For Gulf Arabs, the entry of their centuries-old Persian rival into the elite club of nuclear-armed states would be a strategic development of ruinous proportions. It would exacerbate Sunni-Shiite tensions, challenge notions of Sunni superiority, fuel fears of more Iranian “meddling” in Arab affairs, and seal the Persian state as the region’s dominant power.

As Gerd Nonneman, Al Qasimi Professor of Arab Gulf Studies at Exeter University and Gulf expert at Chatham House, put it: “Their main concern is not direct military attack, but simply the sense that Iran, the big boy, will start to become more of a bully than it sometimes tries to be - It’s a more generic fear of Iran throwing its weight around.”

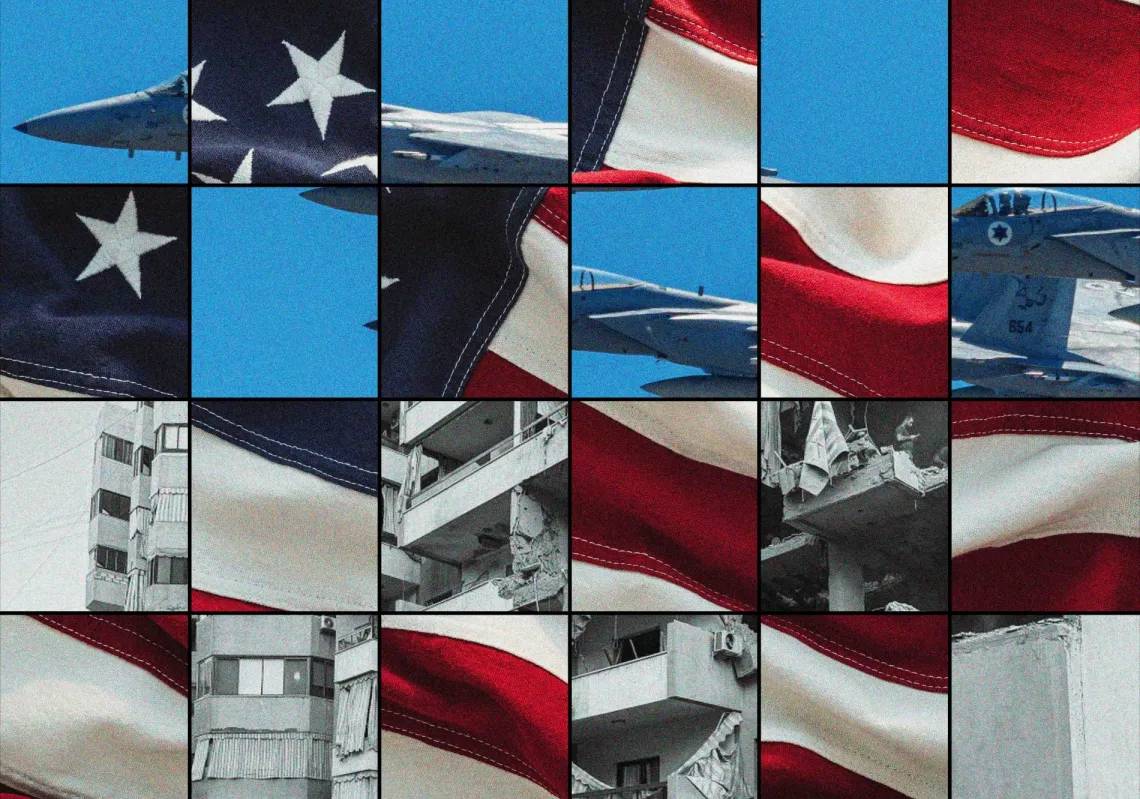

Iran’s recent willingness to talk about its nuclear program with U.S. and European officials has not lessened Gulf Arabs’ anxiety, mainly because they do not believe Iran will ever give up its nuclear ambitions. Although a U.S. or Israeli military strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities is emotionally appealing, most policy-makers oppose this option because of the deadly blowback Gulf states believe they would suffer from Iranian retaliation.

Beyond that, they have not come up with a unified response to their difficult neighbour, reflecting their long-standing inability to cooperate on major policies. The reality is that they have few good options and limited leverage to influence Iran.

More alarmingly, however, the first outlines of a nuclear arms race in the Gulf are emerging as Gulf states set up, or ponder setting up, civilian nuclear programs. To varying degrees, the Gulf states all seek to keep bilateral relations with Iran on an even keel in the hope that through engagement they can mitigate Tehran’s more bellicose tendencies. The friendliest are Oman, which has long history of good relations with Tehran, and Qatar, which wants to stay on Iran’s good side because they share a huge natural gas field.

The most skittish are Kuwait and Bahrain, which is particularly sensitive to the potential for Iranian subversion among its Shiite majority. Off-hand comments from Iranian officials that Bahrain is really Iranian territory only adds to its jitters.

The United Arab Emirates has perhaps the most complicated relationship to Iran. The two countries have a bitter, decades-long dispute over three tiny islands claimed by both -- and now occupied by Iran. At the same time, UAE’s Dubai is a major trading hub and investment depot for Iran, which benefits both sides.

Of course, it is Saudi Arabia’s response to Iran’s nuclear designs that matters most.

Riyadh maintains correct if not cordial relations with Tehran. Aiming to deprive Iran of rhetorical ammunition against it, Saudi Arabia has avoided commenting on Iran’s recent domestic troubles, including June’s post-election street protests and leadership divisions, as well as the recent suicide bombing that left six Revolutionary Guards dead in southeast Iran.

Some Saudi officials privately say they believe that these political woes, plus Iran’s troubled economy, will cause the country to implode before it can fully realize its nuclear ambitions. The Saudis, however, are not waiting around for this to happen. Like its Gulf neighbours, Saudi Arabia is concluding major arms purchases to keep its conventional forces updated.

The kingdom also signed a memorandum of understanding on nuclear cooperation with Washington last year and will sign another one with France during President Nicolas Sarkozy’s visit here in November. If the Saudis move forward and indeed launch a civilian nuclear program, they will be following the UAE, the first Gulf state to do so. Earlier this year, the UAE signed agreements with the United States that allow it to buy U.S. nuclear power technology and fuel.

Both states say these civilian programs are to meet future domestic energy needs. Foreign observers see a second motive as well. The Iranian nuclear threat is the reason why the GCC [states] are moving - toward acquiring nuclear technology,” wrote Kristian Ulrichsen, Kuwait Research Fellow at the London School of Economics. These moves are “a statement of intent to possess the option of going for a nuclear weapon at some point in the future, however unrealistic this may be...Certainly I don't think the reason is for power generation.”

The Gulf states “will follow the American lead up to the point where Iran is going to get a nuclear weapon and then they will have to make hard decisions,” says Greg Gause, a Gulf expert at the University of Vermont.

Lacking the indigenous technical infrastructure and scientific knowledge to start a crash weapons program, some observers suggest that some GCC Countries might buy a rudimentary bomb from a friendly state like Pakistan. It’s a frightening scenario, but Iran’s perceived determination to become a nuclear power is making for a scary future in the Gulf.

Caryle Murphy - Pulitzer Prize Winner in Journalism in 1991, is an independent journalist based in Riyadh. She is the author of “Passion for Islam”