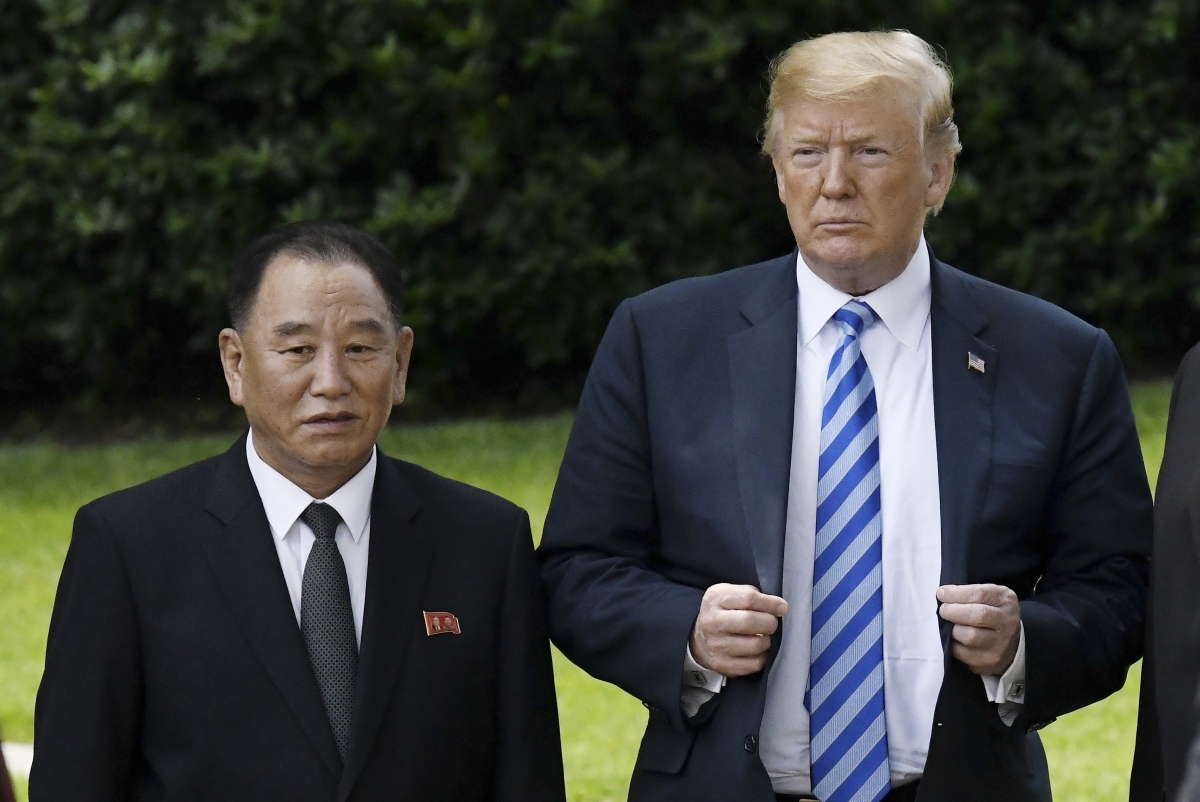

U.S. President Donald Trump, right, stands with Kim Yong Chol, vice chairman of North Korea's ruling Worker's Party Central Committee, stand on the South Lawn of the White House after a meeting in Washington, D.C., U.S., on Friday, June 1, 2018. (Getty)[/caption]

U.S. President Donald Trump, right, stands with Kim Yong Chol, vice chairman of North Korea's ruling Worker's Party Central Committee, stand on the South Lawn of the White House after a meeting in Washington, D.C., U.S., on Friday, June 1, 2018. (Getty)[/caption]

by Joseph Yun

Over the past few weeks, the on again-off again U.S.–North Korean summit has drawn a considerable amount of attention to the question of whether the meeting between U.S. President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un will even take place. But the danger of focusing on Trump and Kim’s game of hot and cold is that it is diverting focus from the more fundamental issue at hand: what a minimally successful agreement between Washington and Pyongyang should look like.

Achieving a substantive and mutually satisfactory agreement is a particularly complex challenge, as the two sides are starting from widely disparate positions that at the most obvious level seek sharply different outcomes. As Trump has made clear, success is defined as immediate CVID (complete, verifiable, and irreversible denuclearization), a difficult-to-grasp phrase that would elicit eye rolls from my North Korean counterparts whenever it was mentioned during our encounters. As for Kim, he is focused on the survival of his regime, beginning with the recognition of his country as a legitimate state, followed by an easing of economic sanctions. This mismatch between U.S. and North Korean goals has remained more or less consistent over the decades and has so far stymied all agreements that have emerged between the two sides since the first round of bilateral denuclearization negotiations in the early 1990s.

