It was appropriate that the 50,000 delegates at the world’s biggest annual climate change conference should this year descend on the Brazilian city of Belem near the Amazon rainforest, which is often described as “the world’s lungs”. By absorbing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen, the Amazon plays a crucial role in regulating global climate and weather patterns. Home to astonishing biodiversity, the Earth would struggle to balance its atmosphere without it.

The proximity of the world’s largest land carbon sink may have focused minds at the 30th Conference of the Parties (COP), held from 6-21 November. Those with long memories remember Brazil’s crucial role in a forerunner more than 30 years ago, when the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (or ‘Earth Summit’) held in Rio de Janeiro established the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Three decades later, did COP30 deliver for the planet? Brazilian President Lula da Silva called it the “conference of truth”. Others called it the “conference of implementation”. The subtext was clear: there has been too much talk about climate change action in recent years and not enough follow up. Yet agreeing on a concrete plan of action is always tricky when seeking consensus among so many co-signatories. Unfortunately, the only consensus after COP30 was that it failed to deliver.

Lack of buy-in

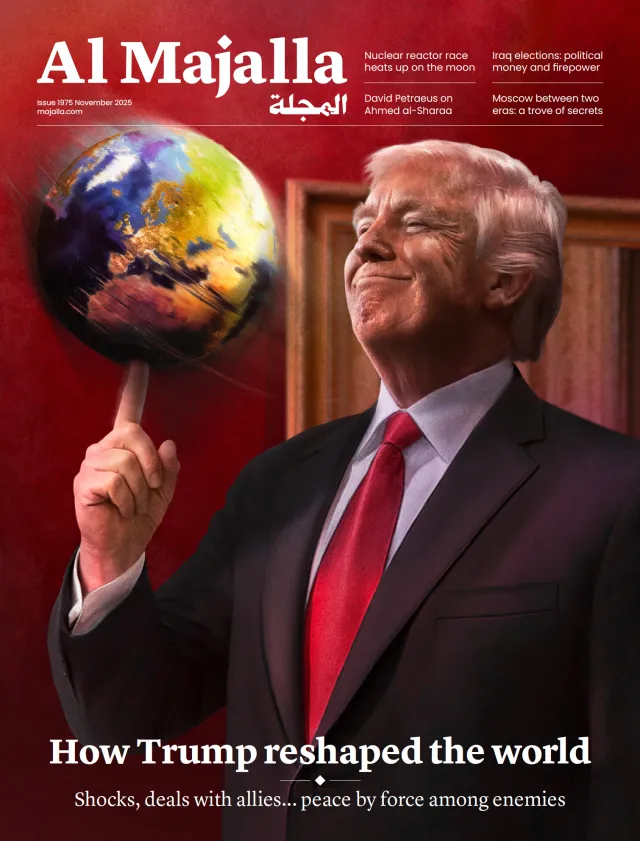

Perhaps COP30 was always likely to be hamstrung, given that the leaders of the world’s three biggest polluters—the US, China, and India—did not attend. China sent a vice-premier, while India sent its environment minister. No senior member of US President Donald Trump’s White House came. Trump withdrew from the Paris Agreement in January, calling climate change “the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world.”

