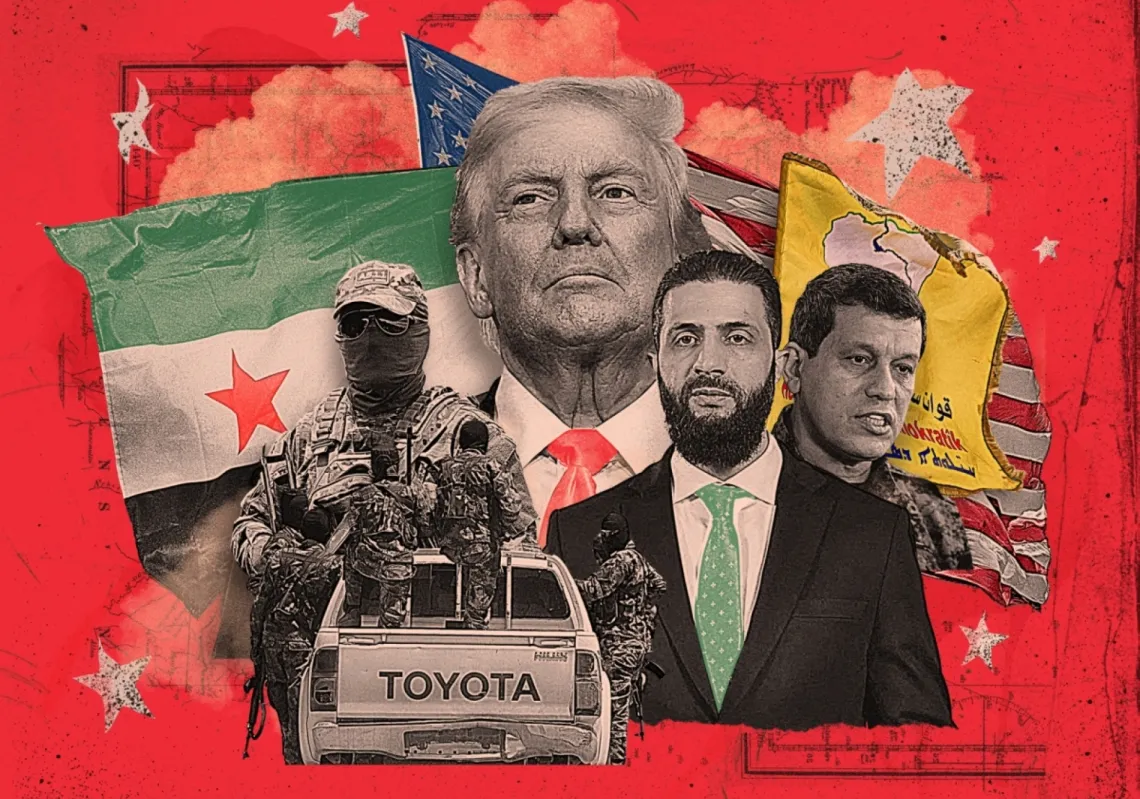

A terrorist bombing struck the St. Elias Church in the Dwelaa district of Damascus, marking the first attack of its kind since 1860. Syrian state media has pointed fingers at the Islamic State (IS), with the suicide operation claiming the lives of 22 Syrian citizens so far. This stands as the most significant challenge for President Ahmed al-Sharaa since he led the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad’s regime last December.

Syria has not conducted a population census since 2011, following the displacement of millions and the deaths of hundreds of thousands in battles and prisons—not to mention the missing, those unaccounted for in records, and children born in refugee camps who remain undocumented.

The Christian population, once 10% of Syria’s total before 2011, has dwindled to just 2%. This attack may accelerate its further decline in the coming months and years, despite the Syrian authorities’ efforts to protect them during the recent Easter celebrations, where no assaults were recorded in Damascus or other Syrian cities.

And while churches across the country did get swept up in the violence of the Syrian civil war and sustained damage, the St. Elias Church bombing in Damascus is the first time in over a century and a half that such an overt attack was carried out.

The infamous sectarian violence of 1860

The 22 June attack evokes memories of the infamous 1860 sectarian violence, when mobs stormed the Christian quarter of Damascus, burning and destroying it entirely. That incident was a repercussion of much broader sectarian violence that erupted earlier in 1860, between Maronite Christians and the Druze in Mount Lebanon.

