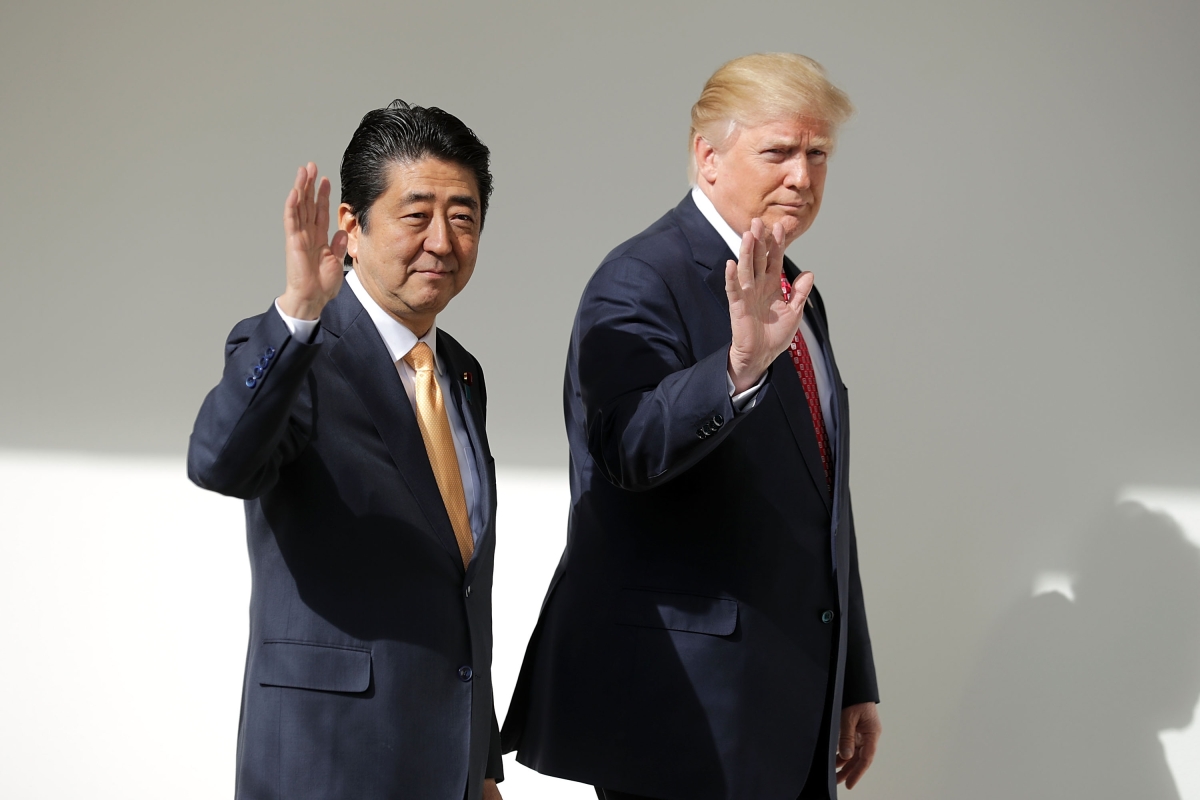

U.S. President Donald Trump and Japan Prime Minister Shinzo Abe walk together to their joint press conference in the East Room at the White House on February 10, 2017 in Washington, DC. (Getty Images)[/caption]

U.S. President Donald Trump and Japan Prime Minister Shinzo Abe walk together to their joint press conference in the East Room at the White House on February 10, 2017 in Washington, DC. (Getty Images)[/caption]

by Sheila A. Smith

When news broke on March 8 that U.S. President Donald Trump had agreed to meet with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had plenty of reason to worry. Japan, of course, would be delighted if the Trump-Kim meeting were to put Pyongyang on the path to verifiable and irreversible denuclearization, but Japanese leaders have long been and will continue to be concerned about the arsenal of North Korean missiles that could reach them. From Tokyo’s perspective, the problem on the Korean Peninsula is not simply that Pyongyang’s nuclear and missile capabilities are growing; it is also that Kim blatantly desires to demonstrate those capabilities, and to do so at the expense of Japanese security. North Korea has a reputation of not abiding by agreements, and today it has a lethal military arsenal to show for it. Thus, even if Trump and Kim hash out a deal, there is little reason for Abe to believe that Kim will give up his nuclear and missile capabilities, given how hard he has worked to develop them up to now. Expect Japan to be very skeptical, and to demand sustained evidence of Kim’s intentions. Like U.S. and South Korean experts, Tokyo policymakers have little reason to trust Kim’s quick about-face.

TARGET JAPAN

Japan has felt the brunt of Kim’s intensified missile testing for over a year. Of North Korea’s 11 successful missile launches in 2017, five fell within 200 nautical miles of the Japanese islands. In late August, Kim sent the first of two intermediate-range ballistic missiles he claimed could eventually reach the United States. In September, he went further and conducted a nuclear test, again seeking to prove that North Korea was just about to reach its goal of a deliverable nuclear weapon—a threat severe enough that it could decouple Seoul and Tokyo from the United States.