The stakes have grown far higher since last September, however, when the North Koreans successfully tested a thermonuclear device that yielded a blast approximately 15 times stronger than the bomb that struck Hiroshima in 1945. Two months later, Pyongyang launched its Hwasong-15 ICBM, which is capable of reaching virtually any place in the United States. At the same time, Trump’s “maximum pressure” campaign has begun to squeeze the North Korean economy more effectively than past sanctions and his warnings of a U.S. military response “like the world has never known” have rattled both China and South Korea to urge Kim to decelerate.

As a result, the parties’ divergent goals are now matched by equally differing perceptions of their relative negotiating power. Trump feels that he is the one holding the cards—that Kim has been so punished by the effects of the maximum pressure that he is ready to bargain away his nuclear weapons. Although South Korean President Moon Jae-in is adamant that Kim is serious about denuclearization, it is clear that, as the leader of a demonstrated nuclear weapons possessing state, Kim also believes he will enter the talks from a position of strength. In Kim’s mind, why else would the U.S. president agree to meet him one on one, a goal that both Kim’s father and grandfather were never able to achieve?

[caption id="attachment_55256473" align="aligncenter" width="4500"]

U.S. President Donald Trump, center right, shakes hands with Kim Yong Chol, vice chairman of North Korea's ruling Worker's Party Central Committee, next to Mike Pompeo, center, on the South Lawn of the White House after a meeting in Washington, D.C., U.S., on Friday, June 1, 2018. (Getty)[/caption]

U.S. President Donald Trump, center right, shakes hands with Kim Yong Chol, vice chairman of North Korea's ruling Worker's Party Central Committee, next to Mike Pompeo, center, on the South Lawn of the White House after a meeting in Washington, D.C., U.S., on Friday, June 1, 2018. (Getty)[/caption]

Given this gap, what can be realistically expected from the summit?

Whatever Trump promises, North Korea will not agree to what National Security Adviser John Bolton has in mind: an immediate surrender of all its nuclear arsenal and equipment, in which it will simply pack them up and ship them to Oak Ridge. Even Trump recognized that this was an unrealistic demand, opening the door to phased denuclearization when he told the press in his meeting with Moon on May 22 that while he would prefer an “all-in-one” deal, he recognized that North Korea “may not be able to do exactly that.” At the same time, Kim knows he needs to give up something to get the economic relief he clearly wants.

On the denuclearization side, there are easy, immediate deliverables, including memorializing North Korea’s current self-imposed moratoriums on nuclear and ballistic missile testing and opening the Yongbyon nuclear facilities for inspection and monitoring by the International Atomic Energy Agency. A much more difficult but nevertheless vital initial step is to provide a “true” declaration and accounting of all North Korean nuclear sites and fissile material. Pyongyang has adamantly resisted giving such an accounting in the past, a key reason for the collapse of the 1994 Agreed Framework and the six-party talks. But such a declaration, accompanied by an agreement on full verification, will test the seriousness of both Kim’s claim that he is seeking a different type of relationship with the United States and Moon’s claim that Washington should believe Pyongyang this time.

Beyond the immediate steps, the negotiation must produce a clear timeline for the ultimate goal: the disablement and dismantlement of all North Korean nuclear and ICBM facilities, material, and devices. If Kim agrees to a swift timeline—say by 2020—the cadres of skeptics in Washington, Seoul, and Tokyo will be silenced. (Although they will continue to assert, rightly, that implementation is everything.) More realistically, the United States must at the very least initiate a serious process to get there.

On the other side of the ledger is what Kim gets in return. The most obvious and immediate win is his meeting with the U.S. president, a sign of recognition that the North Koreans have sought for decades. In my meetings with North Korea’s foreign ministry, its officials have repeatedly emphasized that only a leader-to-leader dialogue could break the nuclear impasse. At the root of this desire lies their central concern: regime survival. To reach a clear outcome on denuclearization, there has to be a corresponding clarity on security guarantees. Diplomatically, both North Korea and the United States should show their serious commitment to normalizing relations by agreeing to an end-of-war statement and the opening of liaison offices in Washington and Pyongyang. A declaration from the United States that it does not have “hostile intent” and will begin normalization and peace treaty negotiations is equally needed as a security guarantee.

On the economic side, an immediate deliverable would be humanitarian assistance, if not from the United States then through South Korea and the international community. The larger agreement for sanctions relief should correspond to verified progress on denuclearization. On the military side, the Pentagon should agree to review and, as appropriate, adjust future plans for the upcoming August U.S.–South Korean joint exercises and, especially, any drill involving strategic assets (those capable of delivering nuclear devices). Above all, the summit should establish a diplomatic process to negotiate a peace treaty that formally ends the Korean War.

This, of course, is a tall order that will likely take years to complete. Therefore, in the brief remaining time before the summit, U.S. diplomats, led by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, should concentrate on both a broad vision for the future of U.S.–North Korean relations and on the immediate steps needed to finally reach an agreement that will get Washington the denuclearization that it wants and Pyongyang the security guarantees that it seeks. Only then can the two sides bridge the gap between what they hope to achieve and what is realistically possible.

This article was originally published on ForeignAffairs.com.