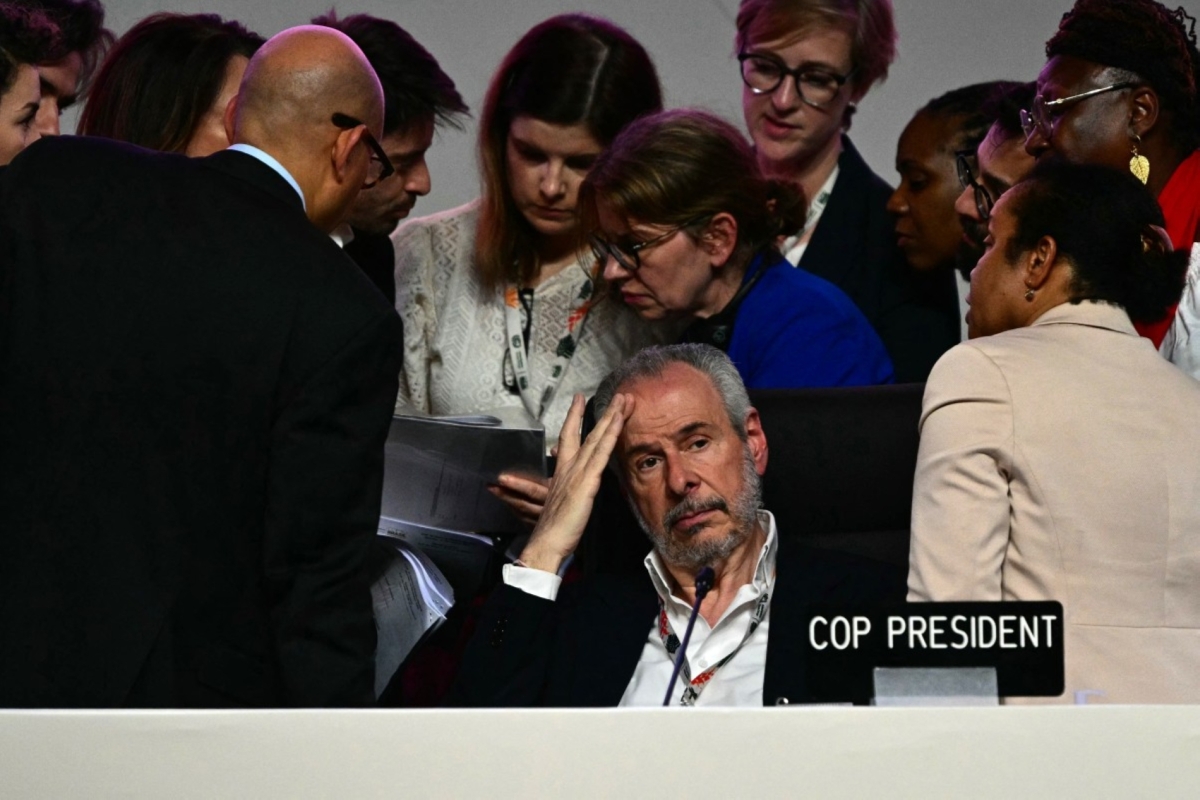

One of the topics that COP30 was supposed to tackle was a roadmap away from fossil fuels, and Lula focused on this in his talks with world leaders ahead of the conference, but André Aranha Corrêa do Lago, a veteran Brazilian climate diplomat who led COP30, sought consensus solutions that eventually meant that no real progress was made. He evoked a sense of mutirão (sense of unity) from the indigenous Tupi-Guarani language, but the resulting text disappointed those hoping to see real change. It made no mention of fossil fuels and omitted a roadmap backed by 90 countries to combat deforestation.

A conference in Colombia was scheduled for April 2026, but, given that it will take place outside the formal COP process, it is unclear whether any outcomes will be legally binding. As a result, the only clear action taken on fossil fuels at COP30 was a decision to discuss it further.

Revising targets

Since the Paris Conference of 2015, participating states have been developing their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and presenting them every five years, so COP30 was a time for NDC revision. Those targets, originally set a decade ago, allowed average temperatures to rise by more than three degrees Celsius (°C). This was revised in 2021 to 2.8 °C, which is still considerably higher than the ambitious 1.5 °C target of the Paris Agreement.

According to the UN, revised NDCs submitted so far would only cut greenhouse gas emissions by 10% by 2035, but the world would need a 60% cut to make 1.5 °C a realistic target. China’s revised NDC gave no specific reduction value, saying instead that levels in 2035 would be 7-10% lower than their “peak value”. Indonesia’s submission suggested progress until 2030, but that this would then plateau until 2035.