Japan has long worried about North Korea’s missile program. In 1998, the first launch of a North Korean intermediate-range missile over Japanese territory alerted Japan’s security community to its own vulnerability. Tokyo has struggled to keep pace with North Korea’s proliferating missiles. New satellites were built to ensure early warning capability, and in 2002, Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi visited Pyongyang to meet with Kim’s father, Kim Jong Il, in an effort to ease tensions. The two leaders issued the Japan–North Korea Pyongyang Declaration, which included a promise that North Korea would place a moratorium on missile testing—a promise that Pyongyang broke shortly thereafter, launching a volley of missiles in July 2006.

From Tokyo’s perspective, the problem on the Korean Peninsula is not simply that Pyongyang’s nuclear and missile capabilities are growing; it is also that Kim blatantly desires to demonstrate those capabilities at the expense of Japanese security.

North Korea’s current leader has only escalated the situation since assuming power. During Kim Jong Il’s entire 17-year rule, North Korea conducted 46 missile tests; since Kim Jong Un came to power in 2012, it has conducted 99. Today, Pyongyang has a larger arsenal of missiles capable of reaching Japan than it did a decade ago. Not only that, these missiles are deployed on mobile launchers, making an imminent missile attack more difficult to detect.

In response to this new threat, Japan has begun to invest more in ballistic missile defenses. The budget for FY 2017 allocated 67.9 billion yen (about $600 million) to missile defense, including high altitude ship-based systems for its AEGIS destroyers and land-based PAC-III missile interceptors. From 2016 until today, these have been on high alert. Last year, Abe ordered a new effort to mobilize civilian defenses as well. When, on August 29, a North Korean missile flew over Hokkaido, Japan’s J-alert system warned citizens there to take cover. Since then, businesses, schools, and municipalities nationwide have begun to consider how to seek shelter in case of a North Korean attack. In Japan’s new five-year defense plan to be announced later this year, additional funding on a land-based system to bolster a response to ballistic missiles is expected.

PYONGYANG AND WASHINGTON-TOKYO TIES

North Korea has offered its share of setbacks to the U.S.-Japanese relationship. Ever since December 2002, when Kim Jong Il announced that North Korea would no longer tolerate inspections of its nuclear facilities by the International Atomic Energy Association (IAEA), the United States and Japan have gone in and out of sync on their approaches to Pyongyang. Japan partnered with the United States and South Korea in their first attempt to negotiate a change of heart in Pyongyang in the early 1990s. Under the Agreed Framework of 1994, Tokyo provided funding for the light-water reactors that the Korean Energy Development Organization (KEDO) was to give North Korea in order to fuel the latter’s energy needs. At the time, Tokyo and Seoul shared an understanding of the problem and a commitment to negotiating a path away from the Kim regime’s nuclear breakout.

Yet North Korean backtracking undermined not only this arrangement but also, ultimately, the diplomatic unity of Seoul, Tokyo, and Washington. A new president in Seoul, Kim Dae-jung, wanted to pursue an aggressive engagement strategy, but this, too, floundered. Then the U.S. administration of George W. Bush came into office, identifying North Korea in 2002 as part of an “axis of evil” and, in 2005, sanctioning a Macau bank that kept the finances of the Kim regime. Stung by the failure of its own role in the KEDO program, and with growing confirmation that the North Korean regime had systematically abducted Japanese citizens in the 1970s, the Japanese public lost interest in funding any negotiated compromise with Pyongyang. Japan shifted away from supporting negotiations with the North to a far harder and more skeptical view of the Kim regime’s intentions. Japan’s willingness to provide economic assistance as part of a regional settlement was evaporating, and even as the six-party talks—a further attempt at diplomacy involving China, Japan, both Koreas, Russia, and the United States—were launched in 2003, Japanese negotiators remained highly skeptical of North Korean intentions. For the first time, Tokyo also felt distanced by Washington as the United States sought to test the opportunity for a bilateral accommodation with the North Koreans.

Even if Trump and Kim hash out a deal, there is little reason for Abe to believe that Kim will give up his nuclear and missile capabilities.

Abe has thus witnessed how easily negotiations with North Korea can strain alliance ties. In fact, he has considerable experience in the ups and downs of international efforts to negotiate with the Kim family. He served as chief cabinet secretary to Koizumi during his negotiations with Pyongyang and became an outspoken hard-liner on Japan’s compromise with North Korea when Kim Jong Il failed to account for additional abductees. Speaking forcefully about Japan’s need to resolve the abductee issue, Abe went on to become one of his country’s most vocal critics of negotiations with Pyongyang.

Since returning to the prime minister’s office, however, Abe has briefly tested the waters of negotiation. When Kim Jong Un offered to restart talks on the fate of Japanese still living in North Korea, Abe approved a Japanese government response, and a negotiating team—which included officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as well as the National Police Agency—visited Pyongyang in October 2014. Nothing came of the effort, however, as North Korea once more failed to produce any reliable new information on the fate of Japanese still living within its borders.

