Despite decades of arms control and post–Cold War reductions, nuclear weapons remain a central feature of global power. As of early 2026, nine countries possess an estimated 12,300 nuclear warheads—a sharp decline from Cold War peaks but still an extraordinarily high and dangerous level.

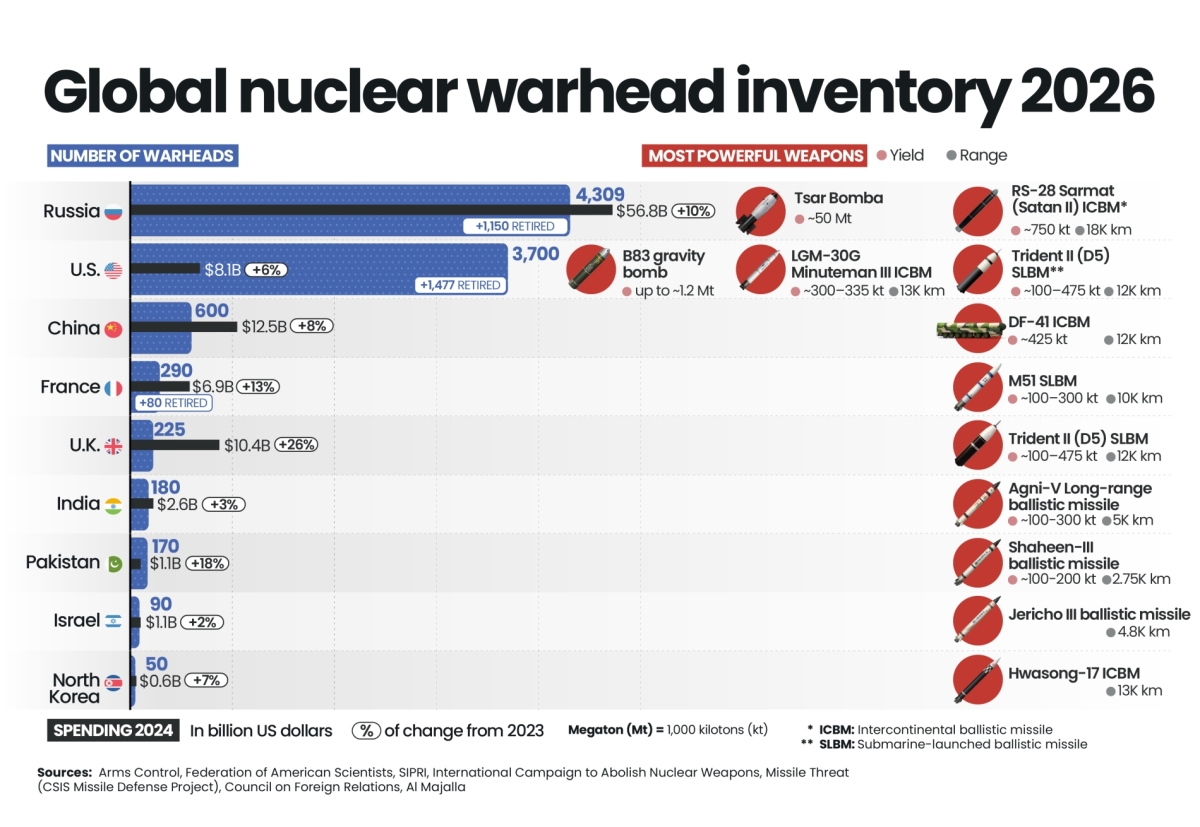

The global balance is overwhelmingly concentrated. The United States and Russia together control about 86% of all nuclear warheads and 83% of those available for military use. Roughly 9,600 warheads are in active military stockpiles, with nearly 3,900 deployed on missiles, aircraft, ships, and submarines. About 2,100 warheads remain on high alert, ready for launch within minutes. While overall inventories are shrinking, this decline is slowing and depends almost entirely on the dismantling of retired US and Russian warheads, not on new disarmament commitments.

At the same time, the number of operational warheads is rising. China, India, Pakistan, North Korea, the United Kingdom, and possibly Russia are expanding their arsenals, while France and Israel remain stable. This trend coincides with a surge in spending: global nuclear weapons expenditures surpassed $100bn in 2024, up 11% in a single year, underscoring a renewed reliance on nuclear deterrence.

This shift is occurring as the New START treaty—the last major agreement limiting US and Russian strategic nuclear forces—expires, removing transparency, verification, and numerical caps from the world’s two largest arsenals.

Against this backdrop, Iran’s nuclear programme has returned as a focal point of international tension. Iran, an NPT signatory, insists it does not seek nuclear weapons. Yet Iran has accumulated around 440 kilogrammes of uranium enriched to 60%, significantly shortening the technical path to a weapon.

The result is a more volatile nuclear landscape: fewer rules, higher spending, expanding arsenals, and rising regional flashpoints—challenging the spirit and credibility of global non-proliferation itself.