince Mir, but this trust was soon broken thanks to Bekir Margewar the prince’s deceitful advisor. In the story, Bekir is conniving, cunning and often devises schemes aiming to make people fall out with the Prince and is even compared to Satan throughout the book. Funnily enough, the Prince Mir is aware of Bekir’s trickery but he still keeps him by his side. The reason for this is because the Prince views Bekir’s Machiavellian planning, which he severely lacks, as a necessary evil to keep his principality in check. As soon as Bekir finds out about Mem and Zin’s love he devises a plan in which Mem is tricked into revealing the affair to the Prince. Bekir’s plan worked and as soon as Mem tells the prince, he is imprisoned. As such, the separation of Mem and Zin can be seen as the separation of the Kurdish nation from the desired Kurdish state. In this allegory, Zin can symbolize the Kurdish nation which is kept away from statehood, i.e. Mem. What completes this allegory further is the fact that a government authority figure, the Prince, is the one that is keeping them separate, just as state actors such as the Turkish, Iranian and Syrian governments have oppressively subjected the Kurds and kept them from getting a state of their own. Later in the epic, the imprisoned Mem seems to convey his own rejection of authority figures in general: “The rule of ministers and princes is a sham. For me, all they embody is a hoax, illusion” (pp. 263).

Mem’s friends also represent the Kurdish nation and its struggle. After he is imprisoned, Tacedin, Mem’s closest friend, gathers his compatriots to free Mem. Tacedin and his friends (the nation) value Mem and his freedom (the state), and they seem willing to fight a brutal battle to attain his freedom. As they rid their horses to the Prince, a passage reads: “The horses’ hooves were pounding loud upon the ground, as if to dig fresh graves for foes who’d soon be dying. On the next page, Tacedin is asking the Prince to free Mem, during which he says something notable to the sovereign: “Unless you change your mind (on Mem’s imprisonment), we’ve lost our public face. We’ll have to flee and emigrate to far Damascus. This alludes to the Kurdish diaspora’s migration patterns, as many of them flee to escape the wrath of oppressive state actors.

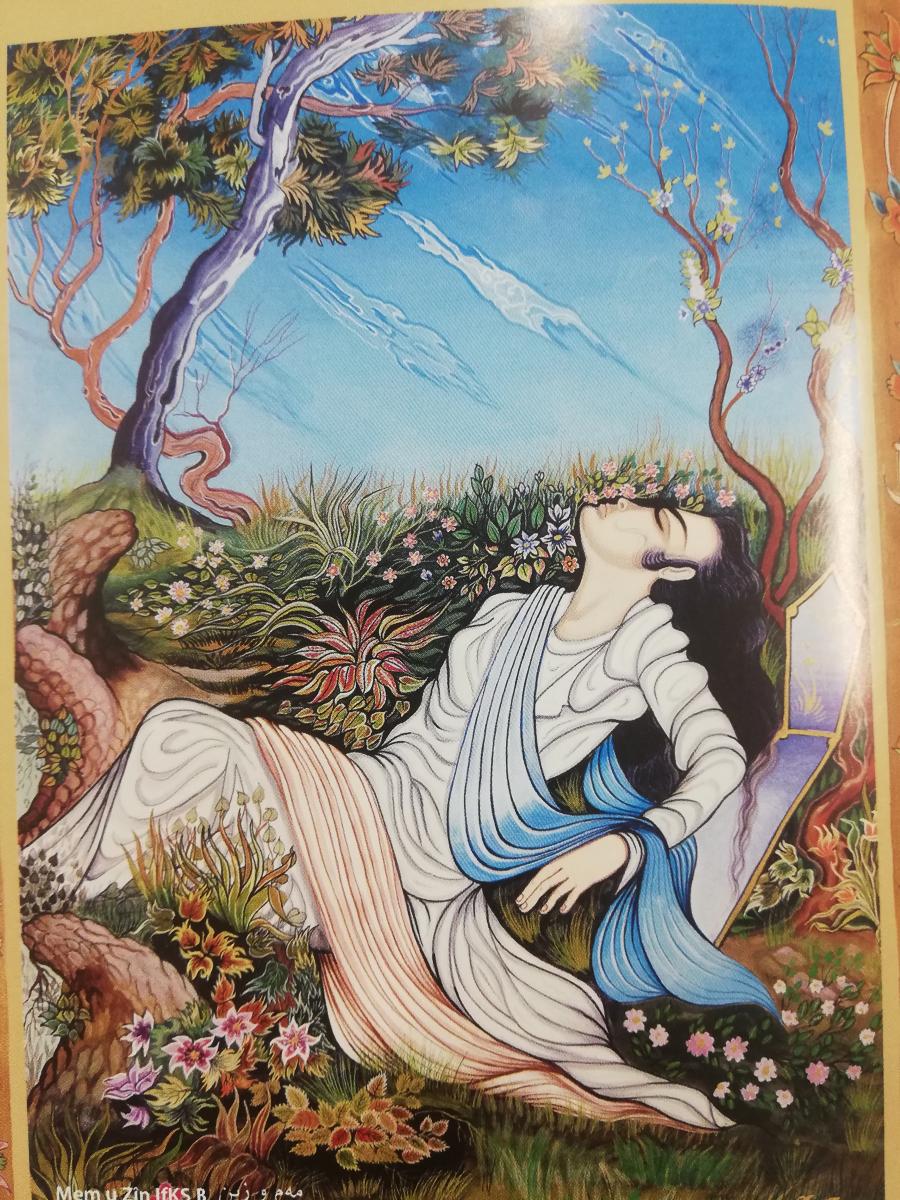

This tale is also one of hope, despite its tragic ending. If you haven’t read the epic yet, you might want to turn away now because of spoilers. Mem ends up dying in prison, something that brings great sadness to Zin as well as the people of Botan. Because of this, Zin loses her beauty, essence and will to live. It is noted that during funeral processions, Zin appeared to be extremely slender and seemed to have aged years. Just as Mem died due to being separated from his beloved, Zin was destined for the same fate. Nevertheless, the two do reunite in the physical world, as they share the same grave and the spiritual world as Zin’s soon meets with that of Mem’s. In a similar sense, though the Kurdish nation is physically separated from a state, the nation is still united in the hope that one day it will achieve the dream of statehood.