[caption id="attachment_55256001" align="alignnone" width="940"]

A pedestrian looks at a television screen displaying a map of Japan (R) and the Korean Peninsula in Tokyo on August 29, 2017, following a North Korean missile test that passed over Japan. (Getty Images)[/caption]

A pedestrian looks at a television screen displaying a map of Japan (R) and the Korean Peninsula in Tokyo on August 29, 2017, following a North Korean missile test that passed over Japan. (Getty Images)[/caption]

THE TRUMP-KIM MEETING THROUGH ABE'S EYES

Ever since February 2017, when North Korea launched a missile into the Sea of Japan during Abe’s visit to Mar-a-Lago, the prime minister has counted on close consultations with Trump to ensure that Japan’s security concerns are appreciated and represented in the international community’s response to the threat. And under Abe, the Japanese government has been more than willing to demonstrate how seriously it takes this growing missile threat. Over the past year, U.S.–Japanese–South Korean trilateral military coordination has expanded the role of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces. And in discussions for the next Japanese five-year defense plan, due to be announced by the end of 2018, there have been calls to strengthen the country’s ballistic missile defenses even more. Washington and Tokyo are also discussing what kind of conventional strike options might help deter Pyongyang from miscalculating about Japan’s determination to defend itself.

For all of this enhanced cooperation, however, Japan anxiously watched as Trump tweeted threats of retaliatory “fire and fury” last August, and it became especially wary of the idea that the Trump administration was considering a preventive strike on North Korea. While in Tokyo in November, Trump wondered aloud why Japan didn’t just shoot North Korean missiles down, revealing a lack of understanding of Japan’s defensive military posture. In early 2017, the Japanese government reminded the new U.S. administration of a memorandum of understanding accompanying the countries’ bilateral security treaty, which commits the U.S. government to consult with Tokyo should it want to use U.S. forces on Japanese soil for combat in third-party countries.

Now the risk to Abe is a different one. A diplomatic opening spearheaded by South Korean President Moon Jae-in during the Pyeongchang Olympics led to Trump’s acceptance of a meeting with Kim. Abe was persuaded to participate in Moon’s Olympic diplomacy and joined both the South Korean president and U.S. Vice President Mike Pence on the VIP platform with the North Korean delegation at the opening ceremony. In private meetings with Kim’s emissary, Abe reiterated his desire for denuclearization, holding fast to the principle that it is Pyongyang, not U.S. allies, that must bend.

Shinzo Abe has counted on close consultations with Trump to ensure that Japan’s security concerns are represented in the international community’s response to the North Korean threat.

When South Korean National Security Adviser Chung Eui-yong stood in front of the White House to announce the historic Trump-Kim meeting, Abe called Trump that very day. Japan’s prime minister plans to visit Washington in early April, prior to Moon’s summit with Kim that month and well in advance of any meeting between Trump and Kim, now tentatively scheduled for May. During his meeting, Abe will likely urge Trump to insist on denuclearization and to be unwavering in his commitment to the defense of America’s allies. Japan’s leader, like his predecessors, must be worried that the Trump administration will repeat the mistakes of the past and compromise too easily in an effort to avoid a military clash.

But Abe will also need to consider his country’s approach should the Trump-Kim meeting lead to serious negotiation. Like other members in the old six-party talks, Japan will want denuclearization to be complete, verifiable, and irreversible, the conditions set forth in the last round of talks with Pyongyang. Although the United States may be focused on denuclearization, Japan will need to reduce the North Korean missile threat. We should thus expect Tokyo to condition its support for a deal on a missile moratorium and some sort of disarmament framework that would reduce Pyongyang’s existing missile arsenal. Abe will also be hard pressed not to raise the fate of Japan’s abductees, which could complicate conversations with Washington and Seoul over diplomatic priorities.

This is not a propitious time for the Abe cabinet. Political scandal is building in Tokyo, one that links the prime minister to a questionable government land sale. On Monday, the Ministry of Finance admitted to altering documents before submitting them to Diet review, raising suspicion that they erased evidence of impropriety. A bureaucrat of the Ministry of Finance who was involved in the sale has committed suicide, and Abe’s finance minister and deputy prime minister, Taro Aso, is facing calls to resign. Abe’s fate in his party’s leadership election in September now seems to be in question.

Abe will need to safeguard his position as Trump’s closest confidante in Asia. In Japan’s lower house election last fall, Abe campaigned on his ability to keep Japan safe against North Korean belligerence. The Japanese public continues to believe its prime minister can fulfill that promise, largely because he has such a close relationship with the unpredictable U.S. president. Trump’s unexpected acceptance of a diplomatic opening to Pyongyang creates a far more difficult future for Abe—one that not only tests his ability to reduce North Korea’s threat to Japan but also tests his legacy as Japan’s most reliable defender.

This article was originally published on ForeignAffairs.com.