The bloodshed in Damascus began on 7 July 1860, when Muslim youths entered the Bab Touma district, drew crosses on the ground, and trampled them underfoot. Their arrest and forced cleanup of the streets provoked outrage. One resident cried out, “O Muslims, O followers of Muhammad—Muslims are sweeping the Christians’ streets!” The crowd roared back in unison: “O zeal for faith!”

Meanwhile, thugs, mercenaries, and agitators flooded into Bab Touma, their numbers swelling to 20,000—just as Ottoman troops withdrew from the Christian quarter. They burned every church, attacked monks, and killed eight within the first hours. Within a week, 5,000 Christians had been killed. The violence spread to Protestant and Catholic missions, the Spanish monastery, the French Lazarist convent, the Asiyya School, and the Sisters of Mercy—a charity recently established in Damascus with funding from Napoleon III.

The Maronite Cathedral of St. Anthony in Bab Touma, the Armenian Catholic Church of the Queen of the World, the Greek Catholic Church of Our Lady of the Dormition, and the Syriac Catholic Church of St. Paul were all reduced to rubble. Even Damascus’ countryside was not spared: three Christian homes were destroyed in Wadi Barada, five Christians were killed in Bloudan, and 52 houses were torched.

The same horrors unfolded in Dummar, Maarat Saydnaya, and Maaruna, where 15 Christian youths were butchered. Only the Christians of Sarghaya survived, shielded by a Muslim nobleman. Remarkably, the Midan district—outside the city walls—remained untouched. Neither its Christians nor its churches were attacked.

Emir Abdelkader: The Saviour of Damascus

Algerian Emir Abdelkader el Djezairi, a resident of Damascus since the 1850s, opened the doors of his grand mansion in the Al-Amara quarter to shelter Christians fleeing the massacre.

Armed and supported by Muslim notables—including Saleh Agha Al-Mahayni, Saleh Al-Mawsili, and Sheikh Abdullah Al-Bitar—he confronted the mob at his doorstep, shouting: “Is this how you honour the Prophet Muhammad? Not a single Christian under my roof will be harmed—they are my brothers.” Among those who also helped protect Christians was the great-grandfather of Syria's first president, Mohammad Ali al-Abed, and the uncle of future economy minister, Mohammad al-Imadi.

Emir Abdelkader's bravery earned him global admiration. Gifts poured in: gold-plated pistols from Abraham Lincoln, a sword from Queen Victoria, a medallion from the Pope, and France’s Legion of Honour from Napoleon III. In 1915, a US city (Elkader, Iowa) was named after him, and UNESCO later honoured his legacy with a human rights chair in his name.

Reconstruction wave

After 1860, Damascus saw a wave of church reconstructions and the establishment of a few new foundations. The building campaign aimed to reassert the Christian identity of Damascus and compensate the community for its colossal loss. The Greek Orthodox Cathedral of St. John of Damascus re-emerged in late 1860, while the restored Al-Mariyamieh Cathedral, seat of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch and All the East, was rebuilt in 18679, incorporating the former chapels of Saints Cyprian and Justina. It had been completely destroyed in 1860.

The Syriac Catholic Church of St. Paul was rebuilt in 1863, followed by the Armenian Catholic Church (reopened as a Jesuit centre), and the Church of St. Sarkis (pre-Islamic in origin). Strangely enough, the French Mandate years saw very little church construction, despite attempts to exploit sectarian tensions during the 1925 Syrian Revolt.

During the Syrian uprising against the Mandate, the French asked Christians to draw large crosses on their rooftops to avoid being shelled by French warplanes and then ordered soldiers out of the neighbourhood, hoping that the Muslim mob would attack it again, a la 1860, but that never happened.

Post-independence, new churches emerged, albeit slowly. St. George’s Syriac Orthodox Church was inaugurated under President Hashim al-Atassi in 1951, followed by Our Lady of the Dormition in 1961, and St. Nicholas’ Church in Al-Mazzah in 1965. Under Hafez al-Assad, the Russian Orthodox Church was built in 1973, and Our Lady of Damascus (1975) was added. The most recent, St. Paul’s in Dummar, was built as an ecumenical sanctuary for all denominations.

Today, as Damascus mourns another attack on its Christian community, the ghosts of 1860 loom large—a reminder of both past horrors and enduring resilience.