[/caption]

[/caption]

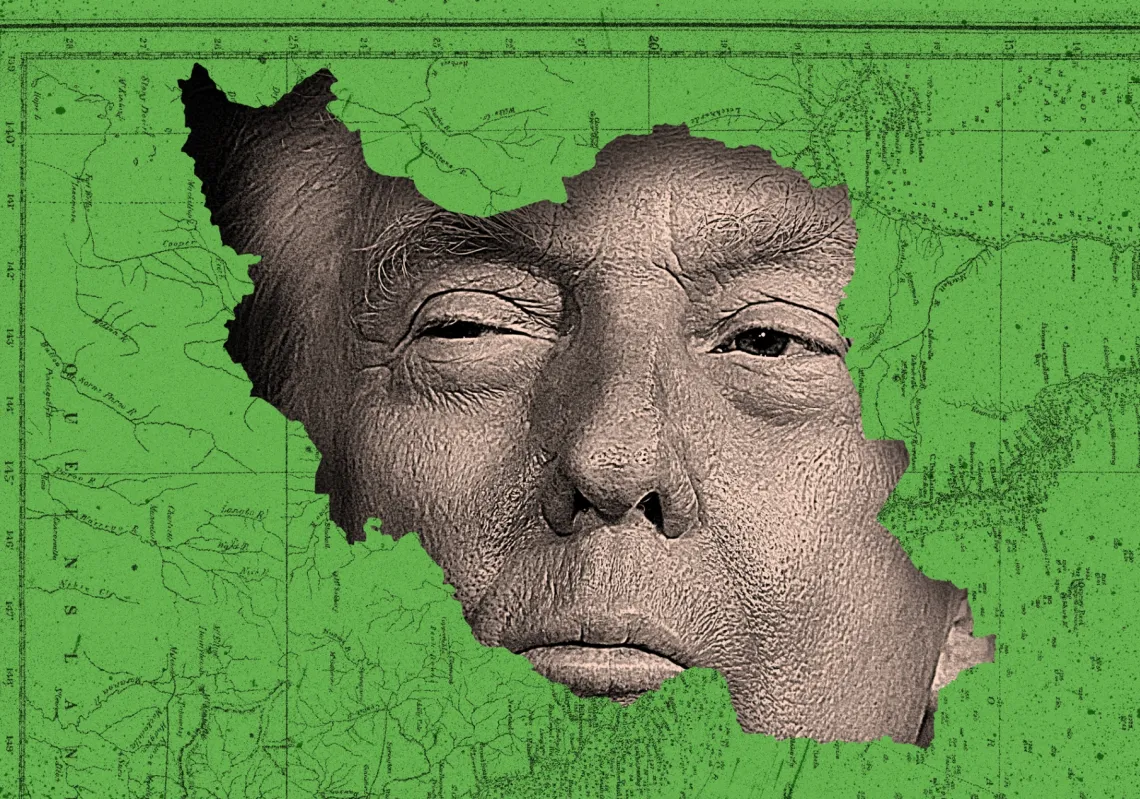

Over the past couple of weeks, speculations about an American or Israeli attack on Iran's nuclear facilities have dominated news headlines around the globe. With the IAEA's latest report on Iran's alleged nuclear weapon activities finally out, such talks have continued to surface even though the prospect of a pre-emptive strike in the near future remains slim.

To begin with, it is fair to say that IAEA's "much-awaited report", similar to the previous ones, has failed to reveal anything novel with regard to Iran's nuclear ambitions. That Iran is keen to acquire the know-how capability of assembling a bomb, as the report indicates, is nothing new and was in fact predicted by the Israeli Intelligence agency back in 1995. In addition, the current speaker of the Iranian parliament, Ali Larijani, had also, perhaps unintentionally, made this objective crystal clear during an official visit to Tokyo in February 2010 when he stated that Tehran wants to develop nuclear capabilities "similar to those of Japan". Japan does not have nuclear bombs of its own, but the lead time for the Japanese armed forces to assemble a bomb is 24 hours, and thus Larijani's remarks did indeed shed lights on the nature and scope of Iran's nuclear posture.

As such, and regardless of the Iranian government's intentions and the logic behind Iran's nuclear drive, today's talks of an attack are more likely to be part of a wider psychological campaign against the regime in Tehran with its advocates hoping that such rhetoric will help them to score political points against Iran in future negotiations. There are two broad reasons behind such assertion.

The firs t one, according to an analyst in Tehran, is that Iran is much more likely to react forcefully to a strike rather than, as it is commonly anticipated, seeking accommodation out of a fear of inviting massive reprisals by the US and its allies. To this end, Iran's aim would be to escalate the war into a regional conflict by projecting power to its neighbours and Israel. Not only the vast majority of Gulf cities with their skyscrapers are within the reach of the Iranian missiles, but Iran can also mobilise its sleeping cells in Dubai, Manama, and Kuwait City to steer social unrest and cause fear amongst the public there. This is not to mention the consequences of a possibly fuming reaction to a strike which has the blessing of the GCC governments by the vast Iranian community in the Gulf. Tehran could also target Americans and Europeans in Iraq and Afghanistan, and it will not hesitate to give the go ahead to Hizbullah and the Islamic Jihad to unleash their missiles towards Israel. And to make matter worse, all these will almost certainly increase the price of oil at a time of global economic crisis without Iran even trying to block the Strait of Hormuz.

Secondly, a cost and benefit analysis of the "Iranian threat" narrative in the United States and Israel foreign policy discourses helps to open the Pandora's box. Thanks to the Iranian threat and Iran's hegemonistic ambitions in the region, perceived or real, Washington has been able to establish a profitable market for its defence companies in the Gulf thereby increasing its influence over the Gulf States strategic decision making, while simultaneously expanding and justifying its massive military presence in the region. As for Israel, Iran's nuclear programme has enabled Tel Aviv to form a united Arab front or a buffer zone against its most powerful regional foe by manipulating Arab regimes fear of Iran and developing a common strategic interest in containing Tehran without making a single compromise over an issue that is of paramount importance to both elites and the public in the Arab world; that is, the Palestinian statehood. Surely, a nuclear Iran will change the regional balance of power to the detriment of US and Israeli interests, and thus there ought to be no doubts that they will seek to avert this by all means. For the time being though, maintaining the status-quo seems to be a better strategic option especially that last year Stuxnet attack has, according to various estimates, delayed Iran's progress towards "full-circle enrichment" for three years.

Looking into the immediate future, therefore, it can be expected that there will be tougher sanctions imposed on Iran by the US and its European allies. Regime change is now being seriously considered and given Iran's state of economy as well as the regime's unprecedented unpopularity, hard-hitting sanctions, not military strike, provide the most prudent option for an eventual termination of Iran's military nuclear programme which can only be arrived at once there is a new regime in charge. According to an Iranian activist, the unpopularity of the regime is evident in the public's indifference to the house-arrest of the so called Green Movement leaders: "they ultimately support the regime and the institution of the Supreme Leader, but people no longer do. So it does not really make any difference if they are free or not, we now want real change". A military strike, on the other hand, could have the negative effect of uniting the public behind the regime in a similar fashion to the Iran-Iraq war by encouraging the public to perceive the West and Iran's neighbours as enemies of the Iranian nation rather than the Iranian regime. In this case, not only Iran's maturing democratic movement will fade away, but the entire Iranian nation might then support the regime in its nuclear drive.